Hold out your hand, make a fist, and squeeze as hard as you can. If you squeeze long enough, you’ll experience some pain. This is a pain that individuals suffering from a disease known as dystonia frequently endure, most commonly in the jaw, face, vocal chords, hands, neck, and/or limbs. However, for patients with dystonia, this pain cannot be relieved by simply relaxing their muscles. For them, involuntary muscle contractions are a constant reality. It is easy to imagine the dysfunction and debilitation this disease brings about, from having trouble swallowing to difficulty walking to struggling to keep your eyes open. With no proven cure, extensive research is still ongoing on how current treatments may be improved to lessen the impact of dystonia on the daily lives of afflicted individuals.

Introduction: An Overview of Dystonia

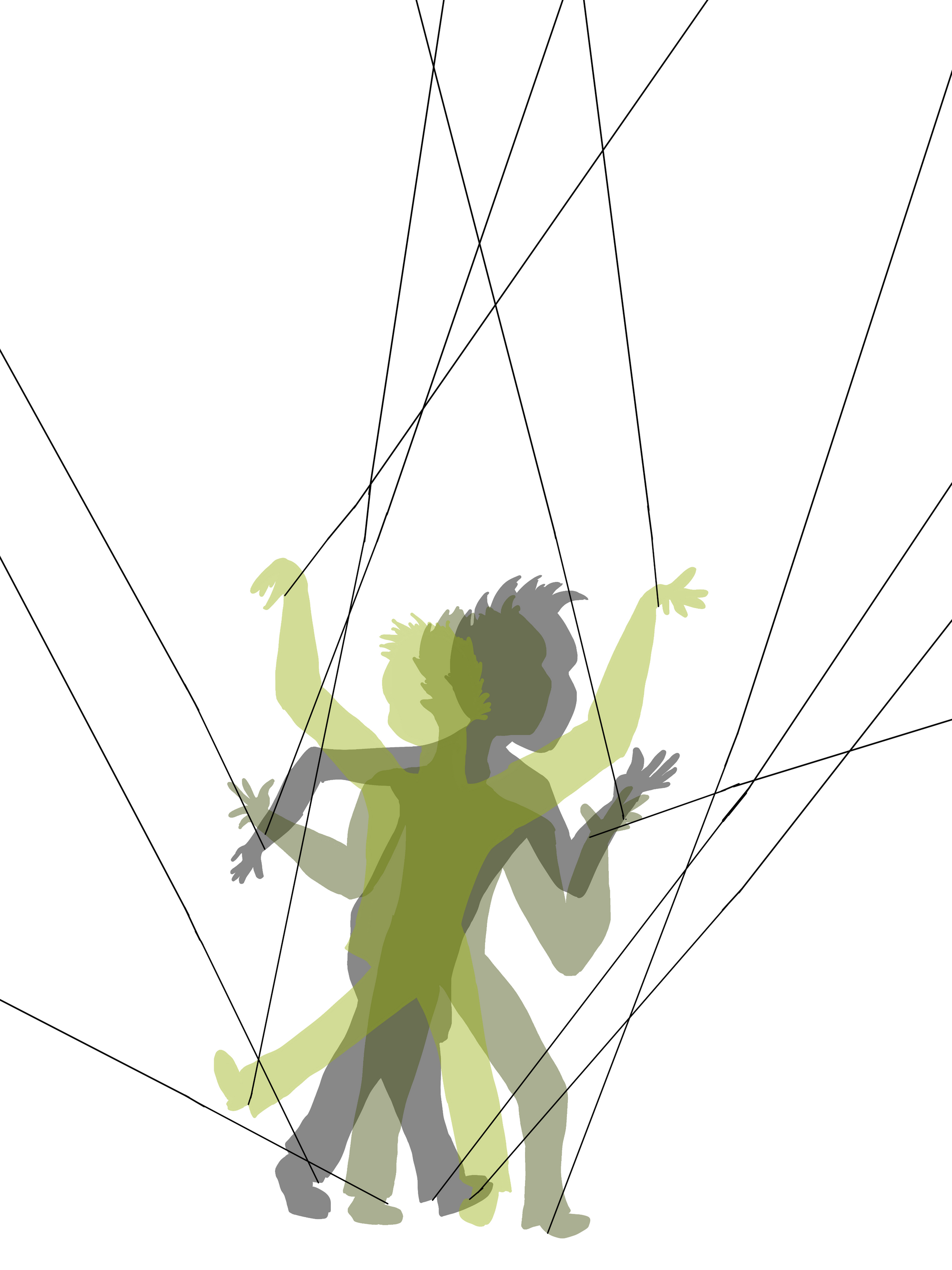

Dystonia is a neurological movement disorder characterized by involuntary muscle contractions at various locations of the body. Classifications of dystonia depend upon a variety of factors, including the age at which onset occurs, the affected body parts, and suspected causes. Symptoms may be focused in one area, or they may spread throughout the body. Some of the most common types of dystonia include cervical dystonia, blepharospasm (eyelid twitching), and focal hand dystonia (writer’s cramp). Focal dystonia affects a specific area of the body, whereas generalized dystonia involves symptoms occurring in various locations. Though researchers have yet to determine the exact pathophysiology of the disease, recent studies show that some types may involve hyperexcitability in certain parts of the brain, including the basal ganglia and the cerebellum, areas that are partly responsible for movement-related functions [1, 2]. However, there are still so many unknowns about specific dystonias that treatments typically focus solely on targeting symptoms and must be tailored to the individual’s specific type of dystonia. Along with oral medications, the most common treatments involve botulinum toxin injections and deep brain stimulation. Though both prove effective in relieving dystonic symptoms and help patients lead more functional lives, the invasive nature of injections and deep brain stimulation procedures add another layer of discomfort and difficulty that leave many dissatisfied with these treatment plans.

Botulinum Toxin

The most common nonsurgical treatment of dystonia involves botulinum toxin (Botox) injections [3]. The toxin decreases involuntary muscle contractions by inhibiting secretion of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter involved in muscle movement. Though Botox is a notably virulent neurotoxin, small, purified doses are quite effective in treating dystonia. This type of treatment involves administering injections of botulinum toxin to a targeted point of the body, typically given 12 weeks apart. Though Botox is effective at relaxing muscles, treatment success often depends upon correct placement of the injection, which is why Botox is most effective for patients with focal dystonias where the muscle contractions are concentrated in one area of the body rather than for patients with generalized dystonia where symptoms are spread across multiple areas of the body. Moreover, the need for patients to continually return to their providers for new injections impacts their quality of life. A survey of the satisfaction of cervical dystonia patients with Botox treatment found that while most patients were satisfied with the treatment, their satisfaction declined the further away they were from the previous injection, likely due to the waning effects of Botox over time [4]. Similar results were discovered in patients with cervical dystonia and blepharospasms [5]. While Botox might be initially effective at minimizing symptoms and relieving the effects of dystonia, many patients remain dissatisfied with the treatment given its gradually decreasing benefits.

Deep Brain Stimulation

For patients experiencing prolonged or severe symptoms of dystonia for which oral medications or botulinum toxin treatments are not effective, deep brain stimulation (DBS) is another, more drastic treatment option. DBS typically involves implanting one or two electrodes into the brain, which are connected by wire to a pulse generator placed under the skin near the collarbone. Similar to a pacemaker, this pulse generator emits electrical signals to targeted brain regions that control motor movements, such as the basal ganglia. There are practical limitations to this technology, however: the device requires ongoing maintenance as stimulation settings often need frequent adjustments to find the most effective setting for an individual patient, and the battery must be recharged about every four years. Research has shown that DBS is most effective for younger patients whose only neurological disorder is dystonia as well as patients with cervical dystonia or dystonia that resulted from long-term use of certain psychiatric medications [6].

Though multiple studies support the long-term effectiveness of DBS and highlight the lack of any serious side effects, there are a number of risks to the treatment that increase with age. The main concern with the implantation process of DBS is potential brain hemorrhaging. Another common concern with surgical procedures is infection but, according to the Dystonia Medical Research Foundation, this only occurs in about five percent of patients [6]. Lastly, another study found some possible long-term side effects that can arise after successful implantation of the DBS device [7]. Two dystonia patients that underwent DBS had acquired a stutter, and others had developed symptoms that aligned with Parkinson’s disease, effects which have unclear origins. The study also suggested that potential mood disorders of patients be thoroughly examined as they found multiple instances of postoperative suicide in their literature review, however this was only an observation as this was not the central question of their study [7]. Other researchers have also cited the importance of assessing the mental state of dystonia patients due to the high rates of comorbidity involving dystonia and psychiatric illnesses, including mood and anxiety disorders [8]. Despite the scarcity of research into whether DBS has a significant effect on the development of mental illness, or whether affected patients already possessed a mental disorder prior to surgical treatment, effects of treatment on patients’ mental states clearly affects their quality of life. Though DBS is effective in many cases, it also presents challenges, being not only surgically invasive during implantation but also demanding of continued maintenance, not to mention the risk of long-term physical and psychological side effects.

The invasive and risky nature of both botulinum toxin injections and deep brain stimulation contribute to the overall difficulty in treating dystonia. However, recent research studies show promising potential in the use of noninvasive alternatives such as transcranial magnetic stimulation therapy in treating patients with dystonia.

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Therapy

Although this type of treatment is typically used for psychiatric disorders like depression, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) therapy holds promising potential as a treatment for dystonia. This noninvasive therapy involves stimulating certain parts of the brain through electrical currents delivered by an electromagnetic coil that is placed on the scalp. The effects of these currents depend on the pulse rate at which they are delivered. High frequency rTMS typically excites neuronal activity in the brain, whereas low frequency rTMS tends to inhibit it [2]. There has been extensive research that has established rTMS as an effective treatment for several neurological disorders. Studies on patients with depression have found that the nerve stimulation that rTMS induces results in a significant reduction in depression symptoms compared to a placebo treatment [9, 10]. Scientists have also demonstrated that both high and low frequency rTMS produce changes in excitability of the brain, reducing motor dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease patients [11].

Due to the improvements in motor function that rTMS seems to produce, researchers are looking towards rTMS as a potentially viable non-invasive treatment for varying types of dystonia. Ideally, therapy involving low frequency rTMS would reduce some of the hyperexcitability in the brain thought to be responsible for movement dysfunction seen in dystonia and, consequently, lessen symptoms.

Several studies have investigated the effect of low frequency rTMS on the handwriting of patients with focal hand dystonia. One study found that the rTMS treatment significantly reduced tracking error and pen pressure in dystonic patients, suggesting that rTMS could be an effective therapeutic approach to focal hand dystonia and potentially other focal dystonias [12]. Another study focused on the effect of rTMS on patients with non-focal dystonia who were experiencing painful spasms. The study found that rTMS therapy reduced the pain intensity of these spasms at the end of the treatment session. However, this lessening of symptoms was temporary, and the researchers note that prolonged stimulation possible by surgical implantations such as deep brain stimulation would provide a longer lasting improvement of symptoms [13]. Some researchers have noted the potential of noninvasive brain stimulation to be used in conjunction with botulinum toxin treatments, though they emphasize that more clinical research must be conducted to test this possible treatment avenue [14].

Conclusion

Continued study into the potential of noninvasive treatments for dystonia patients offers an incredible alternative to risky, uncomfortable, and invasive treatments like Botox injections and DBS. Future research must focus on assessing and improving the effectiveness of noninvasive treatments like rTMS in both adults and children. While patients with dystonia await further research into improved treatments for the physical aspects of dystonia, many have also found more psychologically-centered therapies, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, biofeedback, and meditation, to be effective in handling some of the pain and stress from dystonia. These supplemental options help tailor treatments of dystonia to the individual. This is imperative due to the wide variety of types of dystonia as a treatment plan that works for one patient may not work for another. Treatments specific to the individual must factor in their physical and mental state before, after, and during treatment. Not only do physical symptoms affect patients’ daily lives, but the heavy emotional toll of living with a chronic neurological disease carries weight as well. Thus, finding an effective treatment that minimizes any additional difficulty that the patient must endure is imperative. A treatment approach like rTMS potentially fulfills this need for a less invasive yet effective treatment while also serving as a greater candidate for generalized treatment of dystonia, paving the way for better treatments and better quality lives.

References

[1] Vladimir K. Neychev, Xueliang Fan, V. I. Mitev, Ellen J. Hess, H. A. Jinnah, The basal ganglia and cerebellum interact in the expression of dystonic movement, Brain, Volume 131, Issue 9, September 2008, Pages 2499–2509, https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awn168

[2] Tyvaert, L., Houdayer, E., Devanne, H., Monaca, C., Cassim, F., & Derambure, P. (2006). The effect of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on dystonia: a clinical and pathophysiological approach. Neurophysiologie Clinique/Clinical Neurophysiology, 36(3), 135-143.

[3] Dystonias Fact Sheet. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/patient-caregiver-education/fact-sheets/dystonias-fact-sheet

[4] Sethi, K. D., Rodriguez, R., & Olayinka, B. (2012). Satisfaction with botulinum toxin treatment: a cross-sectional survey of patients with cervical dystonia. Journal of medical economics, 15(3), 419-423.

[5] Leplow, Bernd, Eggebrecht, Anna, & Pohl, Johannes. (2017). Treatment satisfaction with botulinum toxin: A comparison between blepharospasm and cervical dystonia. Patient Preference and Adherence, 11, 1555-1563.

[6] Deep Brain Stimulation. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://dystonia-foundation.org/living-dystonia/treatment/deep-brain-stimulation/

[7] Vidailhet, M., Jutras, M., Grabli, D., & Roze, E. (2013). Deep brain stimulation for dystonia. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 84(9), 1029-10242.

[8] Meoni, S., Zurowski, M., Lozano, A. M., Hodaie, M., Poon, Y. Y., Fallis, M., ... & Moro, E. (2015). Long-term neuropsychiatric outcomes after pallidal stimulation in primary and secondary dystonia. Neurology, 85(5), 433-440.

[9] George, M. S., Nahas, Z., Molloy, M., Speer, A. M., Oliver, N. C., Li, X. B., ... & Ballenger, J. C. (2000). A controlled trial of daily left prefrontal cortex TMS for treating depression. Biological psychiatry, 48(10), 962-970.

[10] Carpenter, L. L., Janicak, P. G., Aaronson, S. T., Boyadjis, T., Brock, D. G., Cook, I. A., ... & Demitrack, M. A. (2012). Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) for major depression: a multisite, naturalistic, observational study of acute treatment outcomes in clinical practice. Depression and anxiety, 29(7), 587-596.

[11] Lefaucheur, J. P. (2006). Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS): insights into the treatment of Parkinson’s disease by cortical stimulation. Neurophysiologie Clinique/Clinical Neurophysiology, 36(3), 125-133.

[12] Murase, N., Rothwell, J. C., Kaji, R., Urushihara, R., Nakamura, K., Murayama, N., ... & Shibasaki, H. (2005). Subthreshold low-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation over the premotor cortex modulates writer's cramp. Brain, 128(1), 104-115.

[13] Lefaucheur, J. P., Fenelon, G., Menard-Lefaucheur, I., Wendling, S., & Nguyen, J. P. (2004). Low-frequency repetitive TMS of premotor cortex can reduce painful axial spasms in generalized secondary dystonia: a pilot study of three patients. Neurophysiologie Clinique/Clinical Neurophysiology, 34(3-4), 141-145.

[14] Erro, R., Tinazzi, M., Morgante, F., & Bhatia, K. (2017). Non‐invasive brain stimulation for dystonia: Therapeutic implications. European Journal of Neurology, 24(10), 1228-E64.