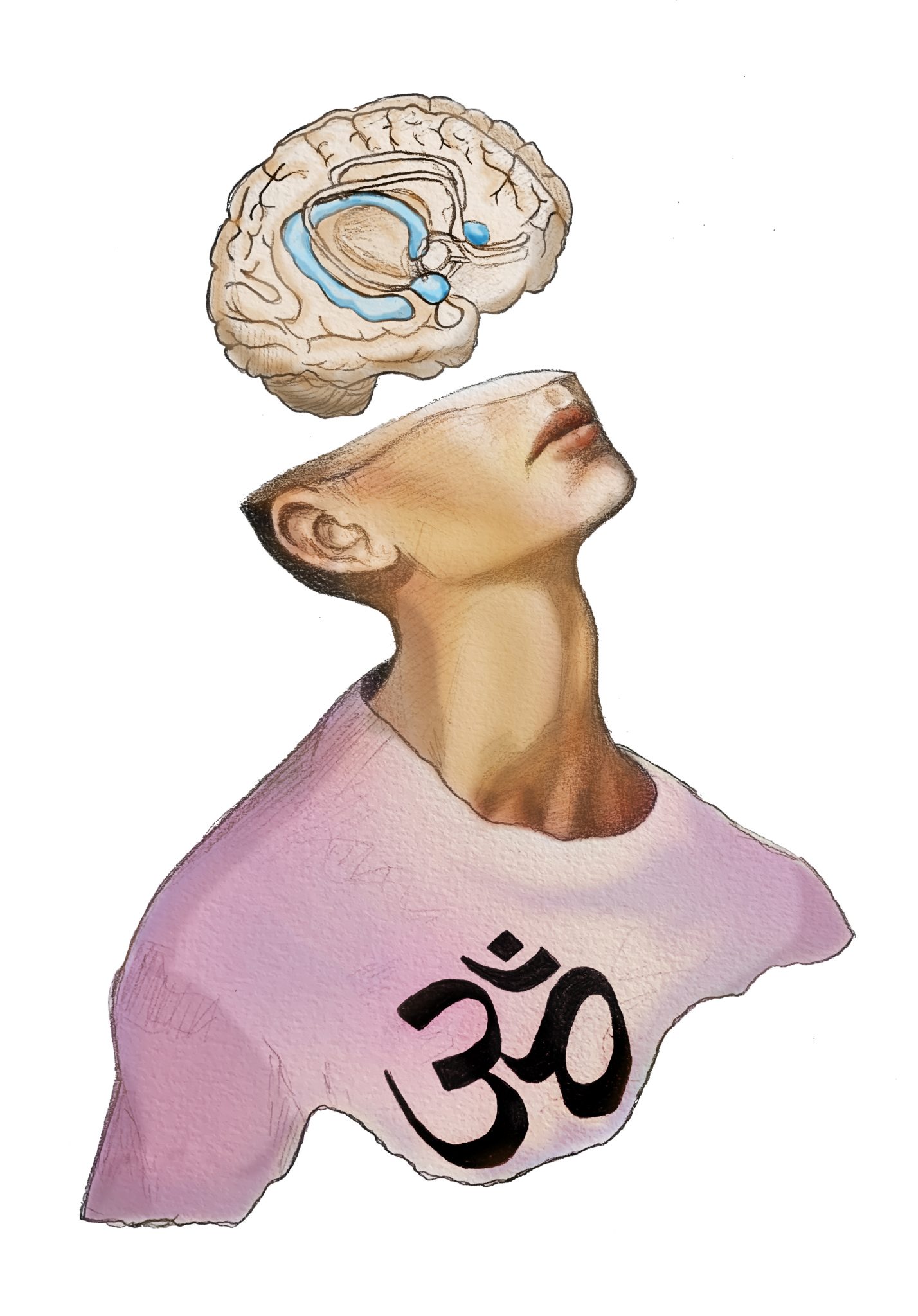

It is impossible to ignore the association that exists in the modern era between meditation and the calming of one’s mind and emotions–the image of a lackadaisical hippie telling one to just breathe might spring to mind. Recently, this association has come to merit a closer look. By 2015 the estimated number of people living with depression worldwide increased to 322 million, according to a 2017 report from the World Health Organization [1]. Depression is a condition characterized by feelings such as persistent sadness, loss of interest, and fatigue that severely alter a person’s disposition. While research on its causes and mechanisms has not provided definitive conclusions, recent studies have looked into meditation as an alternative treatment to depression. These studies, which explore the physiological effects of meditation on the brain, provide a glimmer of hope to those in the throes of depression. However, in order to grasp how meditation might be used to treat mental health, it is essential to understand what the practice of meditation is and how it relates to the neuroanatomy of the depressed brain.

The word meditation has a different definition depending on the context. For example, some may think of active meditation forms such as Kundalini yoga, where movement is the object of focus. Meanwhile, others may think of introspective meditation–where a specific object is chosen within the self and centered on––such as loving-kindness meditation. It is no wonder that it can be difficult to navigate the question of what meditation is. A paper published by scientist Jon Kabat-Zinn provides a more cogent interpretation of meditation [2]. Kabat-Zinn describes meditation as a way of being in which one pays attention to the contents of consciousness in the present moment by focusing on elements such as breath. This notion may surprise individuals, as the media often misrepresents meditation. A common misconception is that meditation is a state in which one relaxes and one’s mind goes completely blank. It is quite the opposite; Kabat-Zinn says one’s mind can be jam-packed with thought, worry, or any other mental state that may arise when going about one’s day. What really constitutes the practice of meditation is the awareness of the objects that may emerge when you close your eyes to meditate, such as thoughts, emotions, and senses. It is this awareness of one’s consciousness in meditation that allows for introspection, relaxation, and development of emotional intelligence [2].

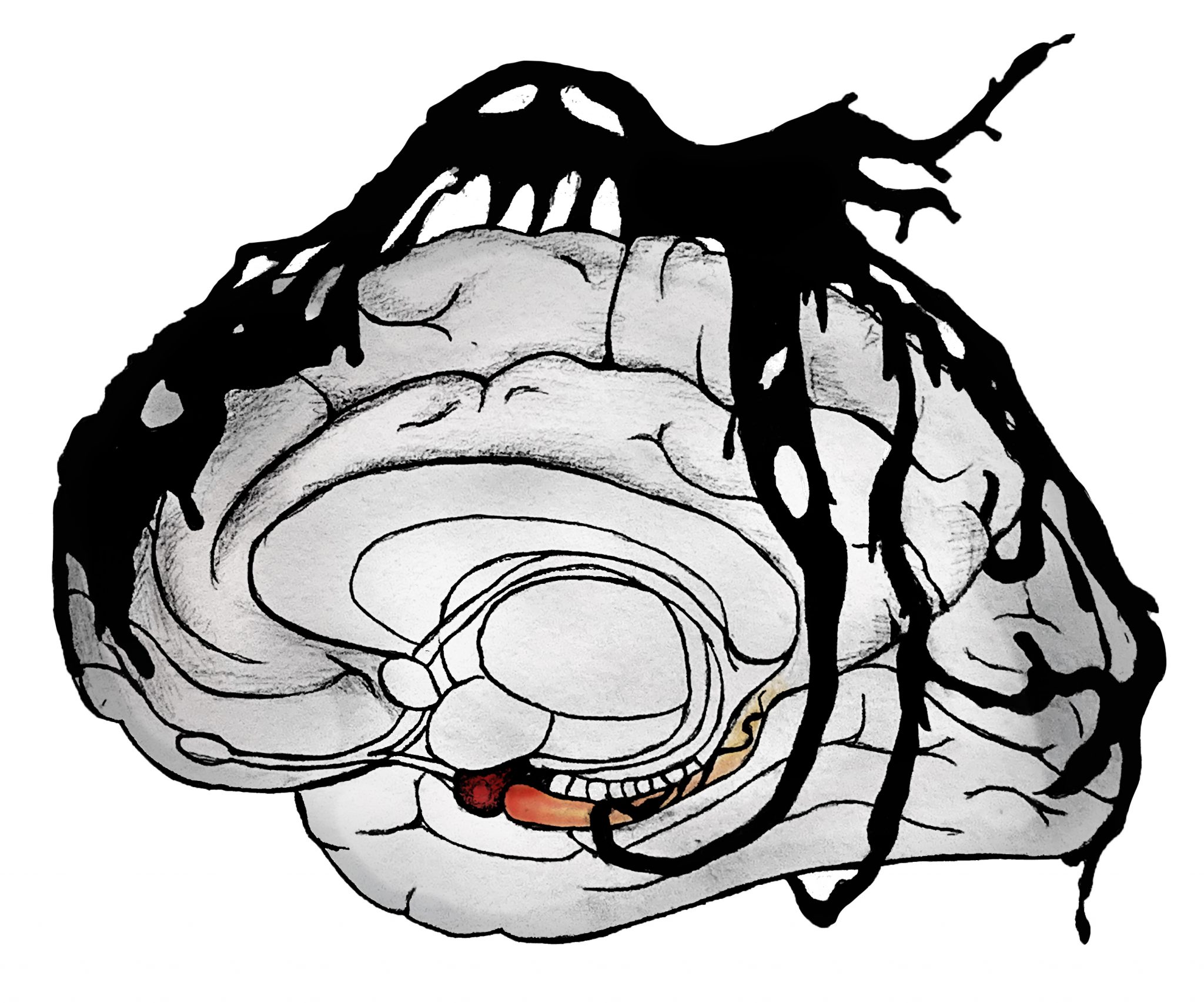

Considering these positive attributes, what impacts on the brain does meditation have that could alleviate symptoms of depression? The answer begins with a description of what we know of the mechanisms of depression. Studies have shown that depressed people display hyperactivity of the amygdala and loss of volume in the hippocampus [3, 4, 5].

The hyperactivity of the amygdala is correlated with the emotional responses of depressed patients, whose reactions to positive stimuli are negligible and reactions to negative stimuli are extreme [9]. Moreover, there is an established correlation between the atrophy of the hippocampus and increased depressive symptoms [5]. With these relationships in mind, let’s look at how meditation has been found to affect these same areas of the brain.

In recent years, studies on meditation have established links between its practice and changes in the hippocampus and amygdala, a glimmer of hope in potentially treating depression. One study published by Eileen Luders of the UCLA Department of Neurology sought to evaluate how long-term meditative practice affects the anatomy of the brain [6]. The team recruited 22 long-term active meditation practitioners and 22 controls. In order to evaluate changes in the brain’s anatomy, the researchers used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to obtain images of the participants’ brains and create models of the participants’ cerebrums, which were compared to locate any disparities in their anatomy [6]. When comparing the two groups, the team found that meditators and controls did not differ in total brain or gray matter volume. However, the meditators had larger volumes of gray matter in the hippocampus, a region responsible for functions such as emotional regulation and memory consolidation, in comparison to the controls [6]. The implications of these results are significant: they point to the possibility of using meditation to combat the atrophy of the hippocampus that is characteristic of depression.

Another study that looked into meditation’s effect on neuroanatomy was carried out by Britta Holzel of the Bender Institute of Neuroimaging [7]. Holzel’s team sought to explore how the amygdala’s gray matter density changed following an eight-week training program in mindfulness meditation called the mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) program. Twenty-seven participants were recruited to the study, all of whom underwent the full eight-week MBSR program. These participants then had multiple MRI scans taken in the week prior and in the two weeks after the intervention that were later compared to assess for differences in the density of the amygdala’s gray matter after the MBSR intervention. In their analyses of the MRI data, the team found that the gray matter density of the amygdala had decreased with meditation, an observation that coincided with participants’ self-reported decreases in stress levels [7].

Holzel and her team further researched the changes in the brain that could be facilitated by meditative practices in the years following the above study [8]. In a 2011 study, Holzel aimed to find objective measurements of changes in the brain’s anatomy that could underlie the benefits associated with meditation. Sixteen individuals were recruited to undergo the MBSR program, while another 19 were recruited to be controls. The 16 that participated in the program also had their brain scanned using MRI two weeks prior to and two weeks after the intervention. The MBSR group exhibited an increase in hippocampal gray matter by the end of the study, in contrast to a lack of changes found in the control group [8]. Like Luders’s study at UCLA, the studies conducted by Holzel and her team also point to the potential of meditation in changing the brain in ways that could help patients with depression.

The studies above show that the practice of meditation could aid in painting a better picture of what the treatment of depression might be in coming years. However, the studies referred to should be taken with a grain of salt. There are many factors to account for when establishing causal relationships between meditation and changes in the brain’s anatomy, such as the subjectivity and various forms of meditation. There are numerous practices considered to be meditation that all vary significantly, such as Kundalini yoga and loving-kindness meditation. When further exploring meditation, it is important to keep in mind that these differences in meditative forms could produce differences in results, from physiological to psychological.

While the research has yet to overcome this limitation, it may be possible to take into account this variation by studying these many practices of meditation. Another limitation is the subjectivity of the meditative experience, as it is impossible to look at the world through the eyes of someone else. This undeniable fact must be kept in mind as scientists in the field delve further into the relationship between meditation and depression.

The data recorded by Holzel and Luders in their respective studies show that there is a correlation between the practice of meditation and changes in the brain, specifically an enlargement of the hippocampal gray matter and a reduction in the size of the amygdala. These studies provide a hint that, due to the changes in the brain induced by meditation, sustained meditative practice could possibly counter the physiological symptoms of the depressed brain, specifically the atrophy of the hippocampal region and the hyperactivity of the amygdala. Meditation may not only alter the structure of the brain itself, but also its function and offer a way to aid depressed persons in search of treatment options. It is important to note that 10-30% of the world’s depressed population does not respond to the typical trial of antidepressants; this statistic shows the need to look into other viable treatments of depression, such as meditation [10]. Issues such as treatment-resistant depression currently cast a shadow over the field of psychiatry and neuroscience, a shadow that research regarding meditation and depression could shine a light on in coming years.

References

- Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (2015). Meditation—It’s Not What You Think. Mindfulness,6 (2), 393-395. doi:10.1007/s12671-015-0393-8

- Drevets, W., Videen, T., Price, J., Preskorn, S., Carmichael, S., & Raichle, M. (1992). A functional anatomical study of unipolar depression. The Journal of Neuroscience,12 (9), 3628-3641. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.12-09-03628.1992

- Sheline, Y. I. (2000). 3D MRI studies of neuroanatomic changes in unipolar major depression: The role of stress and medical comorbidity. Biological Psychiatry,48 (8), 791-800. doi:10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00994-x

- Campbell, S., & MacQueen, G. (2004). The role of the hippocampus in the pathophysiology of major depression. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience, 29 (6), 417-426.

- Luders, E., Toga, A. W., Lepore, N., & Gaser, C. (2009). The underlying anatomical correlates of long-term meditation: Larger hippocampal and frontal volumes of gray matter. NeuroImage,45 (3), 672-678. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.12.061

- Hölzel, B. K., Carmody, J., Evans, K. C., Hoge, E. A., Dusek, J. A., Morgan, L., . . . Lazar, S. W. (2009). Stress reduction correlates with structural changes in the amygdala. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience,5 (1), 11-17. doi:10.1093/scan/nsp034

- Hölzel, B. K., Carmody, J., Vangel, M., Congleton, C., Yerramsetti, S. M., Gard, T., & Lazar, S. W. (2011). Mindfulness practice leads to increases in regional brain gray matter density. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging,191 (1), 36-43. doi:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.08.006

- Murray, E. A., Wise, S. P., & Drevets, W. C. (2011). Localization of Dysfunction in Major Depressive Disorder: Prefrontal Cortex and Amygdala. Biological Psychiatry,69 (12). doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.041

- (2018, March 22). Retrieved from http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression