Due to marijuana’s supposed low addiction potential, a perceived lack of long-term irreversible side effects, and various social dynamics normalizing it after the War on Drugs changed to a movement towards legalization, marijuana is frequently seen as a less harmful option for drug experimentation in college. In 2018, 44% of high school seniors in Washington state thought there was little to no harm in consistent marijuana usage, and this attitude extends to college students [1]. About 43% of 18 to 25-year-olds in Washington use marijuana recreationally, and 6% use it every day [2]. At some levels of use, marijuana can be more helpful than harmful, especially in the context of anxiety and depression. However, it is easy to underestimate the issues caused by consistent use over time. College students who smoke marijuana are more likely to drop out and have lower GPAs than their classmates who do not use the drug [3]. Additionally, if people in the 18 to 25-year-old range smoke enough to create psychological dependence, they are more susceptible to developing Cannabis Use Disorder than older age groups as they continue to use the drug [4]. Marijuana is extremely difficult to quit if it has formed a habit, due to the various mental effects it produces in those who use it frequently. The brain is greatly impacted, positively and negatively, by marijuana use at any level. Positively speaking, cannabis has strong anti-anxiety effects, reduces chronic pain, and can improve appetite. Negatively, however, cannabis can impact brain structure and capacity, especially in developing brains [5-8]. There is a concerning lack of accurate, unbiased knowledge about this drug, fueled by both the continuing war on drugs and the current push for legalization. Research performed during the War on Drugs or the new push towards legalization shows strong biases either against or in support of the use of marijuana, politicizing a medical topic in an area that should not be biased further by policy. Students and young adults should obtain more informative and unbiased evidence about its neurological effects so they can make an informed choice before using marijuana.

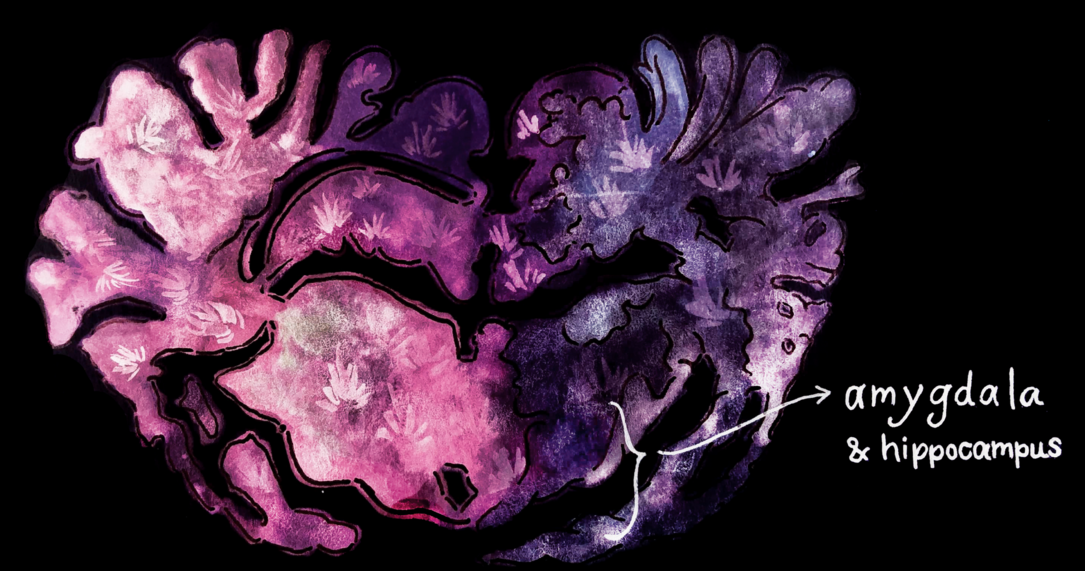

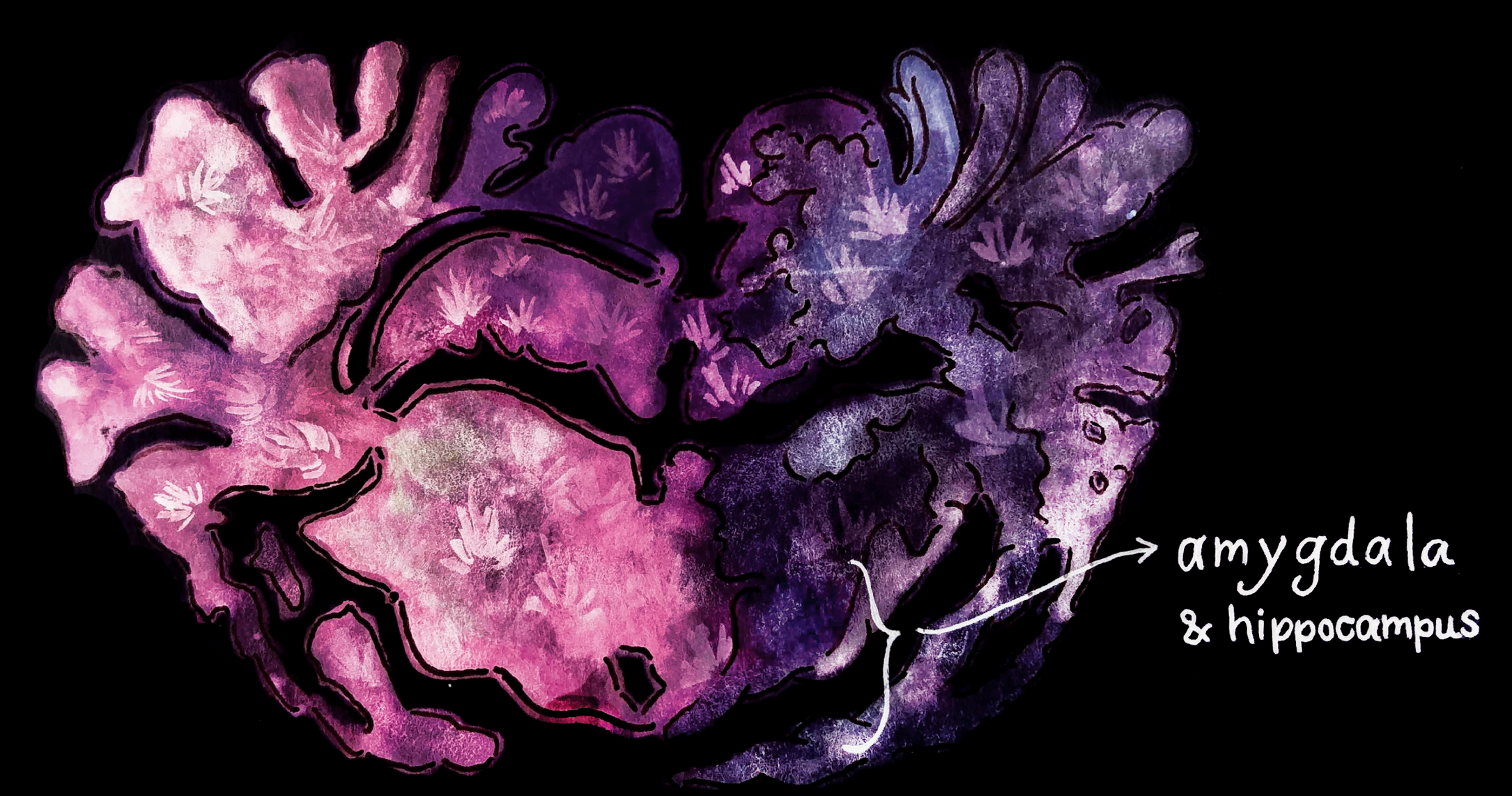

Cannabis has the potential to change some of the major structures and pathways in the brain, especially during development [6-9]. It provokes changes to the gray and white matter throughout the brain that stores cannabinoid receptors, which can decrease the ability of different parts of the brain to communicate with each other. Marijuana can also change brain structures like the amygdala and hippocampus, which are partially responsible for emotional regulation [6, 7]. Changes to gray matter, including the amygdala and hippocampus, and white matter, including myelin, compromise the brain’s ability to communicate efficiently. Myelin, which is used to facilitate neural activity, can be harmed by interactions with cannabinoids [5]. The potential for harm to brain structures increases when frequency of smoking increases. High use, defined by most studies as over ten days of use per month, can decrease IQ levels and neurocognitive ability, and the brain can only partially regain its previous function after abstinence for over a month [8].

There are also notable psychiatric outcomes associated with marijuana use. As a moderately psychoactive drug, it can trigger or exacerbate hallucinations or cannabis-induced psychosis [9]. Cannabis use increases the risk of developing schizophrenia by two or three times, possibly because of its damaging effects on myelin. The negative effects on brain communication, as well as other structural changes, can cause other mental issues in some cases. In people who smoke frequently, there is an increased risk of mental health problems such as depression or anxiety both short-term, in weeks, and long-term, in years [11, 12]. In some studies, marijuana exacerbated feeling of anxiety and depression, while in others it relieved those symptoms.

For many people, marijuana is a powerful anxiety and depression reliever [11]. Anti-anxiety outcomes have been studied fairly frequently, and in cases of low to moderate use (defined as less than ten times a month) marijuana eases these problems without increasing overall anxiety. Certain strains of marijuana, or variants that contain different levels of the two major active components, CBD and THC, have been shown to work differently: oral CBD, or cannabidiol, can reduce anxiety and does not produce a “high,” while oral THC, or tetrahydrocannabinol, has the potential to reduce stress caused by changes in social standings, and does produce a high [4]. When used more than about ten times a month, long-term anxiety increases generally outweigh short-term stress relief. Different strains of marijuana impact different problems. A study of a self-selected cohort of medical cannabis users was designed to test whether marijuana relieved or exacerbated anxiety and depression, and if the strain of marijuana impacted its effects. Participants smoked strains with low THC and high CBD, or high THC and high CBD after self-reporting feelings of anxiety, depression, and stress. The study found that anxiety and stress were helped best by high THC and CBD strains. Women reported a greater decrease in stress and anxiety levels from marijuana. It also found that smoking low THC, high CBD cannabis worked best to reduce feelings of depression but that using marijuana consistently for depression management eventually worsened depression over time [12]. Using cannabis as a treatment for mental issues should always be discussed with a doctor, as it is not right for everyone and there is a difference in strains and potencies between medical and recreational marijuana.

Cannabis products are also useful for chronic pain management, and are undeniably associated with better outcomes than opiates in the vast majority of cases [13]. A study of Medicare Part D patients found that states with medical marijuana prescribed about 1.79 million fewer doses of opiates between 2010 and 2015, with hydrocodone and morphine prescriptions decreasing the most. Marijuana use is a significant advance in pain management, as exposure to opiates in a medical setting is often a gateway to addiction [13]. On that front, the advance of legal marijuana is helpful for managing pain in vulnerable populations, including college students who may not want to take the risk of using opiates for pain.

Knowing all these factors, it is hard to understand exactly how marijuana will affect an individual in the long term, or during a single use. College-age populations especially lack holistic understanding of marijuana, with much of the information released in recent years supporting its more positive effects. Users in college tend to believe that a vast majority of their peers smoke, when about 53% have not in the last year [2]. There is also a lack of information about cognitive effects. A large percentage of users believe that there is little to no short- or long-term risk associated with consistent use, when that is not true. Another misconception is that any negative effects will be solved by abstaining for a period of time, when evidence shows that brain structures can be permanently altered by cannabinoids [6]. Although marijuana has lower addiction potential than “harder” drugs, and less immediate negative effects, it is psychologically habit-forming, which can be a concerning long-term outcome of use [4].

To improve the issue of misinformation about the effects of marijuana use in youth, there must be better explanations of its potential to change brain structures and its links to mental disorders. This information should be shared in classrooms and doctor’s offices, and based in science rather than scare tactics. Treatment systems and support groups to aid in cannabis abuse recovery should be implemented in communities with high rates of use, so people can make social connections that do not depend on marijuana. There needs to be more studies of the long-term physical, emotional, and mental effects of the drug, covering topics such as lung and heart disease, cognition speed, or neurodegenerative diseases. Previous studies have focused on oral intake of the drug but must begin to incorporate smoking as a method of intake. Cannabis has the potential to help many people with a variety of health concerns, and it should be taken and managed as responsibly as possible. This includes the ability to make well-informed decisions about how much and what to smoke.

References

1. Washington State Department of Health. (2018). Marijuana Use for Washington State,

Grade 12. [Data file and factsheet]. Retrieved from http://www.askhys.net/FactSheets.

2. Center for Study of Health and Risk Behaviors at the University of Washington, in

collaboration with the Department of Social and Health Services and the Washington

State Epidemiological Outcomes Workgroup. (2015). Young Adult Health Survey |

MARIJUANA. [Factsheet]. Retrieved from

https://adai.washington.edu/marijuana/research.htm.

3. Arria, A. M., Caldeira, K. M., Bugbee, B. A., Vincent, K. B., & O'Grady, K. E. (2015). The

academic consequences of marijuana use during college. Psychology of addictive

behaviors : journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors, 29(3),

564–575. doi:10.1037/adb0000108

4. Weinberger, Pacek, Wall, Zvolensky, Copeland, Galea, . . . Goodwin. (2018). Trends in

cannabis use disorder by cigarette smoking status in the United States, 2002–2016.

Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 191, 45-51.

5. Cancilliere, M., Yusufov, M., & Weyandt, L. (2018). Effects of Co-occurring marijuana

use and anxiety on brain structure and functioning: A systematic review of adolescent

studies. Journal of Adolescence, 65, 177.

6. Gilman, Jm, Kuster, Jk, Lee, S, Lee, Mj, Kim, Bw, Makris, N, . . . Breiter, HC. (2014).

Cannabis Use Is Quantitatively Associated with Nucleus Accumbens and Amygdala

Abnormalities in Young Adult Recreational Users. Journal Of Neuroscience, 34(16),

5529-5538.

7. Carey, Susan E., Nestor, Liam, Jones, Jennifer, Garavan, Hugh, & Hester, Robert.

(2015). Impaired learning from errors in cannabis users: Dorsal anterior cingulate cortex

and hippocampus hypoactivity. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 155, 175.

8. Mandelbaum, D. E., & De la Monte, S. M. (2017). Adverse Structural and Functional

Effects of Marijuana on the Brain: Evidence Reviewed. Pediatric Neurology, 66, 12-20.

9. Dager, A., Tice, M., Book, G., Tennen, H., Raskin, S., Austad, C., . . . Pearlson, G.

(2018). Relationship between fMRI response during a nonverbal memory task and

marijuana use in college students. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 188, 71-78.

10. Shakoor, S., Zavos, H., Mcguire, P., Cardno, A., Freeman, D., & Ronald, A. (2015).

Psychotic experiences are linked to cannabis use in adolescents in the community

because of common underlying environmental risk factors. Psychiatry Research, 227(2-

3), 144-151.

11. Grunberg, V., Cordova, K., Bidwell, L., Ito, T., Petry, Nancy M., & Winters, Ken C.

(2015). Can Marijuana Make It Better? Prospective Effects of Marijuana and

Temperament on Risk for Anxiety and Depression. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors,

29(3), 590-602.

12. Cuttler, Spradlin, & Mclaughlin. (2018). A naturalistic examination of the perceived

effects of cannabis on negative affect. Journal of Affective Disorders, 235, 198-205

13. Bradford, Ashley C, Bradford, W. David, Abraham, Amanda, & Bagwell Adams, Grace.

(2018). Association Between US State Medical Cannabis Laws and Opioid Prescribing

in the Medicare Part D Population. JAMA Internal Medicine, 178(5), 667-672.