Introduction

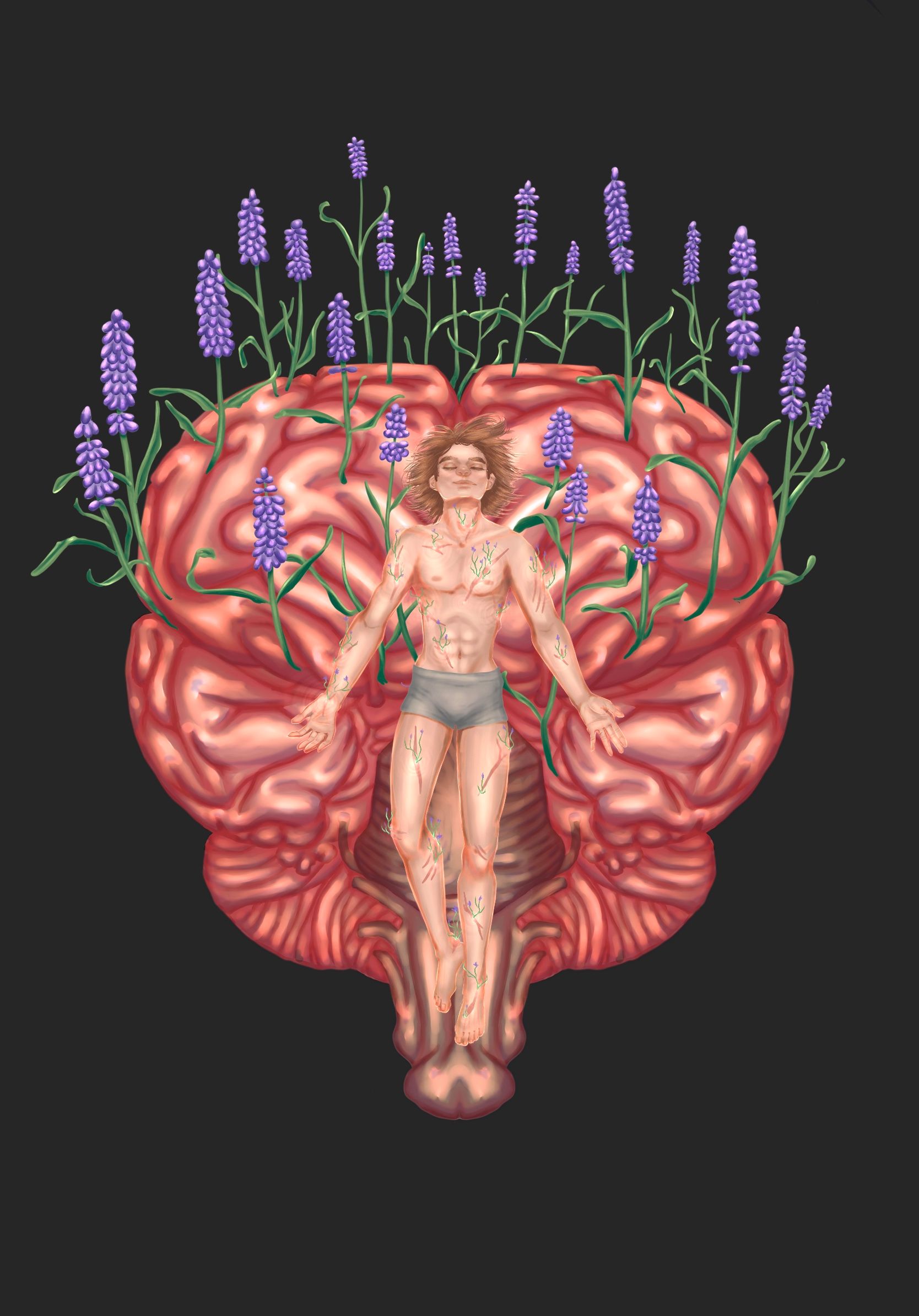

Have your parents ever told you to drink lavender tea to help you destress? Or maybe you’ve looked up cures for a stomach ache and found websites telling you to eat ginger? Turmeric for inflammation, eucalyptus for pain, mint for digestion — the list goes on and on. While a few of these “home remedies” seem questionable at first glance, there is a long history between communities and the plants in their environment, and many herbs that you have heard about can directly affect how you are feeling. This deep-rooted medicinal flora culture is all documented in the field of ethnobotany, the study of how people interact with native plants in their surroundings [1]. There is much to explore about the field’s origin and its use in the realm of neuroscience.

Origin of Ethnobotany

The term “ethnobotany” was first coined when western colonizers in North America began observing how Native American tribes used the plants around them, whether it may have been for food, tools, or medicine [2]. While our primary focus will be on North American indigenous ethnobotany, the use of herbs and shrubs in medicine occurs all over the world — from Ayurvedic treatments in India to palm ethno-medicine in Africa. A spotlight on North America specifically is beneficial as original Native North American ethnobotany in medicine is not adequately represented within modern fields of study [3]. The deaths of most indigenous communities after European colonizers came to America meant that the ethnobotanical cultural practices of the tribes were passed down less frequently or entirely discontinued. Laws or other methods of oppression were put into place preventing Native Americans from participating in their spiritual or healing practices, such as congress paying missionaries $10,000 to suppress Native traditional activities in 1819, or the enactment of the “Indians Appropriation Act” which forced indigenous populations into reservations and away from lands or plants they used for spiritual purposes [4][5]. This drove a deeper wedge between later generations of Native Americans and their traditions — with a large portion of Native Americans unable to pass on their tribal culture [6]. Despite this devastating decline, traces of medicinal ethnobotany and its practices have persisted. Indigenous communities shared a relationship with plants and incorporated them into native cultural ceremonies, spiritual traditions, and healing practices, despite generational and geological gaps between different tribes [7]. Natives used several different treatments specifically for mental troubles; for example, soothing herbs were used as calming agents and certain plants were used to boost mood or memory [8].

Studying these practices may provide some insight into how individual herbs affect our biological processes and help people understand the cultural practices behind Native American ethnobotany. Some modern influences of traditional ethnobotany have emerged in the form of botanical gardens, plant taxonomy, and our focus for the following passages: contemporary medicine [9]. Rosemary and lavender make fine examples of plants that have remained popular and have a strong influence in today's medical society. It's important to gauge a better understanding of these particular herbs because they have demonstrated strong effects in certain mental conditions such as anxiety and neurodegenerative processes through various clinical studies [10][11]. Studying the neurological effects of rosemary and lavender, especially as was used in Native American medicinal ethnobotany, can present potential treatments to help individuals lead healthier lives.

Rosemary

Traditional indigenous tribes' medicine is holistic, focusing on overall physical, spiritual, and mental health, and, as a result, many of their medicinal plants target mental health issues [7]. Rosemary is one such herb that has grown to be quite popular, and has the potential to decrease the rate of neurodegeneration. While this particular plant originated in southern Europe and the western Mediterranean border, it was brought to the Americas and is now used in oils, teas, and perfumes [12]. The Hopi and Tewa tribes, who reside in east Arizona, commonly used the herb as a medicine and source of food [13]. Using modern technology, we are able to understand these tribes’ medicine more clearly and the mechanisms in which rosemary proves to be an effective treatment against neurological problems.

A study conducted by scientists from the VA St. Louis Medical Center determined that rosmarinic acid was the primary compound in rosemary that increases memory function [10]. They used a type of mouse model that experienced accelerated aging and had memory and learning impairments similar to those seen in human dementia cases called Senescence Accelerated Mouse-Prone 8 (SAMP8) to test the effects of rosmarinic acid. The mice were injected with different doses of rosmarinic acid (60% and 10%) and were then tested on their ability to retain information through three tests: a T-maze foot shock, object recognition, and lever pressing. The T-maze foot shock consisted of the rats moving through a maze and encountering certain spots that would shock their feet, while the object recognition test involved the rats differentiating between objects, and the lever press tested if they could identify a lever to press that would elicit a certain response. The mice that received the 60% dose improved in all three tests; they were able to better remember which lever to press, what each object was, and where the foot shocks would occur in the maze more clearly than before. The mice also had lower levels of 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), a molecule responsible for apoptosis (cell death), in the brain cortex and protein carbonyls in the hippocampus. While it is unclear how exactly these two factors contributed to the improvement in memory, one potential explanation for the improvement is that as levels of 4-HNEdecreased, there could have been a lower rate of excessive neuronal death could suggest decreased neurodegeneration [14]. Additionally, the decrease of protein carbonyls, another marker for oxidation in the brain, could indicate that brain deterioration is not progressing as strongly as before. In conclusion, the study's results demonstrated that in controlled doses, rosmarinic acid led to an improvement in memory for mice, which begs the question: Can rosmarinic acid have similar effects on memory in humans?

Scientists at the University of Northumbria investigated rosemary's impacts using a study that tested the effects of rosmarinic acid on human participants to ask if there were any effects of rosemary inhalation on human memory formation [11]. The study consisted of only 144 participants, and steps were taken to increase the reliability of the results. For instance, a blind experiment was conducted in which groups were chosen at random and given a false reason for the study. The subjects did not know which scent they would be smelling, so their reactions would not be swayed by any assumptions. The participants were given rosemary essential oil to inhale, and results were measured using an objective nine point test with cognitive assessments like word and picture recognition, recall accuracy, and spatial memory. Their mood was measured using a visual analogue questionnaire. The study also utilized two control groups, one which did not inhale any aroma at all, and another group who inhaled lavender. In the end, the scientists used the data from the nine point test and questionnaire to conclude that there was not only significantly higher memory performance, but also an improvement in overall mood in those who inhaled rosemary compared to those who inhaled lavender or no aroma at all. The results suggest that rosemary acts as a mood enhancer and has an arousing effect in terms of memory.

Physiologically speaking, rosemary's effect on the brain stems from its ability to break down amino acid chains, which could stop the buildup of toxic proteins that damage memory [15]. The potentially toxic buildup process of amino acids begins with an enzyme called prolyl oligopeptidase (POP), which cleaves specific peptides, such as amyloid beta, which form plaques in people with Alzemier’s disease [16]. When amyloid beta is cleaved, it can leave behind smaller oligomers that form the toxic buildups, while the protein as a whole is not necessarily toxic. The buildup of amyloid beta peptide is suspected to hinder memory formation in the brain and slow down the rate of neurodegeneration. Rosemary contains a compound called rosmarinic acid, which is a non-competitive inhibitor of POP [15]. When rosmarinic acids bind to POP, amyloid beta and other peptides cannot fit into the active site, and their peptide bonds do not get broken. While the mechanisms involved have not been entirely mapped out, this lack of cleaving can be beneficial for the brain in terms of memory development. As a result, POP’s inhibition of amyloid beta cleavage, memory function could improve when rosemary is consumed.

Lavender

The next herb we are focusing on is lavender which is incredibly versatile, frequently found in garnish, teas, and oils. Lavender, much like rosemary, originated from the Western Mediterranean border. It has a reputation for enhancing relaxation and has even been used as a painkiller and a sedative drug [17]. In Native American practices, it was used as a treatment for anxiety and depression by tribes living along the coast of California such as the Shoshoni and Costanoan people [18].

One experiment conducted by researchers from Mohammed V Agdal University measured how mice models reacted to lavender extract [19]. The mice were given four different dosages of lavender orally, and monitored via a traction, fireplace, and hole-board test. In the traction test, the mice were suspended on a wire by its front limbs. If the mice did not make any motions to reach the wire with their unbound back limbs, then they were considered successfully sedated. The reasoning behind this was that any mouse not experiencing chemically induced calmness would try to make an effort to release themselves from suspension. The fireplace test involved placing a mouse into a vertical glass tube, and were regarded to be unusually sedated if they did not try to escape the tube within thirty seconds. Lastly, the hole-board test consisted of placing mice on a board with several small holes in it. The mice’s energy and level of sedation would be measured by the number of times they dipped their head down to explore a hole, with a lower number indicating stronger sedative effects. The results of all three tests revealed that, as the dosage of lavender extract increased, sedative effects became stronger in the mice.

Lavender relieves anxiety by preventing serotonin reuptake [20]. Serotonin is a neurotransmitter that is involved in regulating anxiety, sleep, and happiness. Deficient levels can contribute to anxiety and depression. The commonly proposed solution for these disorders is to find ways to increase the stimulatory signaling effect of serotonin. A compound in lavender called linalool binds to serotonin transporter, a protein involved in serotonin reuptake. By binding to this protein, linalool prevents the serotonin transporter (SERT) from transporting the serotonin back to the presynaptic neuron after it has been released into the synapse. As a result, the postsynaptic neuron continues to receive the signal transmitted by serotonin. Lavender's innate compounds stimulate a continuous feeling of calmness and happiness, which is why they are able to remedy the neurological effects of anxiety and depression.

In addition to inducing relaxation and decreasing pain through preventing serotonin uptake, there is also evidence to suggest that lavender produces these effects by manipulating the neurotransmitter, GABA [21]. GABA is a major inhibitory neurotransmitter for the brain, and helps to counteract the effects of glutamate- a neurotransmitter that is responsible for stimulating neuron firing. Lavender enhances GABAergic pathways, which produces feelings of relaxation and counters pain and anxiety. While the specific compounds in lavender that affect the inhibitory system have not been narrowed down, some potential contributors include coumarin, chalcones, flavanones, and kaempferol derivatives [21]. Future research to narrow down the specific compounds involved in GABA’s system could help create treatments for anxiety derived from lavender.

Cultural Impacts on Public Health and Future Directions

Tribal practices allowed for many breakthroughs in the field of medicine today. The indigenous spiritual healing process combined with their connection to nature led to an overall improvement in physical, mental and emotional health in the Native American population [7]. Many tribes used some of the same herbs for similar purposes- ginger, for instance, was used by the Cherokee, Algonquin, Iroquois, and several other tribes to treat fevers or digestion issues - echoed even in present day home remedies [22]. Certain tribes like the Ojibwe hunted to survive, so they used many herbs to catch prey and learned a lot about the plants around them. Other tribes like the Ho-Chunk relied on the women in their community for foraging, cooking, and the overall health of the family, so they developed knowledge around female reproductive health and collected herbs and plants accordingly [23]. These diverse perspectives and complex use of the surrounding resources greatly influenced the modern medication that we use today. For example, Lithiospermum, a form of oral birth control developed by the Shoshone tribe was based on the knowledge of reproductive systems and health held by the Ho-Chunk and other tribes that allowed for the early precursors [24]. Contrary to harmful misconceptions that indigenous treatments are not as “advanced” as those from other societies, Native American tribes have been using drugs for centuries that are commonly prescribed today like quinine, ipecac, and curare [25]. They also created syringes out of animal bones years before the first official syringe was “invented” in 1853 [26]. This resourcefulness and innovation laid a foundation for further research into medical science, and indigenous knowledge provides herbs that could be used for mental ailments as well as other problems.

Even analyzing a few herbs opens many new inquiries. In the case of rosemary, not only do these studies and their conclusions reveal the herb operates in the brain to improve memory, but it also allows for a potential solution to devastating ailments such as dementia. Studies on the propagation of Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia have yet to definitively name a cause for neurodegeneration. However, many studies suspect that the toxic accumulation of amyloid beta plays a large role. With the potential curing effects of rosemary on these toxic buildups, there may be an interesting avenue of research in which rosmarinic acid is tested in patients with Alzheimer’s disease; if an improvement in memory is shown, then rosemary could be used in a clinical setting as a preventative or gradual treatment, or even in conjunction with existing treatments to slow down dementia.

While the origins of ethnobotany in the United States have been relatively overlooked, there has been a recent increase in studies regarding its implementations into modern medicine today, with ethnobotanical articles increasing over sixfold from 2001 to 2013 [27]. Thanks to this growth, there are many new opportunities for research. It could be worthwhile to test the effects of rosmarinic acid on memory development in patients with dementia. Dementia, a common disease in North America, is caused by accelerated neurodegeneration and rosmarinic acid could counteract that degeneration. Experimenting on the potential differences between a nasal and oral administration of lavender would be interesting as well, since humans also drink tea or inhale essential oils with lavender. Another herb that could be interesting to research is Ashwagandha- used in both Native American ethnobotany treatments and Indian Ayurvedic medicinal practices. The plant holds a lot of potential for treating nerve damage, relieving inflammation, and boosting cognitive function [28]. Finally, it could be worthwhile to decipher which other herbs can actually improve mental conditions and which herbs have no effect whatsoever or induce negative effects in the brain.

This increasing acceptance of traditional medicine has proven to be useful in certain treatments, and common herbs used in tribes have been proliferating in both clinics and pharmacies today. However, there is still the ethical issue of violating protected information from native tribes [29]. If the popularity of “folk” medicine continues to grow in modern medical fields, further consideration needs to be taken regarding the sharing of information from indigenous tribes and acknowledgement of native contributions. Some ways that this can be demonstrated are amplifying indigenous perspectives in medicine and appreciating the roots of our home remedies.

Conclusion

Much can be learned from the ethnobotanical traditions of indigenous tribes, especially regarding advancements in neuroscience. Even though native tribes frequently used herbs such as rosemary and lavender as healing medicines, they are often reduced to simply “home remedies” today, as is often done with ginger, turmeric, chamomile, and countless others. This can give the impression that herbs are not as effective as Western medicine, which is not true. But, by learning about the way these plants affect specific neural mechanisms, we may be able to better understand how important these herbs are and use them to develop effective treatments for neurodegeneration and other mental health disorders. Rosemary, for instance, doesn’t just improve memory through magic or a placebo effect, it contains beneficial compounds such as rosmarinic acid that reduces toxic protein buildup in the brain. Likewise, lavender is commonly used as a bedtime tea or relaxation oil, but not many individuals understand the history or can explain how it facilitates GABA’s inhibitory effects to increase sedative feelings. By learning about how herbal compounds can affect the brain and the native origins and contributions behind these revelations, we can expand on neural treatments to other fields and merge ethnobotanical practices with clinical techniques to improve the modern field of neuroscience.

References

- U.S. Forest Service. Forest Service Shield. (n.d.). Retrieved November 22, 2021, from https://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/ethnobotany/.

- Historiography of north american ethnobotany ⋆ U.S. studies online. U.S. Studies Online. (2015, November 27). Retrieved November 22, 2021, from https://usso.uk/historiography-of-north-american-ethnobotany/.

- Redvers, Nicole, and Be'sha Blondin. “Traditional Indigenous Medicine in North America: A Scoping Review.” PloS One, Public Library of Science, 13 Aug. 2020, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7425891/.

- “Congress Pays Missionaries to 'Civilize' American Indians - Timeline - Native Voices.” U.S. National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, https://www.nlm.nih.gov/nativevoices/timeline/266.html.

- “Congress Creates Reservations to Manage Native Peoples - Timeline - Native Voices.” U.S. National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, https://www.nlm.nih.gov/nativevoices/timeline/317.html.

- National Institutes of Health. (n.d.). American Indian freedom of religion legalized - timeline - native voices. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved November 22, 2021, from https://www.nlm.nih.gov/nativevoices/timeline/545.html.

- Koithan, M., & Farrell, C. (2010, June 1). Indigenous Native American healing traditions. The journal for nurse practitioners : JNP. Retrieved November 22, 2021, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2913884/.

- 23 medicinal plants the Native Americans used on a ... - USDA. (n.d.). Retrieved February 7, 2022, from https://efotg.sc.egov.usda.gov/references/public/GA/23MedicinalPlantstheNativeAmericansUsedonaDailyBasis.pdf

- History of ethnobotany. Society of Ethnobotanists. (n.d.). Retrieved November 22, 2021, from https://societyofethnobotanists.org/history-of-ethnobotany/.

- Farr, S. A., Niehoff, M. L., Ceddia, M. A., Herrlinger, K. A., Lewis, B. J., Feng, S., Welleford, A., Butterfield, D. A., & Morley, J. E. (2016, August 12). Effect of botanical extracts containing carnosic acid or rosmarinic acid on learning and memory in samp8 mice. Physiology & Behavior. Retrieved November 22, 2021, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0031938416306655?via%3Dihub.

- P;, M. M. C. J. W. K. D. (n.d.). Aromas of rosemary and lavender essential oils differentially affect cognition and mood in healthy adults. The International journal of neuroscience. Retrieved November 22, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12690999/.

- Rosmarinus officinalis (rosemary). Rosmarinus officinalis (rosemary). (n.d.). Retrieved November 22, 2021, from https://www.cabi.org/isc/datasheet/47678.

- Native american ethnobotany database. BRIT. (n.d.). Retrieved February 7, 2022, from http://naeb.brit.org/uses/search/?string=rosemary

- G;, P. G. S. R. J. S. W. G. L. (n.d.). 4-hydroxynonenal: A membrane lipid oxidation product of medicinal interest. Medicinal research reviews. Retrieved November 22, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18058921/.

- Ghasemzadeh Rahbardar, M., & Hosseinzadeh, H. (2020, September). Therapeutic effects of rosemary (rosmarinus officinalisL.) and its active constituents on nervous system disorders. Iranian journal of basic medical sciences. Retrieved November 22, 2021, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7491497/.

- Fülöp, V., Böcskei, Z., & Polgár, L. (2001, April 11). Prolyl oligopeptidase: An unusual β-propeller domain regulates proteolysis. Cell. Retrieved November 22, 2021, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0092867400814166.

- Koulivand, P. H., Khaleghi Ghadiri, M., & Gorji, A. (2013). Lavender and the nervous system. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine : eCAM. Retrieved November 22, 2021, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3612440/.

- Native american ethnobotany database. BRIT. (n.d.). Retrieved November 22, 2021, from http://naeb.brit.org/uses/search/?string=lavender.

- Alnamer R;Alaoui K;Bouidida el H;Benjouad A;Cherrah Y; (n.d.). Sedative and hypnotic activities of the methanolic and aqueous extracts of Lavandula officinalis from Morocco. Advances in pharmacological sciences. Retrieved February 7, 2022, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22162677/

- López, V., Nielsen, B., Solas, M., Ramírez, M. J., & Jäger, A. K. (2017, May 19). Exploring pharmacological mechanisms of lavender (lavandula angustifolia) essential oil on central nervous system targets. Frontiers in pharmacology. Retrieved February 7, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5437114/

- Alnamer, R., Alaoui, K., Bouidida, E. H., Benjouad, A., & Cherrah, Y. (2012). Sedative and hypnotic activities of the methanolic and aqueous extracts of Lavandula officinalis from Morocco. Advances in pharmacological sciences. Retrieved November 22, 2021, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3226331/.

- Native american ethnobotany database. BRIT. (n.d.). Retrieved November 22, 2021, from http://naeb.brit.org/uses/search/?string=ginger.

- Ethnobotany of the Ojibwe Indians - NWIC blogs. (n.d.). Retrieved November 22, 2021, from http://blogs.nwic.edu/briansblog/files/2013/02/Ethnobotany-of-the-Ojibwe-Indians.pdf.

- Ogden Publications, I. (n.d.). Natural health. Mother Earth News. Retrieved November 22, 2021, from https://www.motherearthnews.com/natural-health/natural-birth-control-zmaz70mjzkin.

- Virginia McLaurin is a Ph.D. candidate in cultural anthropology at the University of Massachusetts. (2019, March 16). Why the myth of the "savage Indian" persists. SAPIENS. Retrieved November 22, 2021, from https://www.sapiens.org/culture/native-american-stereotypes/.

- Roberts, N. F. (2020, November 29). 7 Native American inventions that revolutionized medicine and Public Health. Forbes. Retrieved November 22, 2021, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/nicolefisher/2020/11/29/7-native-american-inventions-that-revolutionized-medicine-and-public-health/?sh=1bf57a0b1e73.

- Popović Z;Matić R;Bojović S;Stefanović M;Vidaković V; (n.d.). Ethnobotany and herbal medicine in Modern Complementary and Alternative Medicine: An overview of publications in the field of I&C Medicine 2001-2013. Journal of ethnopharmacology. Retrieved November 22, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26807912/.

- Singh, N., Bhalla, M., de Jager, P., & Gilca, M. (2011). An overview on ashwagandha: a Rasayana (rejuvenator) of Ayurveda. African journal of traditional, complementary, and alternative medicines : AJTCAM, 8(5 Suppl), 208–213. https://doi.org/10.4314/ajtcam.v8i5S.9

- Ethnobotany: Challenges and future perspectives. Science Alert. (n.d.). Retrieved November 22, 2021, from https://scialert.net/fulltext/?doi=rjmp.2016.382.387.