The boom of the digital age and social media revolution has been a significant phenomenon in human history. As digital communication continues to become more ubiquitous, social media networks are emerging as platforms for users to share ideas, engage in discussion, and invigorate free speech. Social media has been woven into the fabric of our daily lives and infiltrated modern culture, changing the way we communicate and connect with others. While posting pictures of lattes on Instagram and laughing behind filters of augmented dog faces on Snapchat seems innocent enough, prolonged social media use may be indicative of a more insidious nature—that our time and conscious attention are being stolen.

Today, there are entire industries dedicated to capturing and selling attention. Tech giants like Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter have teams writing algorithms carefully designed to exploit psychological vulnerabilities, keeping people as engaged as possible with their content. In fact, social media platforms leverage the very same neural circuitry used by slot machines and alcohol to keep people coming back for more [1]. These circuits allow quick, pleasure-maximizing choices that modulate the perception of pleasure that, if done regularly, can generate the same negative effects found in addictive behavior [2]. Taking a closer look at how creativity disrupts addictive behavior may help us pause before picking up our phones.

Meet Dopamine

Dopamine is responsible for the brain’s reward centers and works very closely with neurochemicals called opioids. The joy felt when eating a delicious frosted donut, having sex, or having successful social interactions is all the work of opioids. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that rewards these types of behaviors that benefit and perpetuate survival [3]. When an action is found to be rewarding, the neurotransmitter is released from an area of the brain called the ventral tegmental area (VTA), the starting point of the mesolimbic dopamine pathway and the principal pathway for the reward system. The stimulated neurons in the VTA project to the nucleus accumbens, known as the “pleasure center,” causing dopamine to flood the area. This mechanism causes the exhibition of a “seeking” behavior—that is, the craving of a certain activity. This causes a desire to repeat the behavior that originally elicited the neural response.

Seeking behavior can be divided into two complementary systems that utilize dopamine in the brain: the “want” and the “like" [4]. The wanting system uses dopamine to propel action from our desires, while the liking system creates temporary feelings of satisfaction. Because tech-focused culture is fast-paced and packed with unique content, users are sustained in the “want” system. The endless stream of opportunities keeps users satisfied but also keeps them in the mode of “seeking" [3].

This chemical relay has been critical for survival from an evolutionary perspective. It is responsible for the motivation needed to navigate through the world, form relationships, and survive. This pathway is also largely why people are intrinsically curious about the world, fueling the search for information and ensuring the discovery of new places to eat and new opportunities for mating [5]. For example, these systems are largely at play in the pursuit of food. A juicy burger eyed from across a restaurant is recognized as a powerful reward that is not only pleasurable but also satisfies a biological need [3]. However, these pleasurable behaviors are not always beneficial. Facebook and Instagram are excellent environments to keep the dopamine reward system hungry for novelty because they promise new experiences, stimulation, and immediate gratification [3]. When this “hard-wiring” is introduced to these types of social media platforms, we can become hooked.

Designed For Addiction

It is not difficult to become digitally duped. Every color, graphic, sound, and feature has been carefully designed and tested to guarantee that eyes stay glued to the screen for as long as possible [6]. In a recent BBC interview, former Mozilla and Jawbone engineer Aza Raskin likened the addictive qualities of social media to “taking behavioral cocaine and just sprinkling it all over your interface” [7].

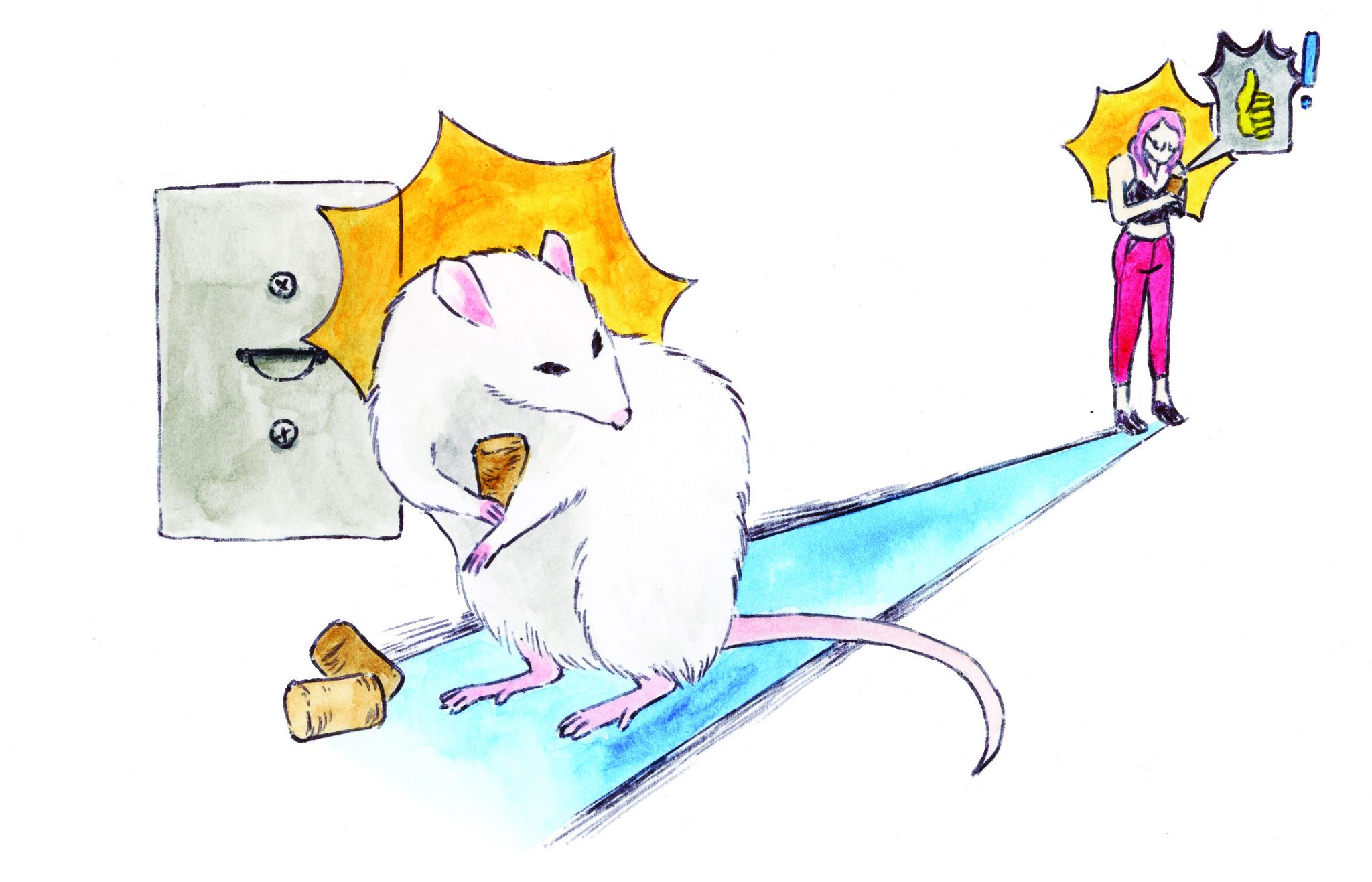

One of the key reasons why social media can be so addictive is that its foundations lie in the premise of operant conditioning [1]. Operant conditioning can best be explained by the Skinner Box, a famous experiment in the 1930s in which a rat pressing a lever was rewarded with the delivery of a food pellet. The reward reinforced the behavior of lever pressing, conditioning the rat to repeat the behavior. Social media works similarly in that each “like” or response to a post acts as a reward. Social media users are driven to repeat these actions of posting, thus initiating the “want” system of the dopamine loop. There is a momentary feeling of satisfaction after posting on social media due to the immediate feedback of peers. However, when the “likes” and comments stop flowing in, this short-lived satisfaction dwindles, and we are soon on the quest for another surge of dopamine.

Pavlovian cues are also woven into our media experience. Smartphone addiction is mediated by the grasp of intermittent reinforcement schedules of social rewards [6]. Justin Rosenstein, creator of the Facebook like button, says “the vast majority of push notifications are just distractions that pull us out of the moment…They get us hooked on pulling our phones out and getting lost in a quick hit of information" [7]. The dopamine response system is especially sensitive to the chimes and vibrations of our phones, and by responding, we reinforce the association of sound and satisfaction [6]. We may not salivate at these short cues, but our brains are absolutely responding to every buzz, ding, and bell we hear.

How Does Social Media Come Into Play?

Social interactions are no doubt important for mental health; humans have an innate drive to affiliate with others, obtain social acceptance, and are naturally curious about others’ lives. Social media provides a convenient environment to not only satisfy social requirements and groom reputations but also explore the lives of others—sometimes on a more intimate level.

People use social networking sites to fulfill the need to belong while satisfying the need to self-present by connecting socially with and appealing to others [5]. These needs have been around much longer than we have been sending selfies and Snapchats. Connecting with others is beneficial to human survival, while upholding a reputation ensures that a connection to a social group stays in place. Social media platforms like Instagram provide a place for people to satisfy these fundamental social drives. For example, users upload photos, and other users provide feedback by commenting or liking as a signal of approval. In theory, this kind of engagement provides reciprocal validation and strengthens social bonds [5]. However, in today’s culture of attention-harvesting, the pre-existing social drives for social recognition might serve as a target for companies that value conscious attention as a commodity. Aza Raskin says he and many software designers are driven to create addictive app features by the business models of the big companies that employed them. In his BBC interview he explained that “in order to get the next round of funding, in order to get your stock price up, the amount of time that people spend on your app has to go up” [7].

Social drives can be broken down further into three areas: social cognition, self-referential cognition, and social reward processing [5]. Social cognition can be defined as any cognitive process that involves other people [8]. When uploading a carefully curated selfie with all the right filters and angles, you may think about how followers or friends will respond. Will they think you look silly or will they shower you with praise? We provide feedback to other users’ posts with a like or a comment while also thinking about their reasoning behind such posts. This process is called “mentalizing”—thinking about the motivations and mental states of others online [5].

Jumping online to share thoughts and ideas also elicits self-referential thought, which is the processing of information relating to oneself [9]. Most people use social media to share all sorts of information about themselves: they post pictures from extravagant vacations and events, discuss ideas, and project personal beliefs onto others [5]. Social networking sites have provided an easily accessible avenue for users to engage in these kinds of self-referential activities. Conversations and feedback provoke us to think about how we are perceived in the world and how one’s own behavior and attitudes size up against others’.

Lastly, social reward processes are constantly being pandered to in the world of digital distraction. Tweets, posts, likes, and friend requests provide an abundant supply of social rewards. Sharing information with others and receiving positive social feedback are considered prosocial behaviors, which activate the pleasure center [10]. Scrolling through someone’s social media profile also stimulates areas in the brain associated with reward. Obtaining new information about a person elicits curiosity, a feeling associated with the activation of the ventral striatum, which includes the nucleus accumbens. These types of positive reinforcement become even stronger when triggered by a minimalistic cue. Even the smallest programmed feature, such as a simple like, can fire up a dopamine response and activate the reward system. This response leaves us momentarily satisfied until we start the dangerous loop of dopamine seeking [10].

Scrolling Our Way to Stress, Sadness, and Anxiety

Although it is natural to want to connect via social media, it may be doing more harm than most people realize. The habit of excessive scrolling and tapping exhibits symptoms similar to those shown in cocaine and gambling addicts [11]. Like a slot machine, the rush of a new notification releases the same flood of dopamine to the pleasure center and tricks the brain into feeling a false sense of fulfillment [6].

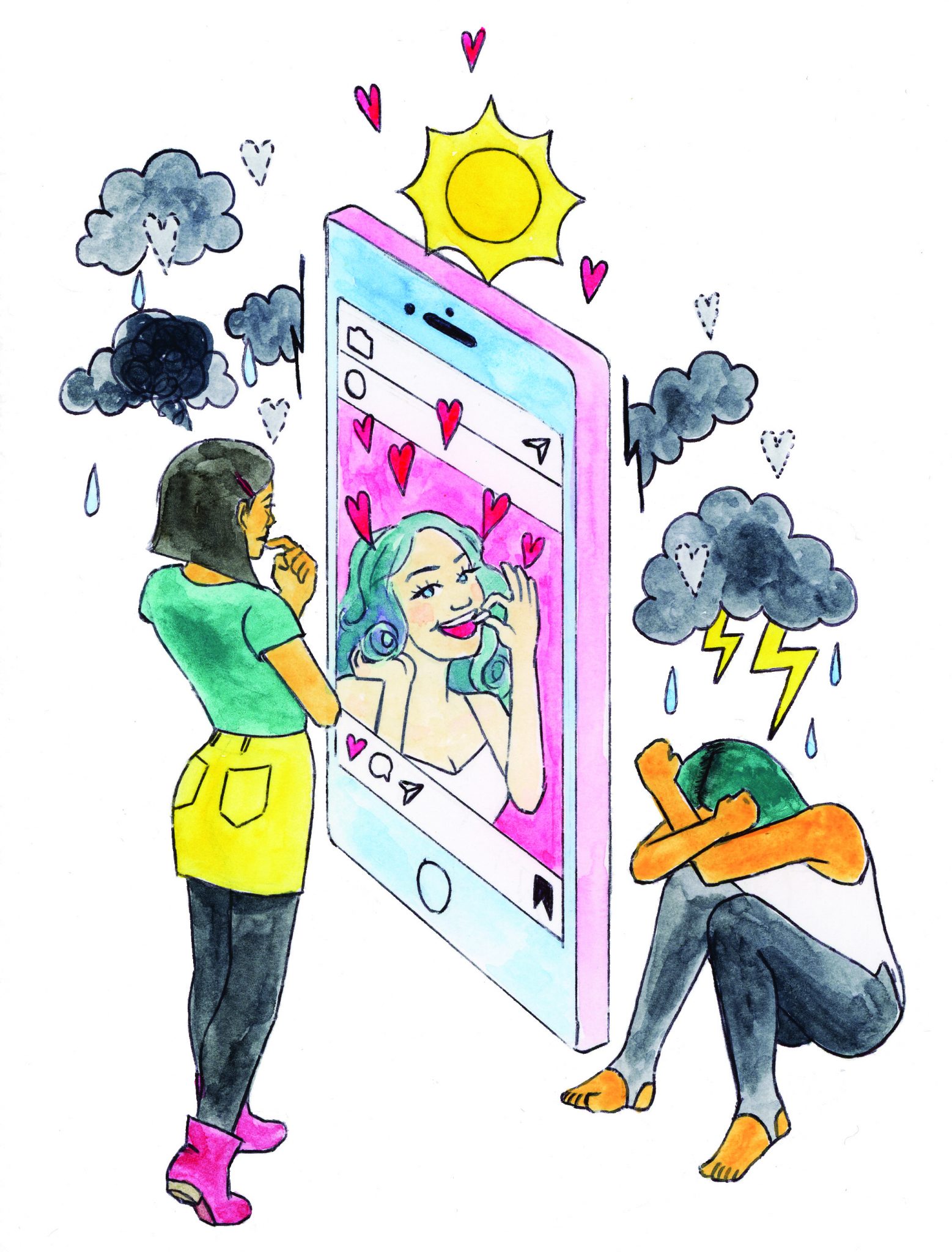

Social media sites like Facebook have been shown to dampen mood and elicit feelings of having wasted time [12]. A 2014 study stated that watching other people’s “highlight reels,” such as vacation photos or posts about others’ successes, evokes feelings of envy, causing a decrease in life satisfaction. Passively consuming this type of social information can have negative outcomes for some users and is associated with feelings of loneliness and decreased social capital [12][13].

Just like substance-related addictions, excessive social media use presents with classic addiction symptoms such as mood modification, mental preoccupation, increased tolerance, craving the addictive behavior, withdrawal symptoms, and relapse [11]. This is because social interaction online activates the same dopaminergic reward circuits used in drug addiction. The same neural circuitry of the dopamine response mechanism becomes hyper-stimulated and pushed to the point where it interferes with daily tasks [14]. While long-term effects of prolonged social media use have not officially been studied, there are hypotheses stating that long-term effects will mirror those of long-term behavioral addictions that could contribute to anxiety, isolation, and depression [14].

One hypothesis attempting to describe the association between time spent online and depressive symptoms is that online communication can be misinterpreted and lead to the wrong impression of another user [15]. Altered perceptions of the truth may lead to incorrect conclusions about how people really look, their education level, intelligence, and moral integrity. A Utah Valley University study observed 425 undergraduate students after using Facebook. Students reported that they felt that other people were happier and had better lives than they did as well as all sharing the feeling that “life is unfair” [15]. While perceiving others as happier and more successful has not been proven to directly cause depression, it may exacerbate the symptoms of individuals who have depressive or anxious tendencies [16].

Physiological changes have also been recognized in internet users who try to quit their online habits. A 2017 study out of Swansea University confirmed that following cessation of an internet session, people experience not only psychological symptoms of withdrawal but also undergo physiological effects such as increased heart rate, blood pressure, and anxiety [17]. These effects, though small, are similar to symptoms seen in individuals undergoing withdrawal from drug use. This study suggests that, for some, social media addiction could be a real physical condition that warrants further investigation [17].

This research field is moving forward at an increasingly rapid pace as the scientific community’s interest in this potentially harmful addiction continues to grow. For example, Temple University’s Department of Psychology is currently investigating neural correlate mapping of providing “likes” to others on social media [1]. The teams of psychologists are looking at “likes” as a monetary and social reward in the online community and exploring to what extent these “likes” recruit reward circuitry. How do “likes” shape reinforcement learning? What explains activation of reward-related regions in the brain when participants like photos? By examining the neural responses of participants who provide positive feedback to others, researchers are taking the first steps in understanding the neural mechanisms underlying individuals’ prosocial experiences online.

The Arts as an Unlikely Antidote

Although the habit of being plugged in at all times has become the new norm, there are benefits of unplugging occasionally. Ask yourself, “do I feel isolated or unhappy after being online?” If the answer to that question is yes, it might be time to look into a creative solution. There may be a way to mitigate the harmful effects of repeated short-term pleasures and create sustainable, long-term well-being.

Emerging research from the University of London suggests that participating in the arts may be a method of overriding incessant media cravings [18]. Whether through viewing or creating, engaging in something creative neutralizes some of the harmful effects of social media’s immediate, pleasure-seeking stimuli. Watching a musician pluck a pleasing tune on a guitar (offline and in-person) stimulates the same dopamine reward pathway used by addictive substances and activities, but instead of provoking the feeling of “want,” the viewer is left feeling satisfied. When we are connected to an activity we enjoy, we enter a pleasurable state known as “flow.” Flow can be described as the total absorption into one coherent, focused neurocognitive state and has been shown to invoke feelings of contentment, happiness, and most importantly, satisfaction. Flow states generally involve heightened activity of a number of systems, including dopamine, endorphins, and norepinephrine, which contribute to the holistic nature of the state [19]. By entering this state of flow, urges and cravings from an addicted mind can be mitigated by allowing the participant to engage in new avenues of thought related to pleasure. For example, creating personally significant artwork triggers memory and frontal experiential neural systems, which aid in meaning-assignation. The moment of meaning-assignation, also called “mastering” or “understanding” an artwork, can create feelings of pleasure and lead to more sustained happiness [18].

Another advantage of participating in the arts is that it generally lacks the instant gratification that is often experienced with excessive social media use. Painting a portrait or watching a ballet does not induce instant gratification in the way that receiving a “like” on social media does [20]. Instead, these pleasurable and rewarding activities generate personal meaning from steady, low-level stimuli. These low-level stimuli, including shapes and tones, and other features such as symmetry and beauty, trigger attention without overstimulating the mesolimbic pathway [18].

Social media companies will continue to conjure up novel ways to compete for our attention. Understanding the science behind what we consume and being aware of how engineered stimuli affect the brain will hopefully lead us to a more intentional experience online. By creating a conscious digital experience, we can begin to protect our emotional and mental health, and participating in the arts may offer a unique solution to social media addiction. Reclaiming our power in a hyper-stimulated world may be as easy as picking up a paintbrush and as simple as visiting the local theatre for open-mic night. These activities—writing, painting, sculpting, singing, dancing—will help curate a better understanding of what is important to us and “rewrite” our biological responses to pleasure. We need to be empowered by knowledge to be free, and in the battle against social media addiction, creativity is key.

References

- Sherman, L., Hernandez, L., Greenfield, P., & Dapretto, M. (2018). What the brain ‘Likes’: Neural correlates of providing feedback on social media. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience,13 , 699-707. doi:10.1093

- Kuss, D., & Griffiths, M. (2017). Social Networking Sites and Addiction: Ten Lessons Learned. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health,14 (3), 311. doi:10.3390

- Smith, K. S., Berridge, K. C., & Aldridge, J. W. (2011). Disentangling pleasure from incentive salience and learning signals in brain reward circuitry. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,108 (27). doi:10.1073

- Meshi, D., Tamir, D. I., & Heekeren, H. R. (2015). The Emerging Neuroscience of Social Media. Trends in Cognitive Sciences,19 (12), 771-782. doi:10.1016

- Veissière, S. P., & Stendel, M. (2018). Corrigendum: Hypernatural Monitoring: A Social Rehearsal Account of Smartphone Addiction. Frontiers in Psychology,9 . doi:10.3389

- Andersson, H. (2018, July 04). Social media apps are ‘deliberately’ addictive to users. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-44640959

- Morgans, J. (2017, May 19). Your Addiction to Social Media Is No Accident. Retrieved from vice.com/the-secret-ways-social-media-is-built-for-addiction

- Seyfarth, & Cheney. (2015). Social cognition. Animal Behaviour , 103, 191-202.

- Meyer, M. L., & Lieberman, M. D. (2018). Why People Are Always Thinking about Themselves: Medial Prefrontal Cortex Activity during Rest Primes Self-referential Processing. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience,30 (5), 714-721. doi:10.1162

- Fareri, D. S., & Delgado, M. R. (2014). Social Rewards and Social Networks in the Human Brain. The Neuroscientist,20 (4), 387-402. doi:10.1177

- Kuss, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2011). Online Social Networking and Addiction—A Review of the Psychological Literature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health,8 (9), 3528-3552. doi:10.3390

- Steers, M. N., Wickham, R. E., & Acitelli, L. K. (2014). Seeing Everyone Else’s Highlight Reels: How Facebook Usage is Linked to Depressive Symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology,33 (8), 701-731. doi:10.1521

- Sagioglou, C., & Greitemeyer, T. (2014). Facebook’s emotional consequences: Why Facebook causes a decrease in mood and why people still use it. PsycEXTRA Dataset . doi:10.1037

- Kuss, D. J., & Lopez-Fernandez, O. (2016). Internet addiction and problematic Internet use: A systematic review of clinical research. World Journal of Psychiatry,6 (1), 143. doi:10.5498

- Chou, H. G., & Edge, N. (2012). “They Are Happier and Having Better Lives than I Am”: The Impact of Using Facebook on Perceptions of Others Lives. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking,15 (2), 117-121. doi:10.1089

- Pantic, I. (2014). Online Social Networking and Mental Health. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking,17 (10), 652-657. doi:10.1089

- Reed, P., Romano, M., Re, F., Roaro, A., Osborne, L. A., Viganò, C., & Truzoli, R. (2017). Differential physiological changes following internet exposure in higher and lower problematic internet users. Plos One,12 (5). doi:10.1371

- Christensen, J. F. (2017). Pleasure junkies all around! Why it matters and why ‘the arts’ might be the answer: A biopsychological perspective. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences,284 (1854), 20162837. doi:10.1098

- Reiblein, E. (2018). Getting into the flow of happiness. Marine Log, 123(9), 7.

- Christensen JF, Pollick FE, Lambrechts A, Gomila Acta Psychol (Amst). 2016 Jul; 168():91-105.