It is freshman year and you stand in the middle of a crowded Chi Upsilon Eta fraternity party. Music is pounding in your ears and drunken yells fill the air. In the midst of the stifling pressure and exhilaration, you quickly drink the cheap beer you are holding. It is the start of a routine. For the next four years, you go to Chi Upsilon Eta’s parties every Friday and chug a few beers. Flashforward to senior year. Excitement fills the air as graduation approaches. You decide to stop drinking because you think you have had a good run (and to make your mother happy about your life choices). However, when you go to that last party of the year, the onset of the music and yelling triggers an irresistible urge to drink that flat, yeasty beer. You try to fight it. The more you fight, the more your head hurts, and the more you crave a drink. Moments later, you find yourself chugging that cheap beer…

The above scenario is an example of a stereotypical portrayal of alcoholism. Popular thought insists that drug addiction is an individual problem [1]. This reinforces the atmosphere of mistrust around drug users who need help, not criticism. This is further amplified by sensational, and often conflicting, media reports on who exactly is liable for drug abuse. For many non-experts weighing in on the issue, the blame for the addiction can be shifted solely onto the drug abuser, who lacks the requisite willpower to solve their own issues. However, modern research demands we recognize that the persistence of this condition runs deeper than the individual level. Drug addiction is defined as a chronic, relapsing disorder characterized by compulsive drug seeking, continued use despite harmful consequences, and long-lasting changes in the brain [2]. It is believed that the learning process, in the context of repeated drug use, serves as a gateway for addiction.

Drug use commonly occurs in environments where a person feels most comfortable or at times when a drug is easily accessible. Some people smoke a cigarette in their car every lunch break, or inject heroin at the site where they meet their dealer. Others get their caffeine fix from the coffee at their local cafe every day. Why do we make these sometimes irrational choices, despite knowing the harm they can cause? Studies have found that after continued use, drug-associated cues elicit an anticipatory response to the drug’s biologically significant effects. This mechanism relates to the study of Pavlovian or classical conditioning. Using the Chi Upsilon Eta party scenario, cues (music and yelling) accompanying the primary drug effect are known as conditioned stimuli (CS). The direct signal of the drug (alcohol) is the unconditioned stimulus (US) [3]. The unconditioned response (UR) is the pharmacological effect (drunkenness) that elicits responses that recompense for the biological disturbances induced by the drug [3]. After several pairings of the pre-drug administration CS and pharmacological US, the body develops a drug-compensatory response to counteract the drug’s effect, mediating the development of tolerance [4]. Tolerance is the diminished effect of a drug over the course of repeated usage (e.g., chugging more beer to achieve the same buzz). Withdrawal symptoms are caused by somatic and psychological side effects after cessation of drug use (headache). This is also elicited when the drug cue is present without the drug, precursory to drug-seeking behavior and drug craving. Both tolerance and withdrawal symptoms result from the same conditioned compensatory response in drug taking and signal serious problems characteristic of prolonged drug abuse.

Classical conditioning has likewise been implemented as a potential treatment option to counteract the conditioned effects of chronic substance abuse through Cognitive Behavioral Therapies (CBTs). CBTs commonly approach the issue of drug abuse by exposing the individual to the drug or paraphernalia used. Through repeated exposure, such as the sight or smell of the drug, in the absence of the pharmacological effect of the drug, there is a decrement in the salience of the drug-compensatory response called extinction [3]. In 1993, a study that implemented CBTs in a group of alcohol abusers resulted in a significant increase in the length of maintained alcohol abstinence and a decrease in alcohol volume consumed when drinking [5]. If CBTs could provide a means to help curb drug usage, why is there still such a prevalent problem with drug addiction? In the clinical setting, patients with substance abuse disorders seem to be fully motivated and invested in mitigating their drug use, knowing the adverse long-term consequences that inevitably result from a momentary high. Unfortunately, the abuse continues outside of therapy. Animal studies have shown that extinction to drug taking has occurred in one context, but drug seeking behaviors emerged once again when the context changed [5]. This is because these CBTs previously emphasized focusing on external cues of drug taking, apparent both to the organism experiencing the drug effect and the public’s view of the drug effect [4]. In other words, drug addiction is contingent on another set of cues that can be reinstated in various contexts. These are called interoceptive cues, which are internal, private, and perceivable only to the drug taker [4]. Internal cues for drugs can be divided into self-administration cues and drug onset cues.

Typically, more intense pharmacological effects may occur after engaging in a self-administration ritual. Animals that self-administer drugs, showed more tolerance than the ‘yoked’ animals, which received the same dose independent of their behavior [4]. Furthermore, alcohol-dependent humans portrayed more severe withdrawal symptoms when denied drug access if they self-administered rather than passively received drugs [4]. When a drug is being delivered, people experience the preliminary effects of the drug before feeling the full pharmacological effects of the drug. For example, warmth sensation coming after alcohol may precede the intoxicating effect. Therefore, drug-onset cues can be used as a reliable indicator of the main effect of the drug. Intra-administration association is the association formed within each administration and, like external cues, drug-onset cues influence drug tolerance [4]. Evidently, it was found that rats with a history of administering large doses of morphine displayed behavioral and thermic conditional compensatory responses when small morphine doses were delivered [4]. This supports the theory that self-administration serves as a cue for conditional compensatory response in drug administration for tolerance and withdrawal.

Emotional states and senses preceding drug administration may also serve as reliable cues to conditioned compensatory responses in substance abuse. Some CBTs have been formulated with a focus on developing quasi-cues relating to the emotions that precede drug abuse. In a study on individuals dependent on benzodiazepines (BZs), 76% of participants in the CBT group emphasizing emotional sensations, which focuses on identifying each patient’s high-risk emotions and then helping him or her practice healthy responses, successfully discontinued their use of BZs compared to the 25% of those who only received support and general information [5]. Similarly, such CBT treatment was used on opiate-dependent patients who continued to abuse such substances despite comprehensive therapy including methadone, counseling, and contingency management. The modified CBT found significantly greater reduction in illicit substance abuse (verified by negative urine screens) for women, but not in men. Sex differences in drug addiction may be correlated with negative mood states, which elicit stronger drug-seeking behavior in women than in men [5].

It is evident that Pavlovian conditioning plays a significant and undeniable role in potentiating substance abuse. Not only do external cues influence drug craving and seeking, but interoceptive cues also determine the degree of one’s uncontrolled drug abuse. There is a push for CBTs to recognize and integrate methods that address internal cues of emotional states, self-administration, and drug-onset cues [5][4]. Even with CBTs, drug addiction still proves difficult to combat due to its complexity. It is essential that there be a better understanding of the neurocircuitry and neurobiological mechanisms of drug addiction and learning as they relate to our everyday lives. How are the external and internal cues being generalized in all of the contexts in which drug abusers undergo a continual search for substances of abuse? Current thinking suggests that several signaling molecules (such dopamine and glutamate) regulate drug taking through actions in the mesolimbic system, a region of the brain commonly associated with reward learning [6][ 3]. A study showed replenishment of lost dopamine in the nucleus accumbens, playing a central role in reward, decreases drug taking momentarily for animals that escalated their cocaine intake [6]. This result reveals that even though society is sufficiently equipped to help those addicted to drugs control their intake, there is a long-term brain modification influencing uncontrolled drug use that we have not yet identified. Such findings suggest that we may need to restructure our views on abstinence, which has long been thought as the most effective method of treatment.

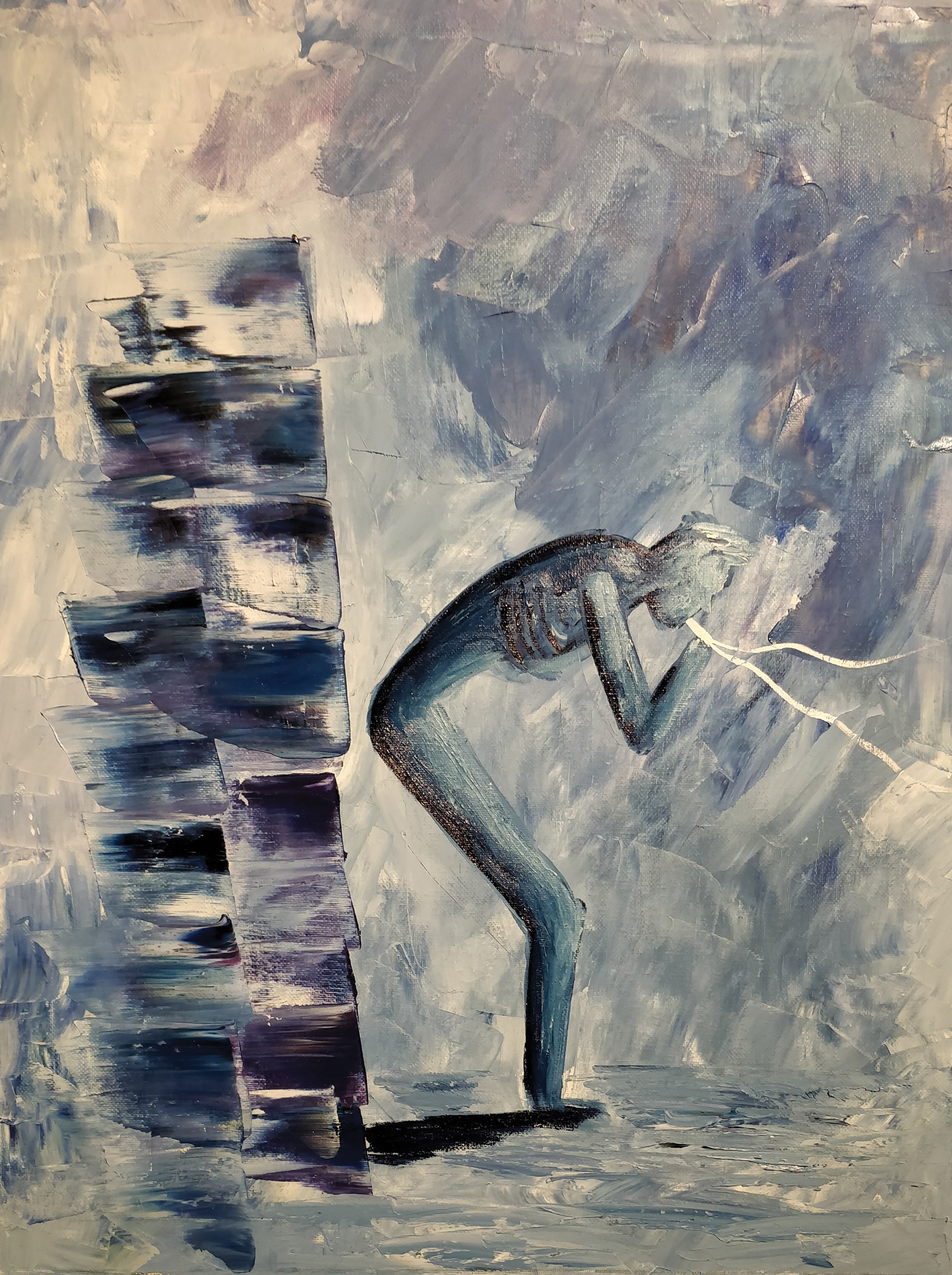

Now more than ever it is crucial that we further investigate drug addiction. It is evident as an unfortunate consequence of the opioid crisis that resulted in 63,000 drug overdose deaths in 2016 alone [7]. It was estimated that at least half of these deaths involved prescription or illicit opioids [7]. The drug crisis developed in part due to inappropriate prescription practices, providing patients with easy access to opioids without a full understanding of the potential for abuse. Peculiar behavior then results, such as hallucinations and actions based on impulse, as evidenced in those with drug addiction [1]. When someone loses that control, it can lead to anxiety and learned helplessness. Care needs to be taken to ensure that the direction of the current discussion does not switch from the extreme of over-treatment to that of under-treatment, but rather evolve to become one that seeks to identify and establish improved treatment practices to the benefit of patients. Punishing drug use without a well-defined understanding of the biochemical mechanisms involved only serves to isolate this vulnerable population, causing needless discrimination and stigma.

References:

1. Hammer, R. R., Dingel, M. J., Ostergren, J. E., Nowakowski, K. E., & Koenig, B. A.

(2012). The experience of addiction as told by the addicted: incorporating biological

understandings into self-story. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry, 36(4), 712-734.

2. NIDA. (2018, July 2). Media Guide. Retrieved from

https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/media-guide on 2019, April 22

3. Perry, C. J., Zbukvic, I., Kim, J. H., & Lawrence, A. J. (2014). Role of cues and contexts

on drug-seeking behaviour. British journal of pharmacology, 171(20), 4636–4672.

doi:10.1111/bph.12735

4. Siegel, S. (2005). Drug Tolerance, Drug Addiction, and Drug Anticipation. Current

Directions in Psychological Science, 14(6), 296–300. doi:10.1111/j.0963-

7214.2005.00384.x

5. Otto, M. W., O' Cleirigh, C. M., & Pollack, M. H. (2007). Attending to emotional cues

for drug abuse: bridging the gap between clinic and home behaviors. Science & practice

perspectives, 3(2), 48–56.

6. Willuhn, I., Burgeno, L. M., Groblewski, P. A., & Phillips, P. E. (2014). Excessive

cocaine use results from decreased phasic dopamine signaling in the striatum. Nature

neuroscience, 17(5), 704–709. doi:10.1038/nn.3694

7. U.S. drug overdose deaths continue to rise; increase fueled by synthetic opioids. (2018,

March 29). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2018/p0329-drug-

overdose-deaths.html

- Hammer, R. R., Dingel, M. J., Ostergren, J. E., Nowakowski, K. E., & Koenig, B. A. (2012). The experience of addiction as told by the addicted: incorporating biological understandings into self-story. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry , 36 (4), 712-734.

- NIDA. (2018, July 2). Media Guide. Retrieved from https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/media-guide on 2019, April 22

- Perry, C. J., Zbukvic, I., Kim, J. H., & Lawrence, A. J. (2014). Role of cues and contexts on drug-seeking behaviour. British journal of pharmacology , 171 (20), 4636–4672. doi:10.1111/bph.12735

- Siegel, S. (2005). Drug Tolerance, Drug Addiction, and Drug Anticipation. Current Directions in Psychological Science , 14 (6), 296–300. doi:10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00384.x

- Otto, M. W., O’ Cleirigh, C. M., & Pollack, M. H. (2007). Attending to emotional cues for drug abuse: bridging the gap between clinic and home behaviors. Science & practice perspectives , 3 (2), 48–56.

- Willuhn, I., Burgeno, L. M., Groblewski, P. A., & Phillips, P. E. (2014). Excessive cocaine use results from decreased phasic dopamine signaling in the striatum. Nature neuroscience , 17 (5), 704–709. doi:10.1038/nn.3694

- U.S. drug overdose deaths continue to rise; increase fueled by synthetic opioids. (2018, March 29). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2018/p0329-drug-overdose-deaths.html