Introduction

Macbeth, Black Swan, and the centuries of art in between serve as a testimony: humanity’s fascination with psychosis is a long-lasting one. Behind the craft, however, lies a wildly misunderstood and misrepresented mental disorder. Psychosis is most frequently characterized by an onset of delusions, hallucinations, and loss of contact with reality. Because it is more often classified as a symptom than as a disorder, most of the 210 million people who experience psychosis worldwide also suffer from a variety of root health defects like schizophrenia, post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and epilepsy [1]. While researchers can thus study the pathology of the disease from several different angles, psychosis in all of its variations comes at the cost of a one-size-fits- all treatment plan. Since psychosis can affect patients in distinct ways depending on the cause of their condition, there is a pertinent need for more individualized treatment options. As an entire body of science works to comprehend and treat psychosis in all of its variations, a hopeful path toward relieving the burden of the condition has emerged within a novel but promising realm: virtual reality.

Virtual reality (VR)is an artificial, immersive, and as the name suggests, virtual experience. Instructions are simple: Put on a headset, complete with specialized goggles and a surround-sound audio system, and enter a three-dimensional, computer-generated, interactive domain. VR’s genius exists in its capacity to map exchanges between patients and personally designed environments. In a clinical setting, this carefully tailored experience allows medical researchers to understand not only how psychosis patients experience the world, but how to best help them. In order to fully conceptualize the scientific community’s utilization and application of VR to treat psychosis, we must first understand the nature of the condition itself.

What We Know About Psychosis

The methodical, rigorous research on the psychopathology of psychosis is still in relatively early stages, but existing studies crack open a window into the condition’s neural mechanisms. An important aspect of treating psychosis is being aware of its manifestations as a symptom of pre-existing conditions; what we know about psychosis in one condition could provide insight on the nature of psychosis as a symptom of another. In 2007, researchers found an association between episodes of psychosis and temporal lobe epilepsy, a condition identified by seizures that start in one of the brain’s temporal lobes [2]. In particular, epilepsy patients whose left temporal lobe is the source of their seizures seemed to suffer severe psychotic episodes far more frequently than those with right temporal lobe epilepsy [3]. A closer look into this phenomenon revealed that those with left temporal lobe epilepsy were also more likely to suffer from structural damage to the limbic system—an important brain structure involved in regulating behavioral and emotional responses [4]. A subsequent dive into the association between limbic structure damage in epilectic patients and psychosis in other parent conditions found that a significant portion of schizophrenic patients tend to suffer from damage to the limbic system as well, such as decreased amounts of grey matter, the tissue containing most of the brain’s neural bodies, in the structures that constitute the limbic system [5].

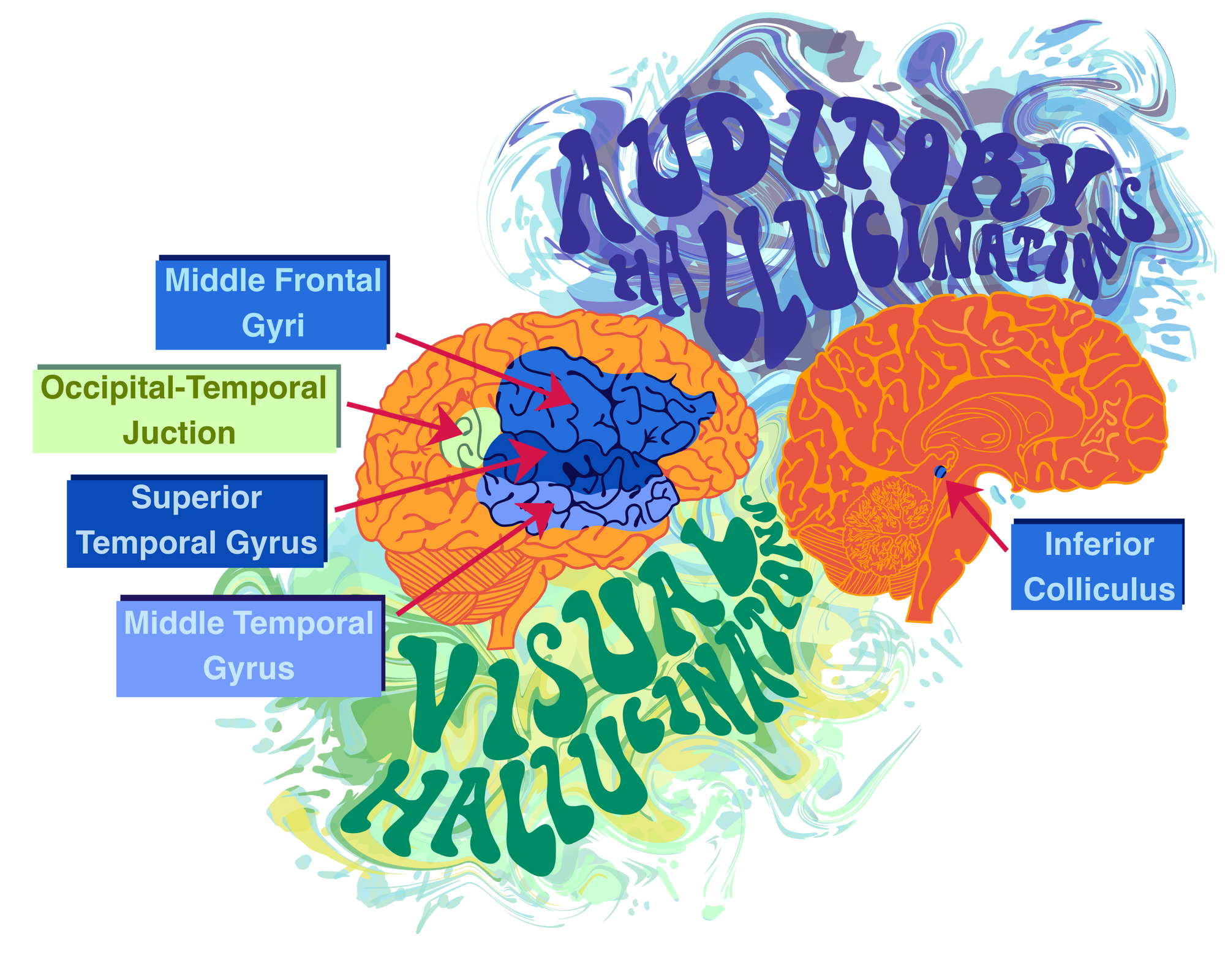

Existing research suggests that when impaired, brain structures that are essential for the effective processing of visual and auditory stimuli are found to be at the root of visual and auditory hallucinationatory symptoms. Auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia patients are marked by a reduction of activity in the left middle temporal gyrus, an area of the brain involved in auditory processing [6]. Interestingly, auditory hallucinations also tend to be the result of impairment to brain structures that are otherwise necessary for producing and understanding human speech [6]. These structures include the inferior colliculus, middle frontal gyri, and superior temporal gyrus [7][8]. Similarly, impairment to brain regions that are necessary for visual processing, like the occipital-temporal junction, often results in visual hallucinations [9].

Understanding the neural and structural workings of psychosis both as a condition and as a symptom is necessary for effective treatment. Existing treatment regimens aim to reshape and regulate neural activity patterns in affected brain areas, primarily those involved in hallucinatory symptoms. Research on how to effectively and safely target major brain structures commonly involved in psychosis—like the limbic structure and the amygdala, a brain area vital in emotional regulation—is still underway.

Existing Treatments

Existing pharmacological treatment options rely primarily on antipsychotic agents. Low level, or entry level, pharma-therapies come in the form of second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), which produce fewer harmful side effects than other existing alternatives [10]. Traditional antipsychotics target a brain area called the prefrontal cortex—a structure subject to decreased levels of white matter material in psychosis patients with schizophrenia [20]. If patients and their physicians find that this treatment isn’t effective, their next best bet is to begin treatment using clozapine. Although it is functional in its purpose as an antipsychotic, clozapine has an alarming caveat; it has been shown to induce a life-threatening decrease in white blood cell count. If clozapine proves to be far too dangerous for the patient, their last existing accessible treatment plan is the controversial electroconvulsive therapy, or ECT [10]. ECT is a form of psychiatric intervention that involves sending brief electrical signals to targeted brain regions with the hope of relieving the symptoms of persistent mental disorders. Despite a significant portion of the scientific community maintaining their stance that ECT is an ethical treatment option, it has been linked with impaired memory post-treatment in the past and remains a strongly debated topic amongst healthcare professionals. [11]

While pharmacological treatments are usually the most accessible and practical options for psychosis patients, they aren’t the only possible sources of relief. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a psycho-social treatment method that includes identifying and redirecting distorted thinking patterns. Recent findings suggest that CBT can be an effective treatment for patients when used in tandem with medications [12]. For instance, the combination of CBT with patients’ usual treatment regimens, has been shown to reduce hyperactivity in the occipital lobes, the areas involved in visual hallucinations, and the thalamus, a crucial component involved in processing the potential threat of facial expressions. [19]. CBT has shown to be especially beneficial when treating mental illnesses like anxiety and depression, but proves to be slightly more challenging in its usage as a form of psychosis treatment. Psychosis is elusive in nature, and can be quite overwhelming for patients who suffer from frequent episodes. Pinpointing relevant thought patterns, triggers, and stressors—an important phase of CBT—can be especially difficult in these cases [13]. Herein lies one of virtual reality’s strongest assets: allowing psychosis patients to identify attributes of, interact with, and navigate their condition in a carefully controlled virtual setting. This gives researchers a closer look into their minds and an angle from which to find a way through the deepest parts of their condition.

Virtual Reality

In 2014, virtual reality systems were made accessible in the consumer market for the first time—VR headsets flew off the shelves and quickly found new homes in the experienced gamer’s must-have collection. As the entertainment industry was adapting to accommodate a myriad of possible VR applications, the medical community wasn’t trailing too far behind. Virtual reality treatment has been primarily used in cases of anxiety-related mental illnesses . Virtual reality in conjunction with CBT for patients with anxiety has been used to identify and redirect harmful thought patterns with high rates of success, primarily because virtual interactions allow for complete control. Therapists can modify specific aspects of the patient’s virtual environment to yield the most effective results while optimizing the pace at which the patient progresses. A patient that finds public speaking anxiety-inducing would be able to walk through a similar virtual experience, identify harmful and debilitating thought patterns, and redirect or neutralize them so that future public speaking encounters don’t pose the same level of mental anguish. Patients who suffer from anxiety tend to respond well to virtual reality CBT interventions, perform well on post-treatment behavioral tests, and report high rates of a decrease in symptoms. As these findings suggest, the precision and personalization of virtual environments are enormous advantages to VR treatment.

VR treatment plans for anxiety have carved out a roadmap on how to proceed with VR treatment for other psychiatric conditions, and yield a promising avenue for the future of psychosis treatment [15]. VR has been used on patients with auditory hallucinations with successful outcomes. In a 2018 pilot study conducted by Percie du Sert and colleagues, patients underwent seven sessions over a 1.5-month period. In one of the beginning sessions, patients created a virtual avatar of their “persecutor”, possessing the face and voice of the source of their most distressing audio hallucination [16]. In following sessions, patients confronted this avatar using a virtual reality system. They were encouraged to be assertive and express themselves honestly when in conversation with their personalized avatar, which became less abrasive and more supportive over the course of the sessions. Clinical assessments were administered after the first and last session, as well as three months post treatment. The results confirmed the researchers’ hypothesis. Three months after the study, patients reported a reduction of verbal hallucinations, a decrease in distress related to verbal hallucinations, and patients’ beliefs about the voices had improved dramatically.

In another high-impact, landmark study, psychosis patients used virtual avatars to practice social skills and navigate their visual and auditory hallucinations in an assertive manner [17]. Park and colleagues asked one group of patients to use VR to interact with randomized virtual avatars, and the other to interact with real people face-to-face, over 10 semi-weekly sessions. Patients interacted with their virtual avatars in familiar situations that were designed to help patients to cope with their social distress, especially in situations when they commonly experience hallucinations and impaired social skills. For example, a patient that finds crowded spaces to be a source of distress would be able to interact with virtual avatars in a computer-generated crowded room. Patients that underwent the VR treatment showed greater social improvement and had more positive feedback regarding their sessions more than the group that did not use VR. The researchers of this study believe that this is because the patients’ virtual interactions were constructed to mirror their specific triggers and previous experiences—but with the added benefit of control. Within their VR situations, patients learn to cope with their emotional reactions and navigate the triggers that give rise to their hallucinations, while still maintaining control of the situation with the help of a licensed psychiatric care professional.

Conclusion

Like any other novel treatment, virtual reality is not without obstacles. VR systems have been shown to induce motion sickness and headaches, and reduce limb control [18]. Some of these side effects might be difficult for patients to handle if their conditions are especially unstable. Because using virtual reality to treat psychosis is essentially uncharted territory, both scientific and civilian communities have expressed several concerns, the most common one being “How do we know that virtual reality is safe to use on psychosis patients?” Thankfully, a study carried out in 2017 gives the concerned public some solace [18]. Virtual scenarios have not been shown to exacerbate or aggravate existing psychotic symptoms. If patients or their physicians worry that virtual reality treatment might dampen the patient’s quality of life, they are welcome to draw back from the treatment plan at any time. Despite its caveats, VR has been shown to be effective because it enables patients to confront their hallucinations and navigate the darkest parts of their condition in the most safe and controlled environments possible.

The scientific community’s hopes for the administration and applicability of virtual reality treatment on a widespread scale are still merely hopes. Researchers are currently most concerned with getting VR treatment plans approved and endorsed such that treatment can eventually be integrated in hospital and outpatient care settings [21]. Each year, researchers carry out dozens of pilot studies exploring the potential of virtual reality psychosis treatments in the hopes that it will one day be accessible to the average patient. A large component of this entails making VR treatments interactive and safe without the guidance of a therapist. Current efforts focus on creating avatar coaches so that those who might not be able to afford consistent therapy sessions can find a way through their condition nonetheless [21]. Despite the challenges VR treatment is bound to face in its path to integration with common therapeutic practices, it offers a glimmer of hope for patients who cannot derive sufficient relief solely from pharmaceutical drugs. Large contributions in funding over the past decade have taken the issue of financial accessibility out of the equation to some capacity, and psychiatric healthcare professionals are confident in virtual reality’s potential as an effective treatment plan/option. At its core, VR is a way forward.

References

- Understanding psychosis. (n.d.). https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/understanding-psychosis/index.shtml.

- Nadkarni, S., Arnedo, V., & Devinsky, O. (2007). Psychosis in epilepsy patients. Epilepsia, 48, 17–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01394.x

- Sachdev, P. (2001). Schizophrenia-Like Psychosis and Epilepsy: The Status of the Relationship. Contemporary Neuropsychiatry, 369–375. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-67897-7_62

- Temporal Lobe Simple and Complex Partial Seizures[1-5]. (2010). Clinical Electrophysiology, 54–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444322972.ch21

- Csernansky, J. G., & Bardgett, M. E. (1998). Limbic-Cortical Neuronal Damage and the Pathophysiology of Schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 24(2), 231–248. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033323

- McGuire, P. K., Silbersweig, D. A., & Frith, C. D. (1996). Functional neuroanatomy of verbal self-monitoring. Schizophrenia Research, 18(2-3), 193. https://doi.org/10.1016/0920-9964(96)85604-0

- Woodruff, P. W. R., Wright, I. C., Bullmore, E. T., Brammer, M., Howard, R. J., Williams, S. C. R., … Murray, R. M. (1997). Auditory Hallucinations and the Temporal Cortical Response to Speech in Schizophrenia: A Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 154(12), 1676–1682. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.154.12.1676

- Shergill, S. S., Brammer, M. J., Williams, S. C., Murray, R. M., & McGuire, P. K. (2000). Mapping Auditory Hallucinations in Schizophrenia Using Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57(11), 1033. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.57.11.1033

- Meppelink, A. M. (2014). Imaging in visual hallucinations. The Neuroscience of Visual Hallucinations, 151–166. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118892794.ch7

- Moore, T. A., & Buchanan, R. W. (2007). The Texas Medication Algorithm Project Antipsychotic Algorithm for Schizophrenia. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 68(11), 1751–1762. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v68n1115

- Previous Ethical Approaches to Electroconvulsive Therapy. (2012). Ethics in Electroconvulsive Therapy, 43–58. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203319833-8

- Ranieri, M. (2015). Pharmacotherapy Casebook: A Patient-Focused Approach, 9th Edition. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, 72(2), 166–166. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajhp/72.2.166

- Turner, D. T., van der Gaag, M., Karyotaki, E., & Cuijpers, P. (2014). Psychological Interventions for Psychosis: A Meta-Analysis of Comparative Outcome Studies. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(5), 523–538. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13081159

- Boeldt, D., McMahon, E., McFaul, M., & Greenleaf, W. (2019). Using Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy to Enhance Treatment of Anxiety Disorders: Identifying Areas of Clinical Adoption and Potential Obstacles. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00773

- Wiederhold, B. K., & Wiederhold, M. D. (n.d.). The Use of Virtual Reality Technology in the Treatment of Anxiety Disorders. Information Technologies in Medicine, Volume II, 19–37. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471206458.ch2

- du Sert, O. P., Potvin, S., Lipp, O., Dellazizzo, L., Laurelli, M., Breton, R., … Dumais, A. (2018). Virtual reality therapy for refractory auditory verbal hallucinations in schizophrenia: A pilot clinical trial. Schizophrenia Research, 197, 176–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2018.02.031

- Park, K.-M., Ku, J., Choi, S.-H., Jang, H.-J., Park, J.-Y., Kim, S. I., & Kim, J.-J. (2011). A virtual reality application in role-plays of social skills training for schizophrenia: A randomized, controlled trial. Psychiatry Research, 189(2), 166–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2011.04.003

- Rus-Calafell, M., Garety, P., Sason, E., Craig, T. J., & Valmaggia, L. R. (2017). Virtual reality in the assessment and treatment of psychosis: a systematic review of its utility, acceptability and effectiveness. Psychological Medicine, 48(3), 362–391. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291717001945

- Kumari, V., Fannon, D., Peters, E. R., Ffytche, D. H., Sumich, A. L., Premkumar, P., Anilkumar, A. P., Andrew, C., Phillips, M. L., Williams, S. C., & Kuipers, E. (2011). Neural changes following cognitive behaviour therapy for psychosis: a longitudinal study. Brain : a journal of neurology, 134(Pt 8), 2396–2407. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awr154

- Artigas, F. (2010), The prefrontal cortex: a target for antipsychotic drugs. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 121: 11-21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01455.x

- Bisso, E., Signorelli, M. S., Milazzo, M., Maglia, M., Polosa, R., Aguglia, E., & Caponnetto, P. (2020). Immersive Virtual Reality Applications in Schizophrenia Spectrum Therapy: A Systematic Review. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(17), 6111. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176111