Introduction

Most of us can probably recall the last vivid dream or nightmare that we’ve had. Maybe it was trekking through a futuristic city worlds away, maybe it was running from a monster with a seemingly familiar presence, or perhaps it was simply the terrifying jolt awake from a missed deadline or late assignment. Although in these dreams we see ourselves running, fighting, or moving through places as if we were doing so in reality, our bodies remain paralyzed while we are asleep. Humans undergo two cycles during normal sleep: REM (rapid eye movement) and non-REM. During REM sleep, our bodies remain stationary while we undergo our dreaming period [1]. This is for our own safety, as a lack of bodily regulation can cause injury during sleep, fueled by the intensity of our dreams. However, there are people who suffer from an absence of this inhibition: a neurological disease called REM Sleep Behavior Disorder (RBD).

Occurring in less than one percent of the population, RBD is categorized as a condition in which people physically act out their dreams through sudden, rapid movements or vocalizations during REM sleep [2]. The dreams that induce these reactions are often unpleasant for the individual, and the reactive movements can cause physical harm to themselves as well as others. RBD is most common in adults over 40 years of age — who are already more susceptible to physical injury — which makes this condition especially debilitating [2]. Although this disease affects only a small fraction of the population, research into its peculiar nature has provided insight into the causes of related neurological disorders such as Parkinson's Disease (PD).

Mechanisms & Manifestations

RBD consists of two major components: REM sleep without atonia (RSWA) and dream enactment behavior (DEB) [2]. Atonia is the normal paralysis of muscles during sleep caused by the inhibition of electromyographic tones, or electrical signals generated by muscle activity. This inhibition causes the muscles to weaken, thus preventing the person from having the strength to act out movements associated with their dreams. Patients with RBD lack muscular atonia and therefore are able to perform such movements. Although the exact degree to which the electromyographic activity is considered “normal” or “in-range” during typical REM sleep is yet to be established, increased electromyographic activity is observed in RBD patients compared to healthy subjects [2].

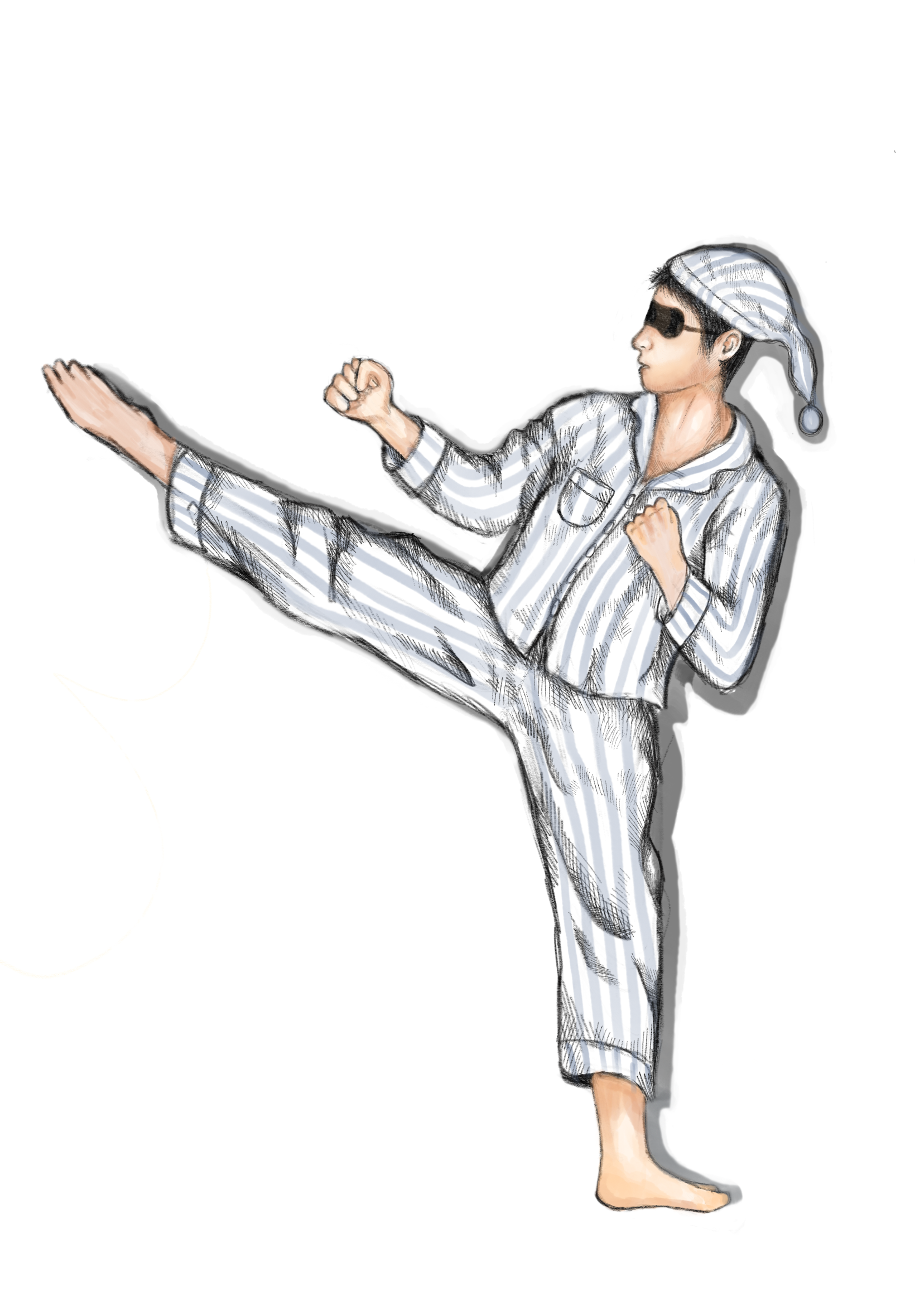

With excessive muscle activity, patients may also experience DEB. This occurs in the form of kicking, flailing around, or sitting up and leaving the bed, among various physically or verbally violent behaviors. After leaving the bed, it is common for a patient to begin running from a presence in their dream, which can be especially dangerous. Patients’ muscles have little-to-no control and can fall prey to involuntary movements, which can injure them or their partners in bed. Since dreams associated with episodes are often unpleasant (such as nightmares), aggressive vocalizations can also occur. Patients are prone to screaming, swearing, and shouting phrases connected to their dream sequence [3]. Although most people tend to forget about their dreams after a day or two, patients with RBD can typically recall the details of dreams associated with their DEB episodes, which then causes them to have further negative association with sleeping [2].

Diagnosis

According to the 2nd edition of the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, four criteria must be met to diagnose RBD [2]. One of these criteria is verifying that the condition cannot be attributed to any other sleep disorders, mental disorders, or use of medications or substances. The occurrence of RSWA is another criterion, as mentioned previously. To measure the degree of RSWA, clinicians conduct a polysomnography, which generates a report known as a polysomnogram (PSG). More commonly known as a sleep study, a PSG measures and records blood oxygen levels, heart rate, brain waves, breathing, and motor activity including leg and eye movements during sleep [4]. Electrodes are attached to a patient's head and limbs to record brain activity and muscle movements, a sensory belt is affixed to measure breathing, and a nasal sensor is used to monitor airflow. In a patient with RBD, a PSG will record frequent sleep vocalizations and complex motor movements — these are noticeably different from the small twitches we normally make during sleep. From this, the PSG will record heightened amounts of electromagnetic activity in the muscles, to effectively pinpoint RSWA [5]. Along with RSWA, the patient must have a history of DEB or other atypical sleep behaviors reported via a PSG.

In addition, no epileptiform activity must be detected by an electroencephalogram (EEG). Epileptiform activity refers to an occurring phenomenon in people with epilepsy indicated by sharp spikes in brain electrical activity. Since this is different from the neuroelectrical activity found in patients with RBD, there must be no epileptiform activity present, or at least a means to distinguish between the two in order for a diagnosis to be made of RBD [2]. This is because although RBD-associated neuroelectrical activity has its minute differences from epileptiform activity, they can still be hard to differentiate with current instruments and techniques.

Interestingly enough, this narrow gap in difference has led RBD to be often confused with seizures by those unfamiliar with the disorder. One case existing in modern science took place during an international commercial flight [2]. A patient with RBD fell asleep during the trip, and at a certain point started punching and kicking the air around them. This was interpreted instead as a seizure, and the pilots changed course back to the American mainland for medical treatment. When all was said and done, thousands of dollars had been spent on unnecessary emergency treatment, and all passengers had to change their travel plans. This is one of the many examples why a substantial lack of knowledge on this particular sleep disorder can cause an even more disruption in people’s lives.

Treatment

When it comes to treating RBD, there are both preventative measures and medical therapies that can be done. Preventative measures include placing a mattress or other soft objects on the sides of beds to minimize injury from the falls, as well as moving sharp and hazardous objects away from the sleeping area. Patients can also use protective barriers to prevent themselves from falling off or exiting the bed.

In addition, patients may also choose drug therapies. Clonazepam, a benzodiazepine, has shown the greatest ability in reducing RBD-related episodes, with common doses of less than one milligram per night [2]. A benzodiazepine is a depressant that is commonly used to treat anxiety-related conditions and seizures [6]. Clonazepam is the most favorable drug in treating RBD simply because compared to other drugs, it is accompanied by the least amount of cognitive decline and chance for possible sleep apnea, the phenomenon of one’s airways closing during sleep [2]. Studies have also found a correlation between the intake of melatonin, a supplement that promotes sleep, (with or without clonazepam) and the reduction of RBD symptoms. Melatonin, compared to Clonazepam, is less likely to react with other drugs, and because RBD patients tend to be elderly, melatonin is preferred to mitigate risk [7].

Besides the fact that treatment greatly reduces the chance of physical bodily harm, there is another reason treatment is important for the individual. It has been commonly shown that in couples where one partner has RBD, a choice frequently made is to sleep in different rooms, which can greatly reduce intimacy and cause strain on a patient's relationship to their partner [2]. This contributes to the disorder’s disruption across much of a patient’s lifestyle, and enforces the idea that treatment for these individuals is crucial and should be readily accessible.

Further Implications & Current Research

RBD has long been linked to and is a common symptom of Parkinson’s Disease, as up to 90.9% of people who have RBD tend to later develop an alpha-synucleinopathy, the class of neurodegenerative diseases which includes PD [8]. In the past, studies have strived to understand the association between RBD and PD. A 2019 study done by researchers in Japan observed the role of alpha-synuclein, a protein responsible for regulating neurotransmitter release, in disrupting REM sleep in mice [9]. Researchers introduced mutations into the zygotes of mice and analyzed their offspring for the occurrence of Parkinson’s-like symptoms and RSWA. They found that mice’s alpha-synuclein genes (SNCA) that were mutated similar to genes found in Parkinson’s disease patients experienced RSWA at just 5 months of age. Researchers also observed a degeneration of neurons that release dopamine in these mice, recapitulating PD symptoms. Overall, the study was able to produce a model of early-onset Parkinson's by simultaneously inducing RBD by modifying the alpha-synuclein gene in mice. The presence of these findings in mice models suggests that similar outcomes to mutations in the SNCA genes of humans can possibly be observed.

Emerging research has also shown linkage between depression and sleep disorders. Sleep abnormalities and disorders are some of the most integral symptoms of depression and serve as potential risk factors for the development of the disorder [10]. Parts of the brain responsible for emotional processing are dependent on normal, healthy sleep-wake regulation. At a molecular level, dysregulation of serotonin and norepinephrine systems (the neurotransmitters responsible for emotional processing) may contribute to REM sleep abnormalities [10]. This hints to the involvement of these neurotransmitter system disturbances possibly having a role in RBD.

Although RBD only affects a small population, this doesn't mean it should be ignored. Even though the mental scenarios that RBD can induce in one’s mind may seem comical, it is extremely important to recognize the pain it can cause in individuals. From physical pain inflicted on themselves and their loved ones at night and the resultant strain on intimacy, to the violent dreams that play through their mind, RBD patients learn to fear the nighttime — the time of day normally reserved for rest and rejuvenation. Treatment by drug therapy and environmental restructuring are key components in providing a better lifestyle for these patients. When left untreated, RBD may lead to risk of developing additional mental illnesses or PD. RBD makes an irrational fear of the dark rational, but every day, there is more research getting patients one step closer to the light at the end of the tunnel.

References

- Dauvilliers, Y., Schenck, C. H., Postuma, R. B., Iranzo, A., Luppi, P. H., Plazzi, G., Montplaisir, J., & Boeve, B. (2018). REM sleep behaviour disorder. Nature reviews. Disease primers, 4(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-018-0016-5

- Boeve B. F. (2010). REM sleep behavior disorder: Updated review of the core features, the REM sleep behavior disorder-neurodegenerative disease association, evolving concepts, controversies, and future directions. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1184, 15–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05115.x

- McCarter, S. J., St Louis, E. K., & Boeve, B. F. (2012). REM sleep behavior disorder and REM sleep without atonia as an early manifestation of degenerative neurological disease. Current neurology and neuroscience reports, 12(2), 182–192. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-012-0253-z

- Rundo, J. V., & Downey, R., 3rd (2019). Polysomnography. Handbook of clinical neurology, 160, 381–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-64032-1.00025-4

- Jiang, H., Huang, J., Shen, Y., Guo, S., Wang, L., Han, C., Liu, L., Ma, K., Xia, Y., Li, J., Xu, X., Xiong, N., & Wang, T. (2017). RBD and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Molecular neurobiology, 54(4), 2997–3006. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-016-9831-4

- Dokkedal-Silva, V., Berro, L. F., Galduróz, J., Tufik, S., & Andersen, M. L. (2019). Clonazepam: Indications, Side Effects, and Potential for Nonmedical Use. Harvard review of psychiatry, 27(5), 279–289. https://doi.org/10.1097/HRP.0000000000000227

- McGrane, I. R., Leung, J. G., St Louis, E. K., & Boeve, B. F. (2015). Melatonin therapy for REM sleep behavior disorder: a critical review of evidence. Sleep medicine, 16(1), 19–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2014.09.011

- St Louis, E. K., & Boeve, B. F. (2017). REM Sleep Behavior Disorder: Diagnosis, Clinical Implications, and Future Directions. Mayo Clinic proceedings, 92(11), 1723–1736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.09.007

- Taguchi, T., Ikuno, M., Hondo, M., Parajuli, L. K., Taguchi, K., Ueda, J., Sawamura, M., Okuda, S., Nakanishi, E., Hara, J., Uemura, N., Hatanaka, Y., Ayaki, T., Matsuzawa, S., Tanaka, M., El-Agnaf, O., Koike, M., Yanagisawa, M., Uemura, M. T., Yamakado, H., … Takahashi, R. (2020). α-Synuclein BAC transgenic mice exhibit RBD-like behaviour and hyposmia: a prodromal Parkinson's disease model. Brain : a journal of neurology, 143(1), 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awz380

- Wang, Y. Q., Li, R., Zhang, M. Q., Zhang, Z., Qu, W. M., & Huang, Z. L. (2015). The Neurobiological Mechanisms and Treatments of REM Sleep Disturbances in Depression. Current neuropharmacology, 13(4), 543–553. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159x13666150310002540