Millions of people worldwide rely on antidepressants to manage their mental health, but as the use of these medications continues to rise, so do questions about their efficacy, safety, and ethical implications. From concerns about overprescriptions to the role of pharmaceutical companies in promoting these drugs, the ethics of antidepressants are complex and multifaceted. Moreover, the effectiveness of antidepressants varies greatly among individuals, with some patients reporting significant improvement while others experience little to no benefit [1]. This variability has led some critics to question the underlying chemical theories of depression and the oversimplification of mental health treatment as a matter of correcting neurotransmitter imbalances [2]. Such oversimplifications may have resulted from ambitious efforts to develop and market antidepressants to a broader patient population [3]. To understand why the market for antidepressants has progressed to this point in the modern healthcare system, we first need to take a brief walk through the history of depression and the development of its available treatment options.

Do I Have Depression?

Our modern understanding of depression is categorized into several depressive disorders, with the majority of depression diagnoses being major depressive disorder (MDD). MDD was coined by clinicians in the 1970s, and became part of the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in the 1980s [4]. Other forms of depression and depressive disorders were added to the DSM as it was revised over the next few decades including dysthymia and substance-induced depressive disorder.

According to the current edition of the DSM, a common feature of these disorders is a despondent, empty, or irritable mood, along with changes to the nervous system that affect the person’s lifestyle [5]. Using the DSM as a diagnostic manual, one may think that a simple visit to the doctor’s office can answer the question, “Do I have depression?” Unfortunately, there are no quantitative lab tests or screenings that will give a concrete yes or no answer since depression is such a complex disorder. Instead, psychiatrists use the DSM with a combination of other benchmarks and tests as a guide through the diagnostic process.

The standard self-report questionnaire used by most health professionals is the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), which consists of 21 multiple choice questions to assess the severity of depression in individuals [6]. Each question rates a specific symptom of depression on a scale of 0 to 3, where higher scores indicate a more severe depression. Because the BDI is considered a reliable and valid measure of MDD as defined in the DSM, it is widely used in both research and clinical settings as a guide to further evaluate for possible cases of depression [6]. After an initial assessment, a detailed psychiatric interview, and a review of medical history, a doctor may use several other lab tests and other physical screenings to rule out factors that share these common symptoms, such as substance abuse, medication interactions and side effects, personal lifestyles, and other underlying health conditions.

Once other possible conditions are eliminated and the patient is diagnosed with depression, the doctor considers different treatment plans based on the severity and type of depression. Many regularly updated clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for depression treatments are available to doctors, such as those from the American Psychological Association (APA), the American College of Physicians (ACP), and the U.K. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) [7]. Each set of CPGs focuses on various aspects of the treatment process, and although most agree on basic principles, there are some notable differences. For instance, NICE guidelines are mostly based on addressing interventions and care settings for the patient, while ACP guidelines primarily recommend and compare effectiveness of drug therapies [7]. The APA therapeutic plan for mild depression varies per individual, but usually begins with a prescription for an antidepressant or basic behavioral therapies. If a patient is diagnosed with moderate or severe depression, then an immediate treatment plan involving medications and lifestyle changes is discussed and arranged for the patient [8].

Serotonin and the Monoamine Hypothesis

Most guidelines recommend that clinicians offer patients a choice between psychotherapies and pharmacotherapies [8]. The standard first-line psychotherapy for moderate to severe depression follows the cognitive behavioral therapy model. This model can be split into a cognitive component that challenges negative thoughts, and a behavioral component such as exposure therapy [9]. Multiple studies support the implementation of psychotherapies in treatments for patients with depression. However, the reported efficacies of commonly recommended therapies vary, suggesting that personalized psychotherapeutic therapies may be beneficial for patients based on patient preference and accessibility [1].

Unlike psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy focuses on medication-based treatments. Scientists have been researching and developing pharmacotherapies and hypotheses of chemical imbalances for depression for over 70 years. Most of the drugs currently on the market for major depression follow the monoamine hypothesis of depression, which was first proposed in the 1950s. This hypothesis states that the deficiency of monoamines, such as serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine, in the central nervous system (CNS) is the underlying basis of depression [10]. A class of drugs called monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) were developed soon after the proposal of this theory. MAOIs work by inhibiting the activity of monoamine oxidase, which breaks down monoamines [11]. By blocking this breakdown, MAOIs increase the levels of these neurotransmitters in the CNS, enhancing their ability to regulate mood and leading to an improvement in symptoms of depression. Unfortunately, treatment with MAOIs comes with minor dietary restrictions and the risk of significant adverse side effects, leading to a decrease in MAOI prescriptions in the decades following their introduction [11].

Because of the complications that come with this class of drugs, second-generation antidepressants were synthesized and added to the market in the 1970s. These newer drug classes include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs) and work by selectively blocking the respective neurotransmitter receptors instead of targeting the monoamine oxidase enzyme [12]. Thus, the second-generation antidepressants also lead to an increase in monoamines in the CNS without sharing many side effects with MAOIs because of their different mechanisms of action [12]. However, this certainly does not mean second-generation antidepressants are free of harmful side effects.

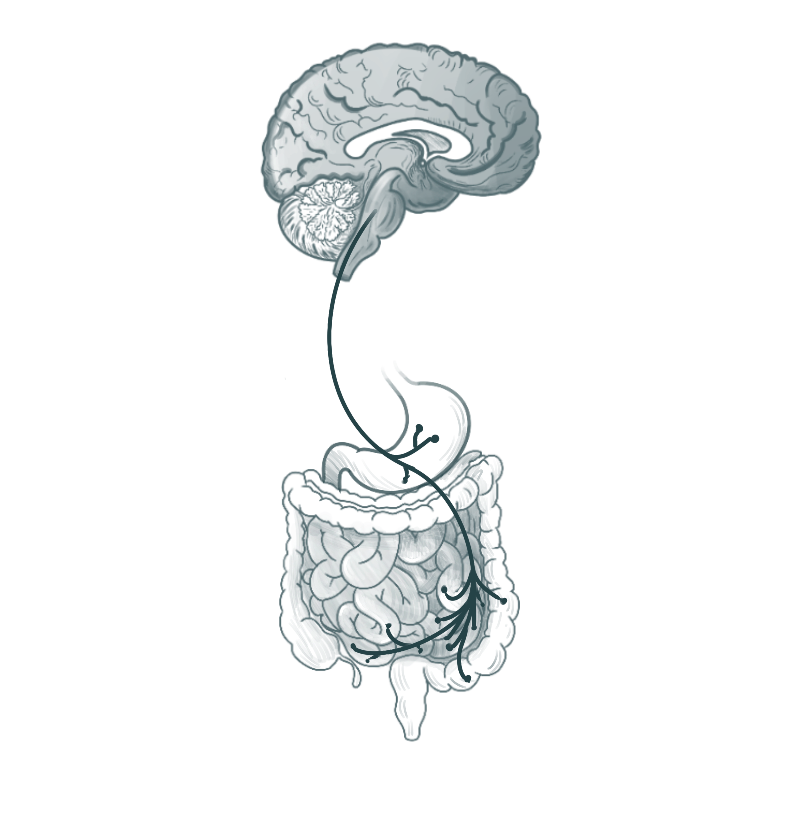

Recent research has revealed important physiological pathways that monoamine reuptake inhibitors could be involved in. For example, a study on rats shows that fluoxetine, an SSRI, can alter the balance of certain bacteria in the human microbiome known as lactobacilli, which play a role in regulating body weight [13]. The human microbiome is the collection of microorganisms mostly located in the gut. These microorganisms, such as the lactobacilli, play a crucial role in helping to regulate the immune system, digest food, and much more. The majority of serotonin in the human body is also sourced from the gut, and lactobacilli are partly responsible for synthesizing this serotonin [14]. Because of the nature of the SSRI mechanism, SSRIs can effectively inhibit the synthesis pathway of serotonin in lactobacilli and subsequently exhibit antibiotic properties. This may be helpful in niche clinical instances, but SSRIs are primarily prescribed to treat depression and not to act as an antibiotic. If this was not the intended effect, the drug could then disrupt the human microbiome and the immune system, leading to adverse effects including nausea, vomiting, and weight gain [14].

In some cases, patients who are on any class of antidepressants that successfully decrease their symptoms may also experience a rapid decrease in response to the medication after some time. This phenomenon, known as tachyphylaxis, can occur spontaneously and usually leads to treatment-resistant depression (TRD) [15]. Patients with TRD still have several therapies to choose from after exhausting the traditional first-line antidepressants. Although official CPGs are not as commonly implemented in practice compared to those for MDD, common first steps to treat TRD include the augmentation of antidepressants with other hormonal or antipsychotic drugs [15][16]. For example, in its naturally occurring salt form, lithium is usually prescribed along with other antidepressants for TRD [16]. Thyroid hormones are also sometimes prescribed since they are important mood regulators, but they are also responsible for other major metabolic pathways in the body such as bone growth and sexual maturation [17]. Finally, second-generation antipsychotics, not to be confused with second-generation antidepressants, are also augmented with antidepressants in an effort to treat TRD [18]. While it is estimated that almost a third of patients with depression eventually experience tachyphylaxis and TRD, there is no consensus on what causes these conditions, and further research is needed to develop more effective treatments [15].

Research and Development: Behind the Scenes

Despite all the associated risks, second-generation antidepressants are now one of the top prescribed drugs. In fact, one in eight patients aged 18 and older in the United States are on these medications [19]. At the same time, data shows that only half of people suffering from depression are properly diagnosed, and only half of those receive adequate treatment [12]. Thus, two issues emerge: the overprescribing and underprescribing of antidepressants. This can be largely associated with the variety of appropriate diagnoses, guidelines, and treatments for depression, which could be attributed to depression being a complex spectrum rather than a single mood disorder. For example, symptoms of melancholic depression, a subform of MDD, could appear differently compared to symptoms of atypical or seasonal depression.

To understand why some patients are not getting the treatments they need, we need to review the research methods used in clinical trials before these drugs are released into the market. The gold-standard for clinical research on antidepressants are randomized controlled trials (RCTs), which allow researchers to assess the overall quality of these drugs with minimized bias [20]. In an RCT, participants are randomly assigned to either a treatment group or a control group. The treatment group receives the intervention being tested, while the control group receives either a placebo or no treatment. The results of the trial are then compared between the two groups to determine the effectiveness of the intervention. This randomization helps reduce the risk of bias in the results and increases the validity of the findings by isolating the tested variable in question [20]. Interpreting and quantifying the results of RCTs is much more difficult due to the variability in how MDD presents itself in individuals, which also makes it challenging to research and treat using conventional methods.

The main concern with RCTs and relative pharmacotherapeutic treatments for depression is their single-disease paradigm approach [21]. The model leads to standard CPGs that treat disorders like depression as a standalone disorder rather than aiming to treat other possible underlying disorders. Providing care for one disease at a time can be ineffective and inconvenient for both the patient and provider, but this approach is still more common than one might think. A study from 2012 found that at least one-third of people diagnosed with MDD also experienced one other health condition, such as anxiety or diabetes [22]. Known as a comorbidity, this health status has shown a higher risk of developing more severe associated symptoms such as suicidal thoughts [23]. Another recent study conducted in Scotland revealed that, out of 1.8 million patients, a quarter of them experienced multimorbidity [24]. Multimorbidities describe a patient’s health when more than two health issues coexist, compared to comorbidities, which describe the relationship between only two health issues. Although instances of comorbidities were clinically recognized in the 1970s and the term multimorbidity was acknowledged in the past couple decades, the healthcare system still largely operates on a single-morbidity model. Patients with multimorbidities are often required to see multiple specialists, which can lead to miscommunication between physicians, unnecessary treatments, or other complications in patient care [24]. Until more effective and holistic treatment models are implemented into clinical research methods and treatment plans, we will not be able to efficiently manage depression and related disorders.

As we struggle to overcome the single-disease model of healthcare, we also need to acknowledge the influence of marketing on the public’s perception of depression and its available treatments. RCTs play a major role in many antidepressant advertisements and are one of the reasons why the difference in placebo effect is cited so commonly in many antidepressant advertisements. However, more studies over time have shown that the efficacy of antidepressants to placebos are not as prominent as advocated. An analysis of over 200 studies revealed there were no differences in efficacy when comparing patients with similar symptoms or in subgroups based on demographics and comorbid conditions [25]. Despite these findings, RCTs and the placebo effect remain a large part of antidepressant research and development.

After obtaining adequate results from RCTs, manufacturers apply for an approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) where the drug is subject to review. Interestingly, the FDA mandates that only two clinical trials demonstrating a difference between a drug and a placebo are necessary for a drug to make it to the market [26]. There is no constraint on the number of trials that can be carried out, and trials indicating unfavorable outcomes are not taken into account by the FDA [26]. For example, Viibryd, a newer SSRI designed to minimize side effects of the drug class, was released to the market in 2011 after going through seven RCTs. Only two of those trials demonstrated slightly better efficacy than a placebo according to guidelines, which was enough to grant an FDA approval [27]. When marketed to physicians and patients, the two pivotal trials were cited and the other five remained unpublished [28]. After the drug was approved by the FDA and released into the market, several other post-hoc studies were eventually conducted and demonstrated Vibryd’s efficacy [29].

The Patient and the Consumer

Once the antidepressant is patented under a brand name, it is primarily marketed using direct-to-consumer (DTC) advertising. Advertising a medication directly to relevant patients raises the patients’ awareness of available treatments and potentially motivates them to request that drug therapy. Because of this method’s efficiency and success, hundreds of millions of dollars each year are spent on DTC advertising to commercialize these medications [30]. As one can imagine, this tremendous effort put forth by the industry would significantly increase the rates of antidepressant prescriptions. On the other hand, DTC advertising is not shown to improve medication adherence rates. In fact, researchers found that many patients did not experience an improvement in quality of life and ability to work since they were not prepared for the side effects associated with their antidepressants [31]. From this, one can conclude that DTC advertising may downplay the side effects by overemphasizing the benefits of the medication, which could then decrease the overall outcomes by leading to medication discontinuation and patient disappointment.

Physicians are also at a loss when promotional material could be misleading. When asked about the pharmaceutical industry’s influence, one out of every three physicians said they almost always rely on industry sales representatives when deciding whether to prescribe a new drug [32]. In another study, half of the physicians participating also reported giving in to pressure to prescribe antidepressants when asked to by their patients [33]. These findings could indicate that reinforcing proper patient-centered practice by physicians is necessary and may even call for a large-scale reform of drug advertising regulations.

In a novel 2013 study, researchers aimed to quantify the impact of the chemical imbalance theories on patient preference of treatments for depression [34]. Patients experiencing depressive symptoms were tested for their monoamine levels and were given a fake result claiming their symptoms were either caused or not caused by a chemical imbalance in the brain. The patients who were told their symptoms were caused by a chemical imbalance demonstrated a more pessimistic prognosis and were more likely to opt for drug treatments over psychotherapy [34]. As a result, medications may be inappropriately prescribed where psychotherapy could be used as a more cost-effective and less invasive treatment [35]. Now a decade since this study was published, pharmacotherapy is still the primary intervention for depression, but patients have also become more aware of the effective treatments currently available. A meta-analysis of published studies shows that three-quarters of depressed patients now prefer psychotherapy over pharmacotherapy [36].

Why does patient preference matter in treating depression? Researchers investigating patient preferences in psychological treatments found that patients who had their treatment preferences met were more likely to report more positive outcomes than those who did not have their treatment preferences met. The reported outcome rates were the same regardless of whether the preference was for a drug therapy or a behavioral therapy [37]. Moreover, psychotherapy can be a safer choice in cases of depression where it is a viable option, since it avoids the risks and adverse effects of taking antidepressants altogether [38].

While antidepressants can be effective in treating depression and other mental health conditions, the potential for unintended consequences and adverse effects cannot be ignored. Additionally, the role of pharmaceutical companies in promoting and marketing these drugs must be scrutinized to prevent potential conflicts of interest. Ethical considerations around antidepressants highlight the importance of a patient-centered approach to mental health care. Ultimately, treatments for depression must prioritize the well-being and autonomy of patients and should be grounded in unbiased scientific knowledge. By addressing these ethical considerations, we can improve the quality of care for individuals with depression and promote a more compassionate and just healthcare market.

References

- Khan, A., Faucett, J., Lichtenberg, P., Kirsch, I., & Brown, W. A. (2012). A Systematic Review of Comparative Efficacy of Treatments and Controls for Depression. In C. Holscher (Ed.), PLoS ONE, 7(7), p. e41778. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0041778

- Moncrieff, J., Cooper, R. E., Stockmann, T., Amendola, S., Hengartner, M. P., & Horowitz, M. A. (2022). The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence. In Molecular Psychiatry. Springer Science and Business Media LLC. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01661-0

- Greenslit, N. P., & Kaptchuk, T. J. (2012). Antidepressants and advertising: psychopharmaceuticals in crisis. The Yale journal of biology and medicine, 85(1), 153–158.

- American Psychiatric Association. (1980). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd ed.).

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Depressive Disorders. In Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed., text rev.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787.x04_depressive_disorders

- Wang, Y. P., & Gorenstein, C. (2013). Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory-II: a comprehensive review. Revista brasileira de psiquiatria, 35(4), 416–431. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2012-1048

- McQuaid, J. R., Buelt, A., Capaldi, V., Fuller, M., Issa, F., Lang, A. E., Hoge, C., Oslin, D. W., Sall, J., Wiechers, I. R., & Williams, S. (2022). The Management of Major Depressive Disorder: Synopsis of the 2022 U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and U.S. Department of Defense Clinical Practice Guideline. Annals of Internal Medicine (Vol. 175, Issue 10, pp. 1440–1451). American College of Physicians. https://doi.org/10.7326/m22-1603

- American Psychological Association. (2019). Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of depression across three age cohorts. https://www.apa.org/depression-guideline

- David, D., Cristea, I., & Hofmann, S. G. (2018). Why Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Is the Current Gold Standard of Psychotherapy. Frontiers in psychiatry, 9, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00004

- Delgado P. L. (2000). Depression: the case for a monoamine deficiency. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 61, 7–11.

- Fiedorowicz, J. G., & Swartz, K. L. (2004). The role of monoamine oxidase inhibitors in current psychiatric practice. Journal of psychiatric practice, 10(4), 239–248. https://doi.org/10.1097/00131746-200407000-00005

- Santarsieri, D., & Schwartz, T. L. (2015). Antidepressant efficacy and side-effect burden: a quick guide for clinicians. Drugs in context, 4, 212-290. https://doi.org/10.7573/dic.212290

- Lyte, M., Daniels, K. M., & Schmitz-Esser, S. (2019). Fluoxetine-induced alteration of murine gut microbial community structure: evidence for a microbial endocrinology-based mechanism of action responsible for fluoxetine-induced side effects. PeerJ, 7, 6199. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.6199

- Gao, K., Mu, C. L., Farzi, A., & Zhu, W. Y. (2020). Tryptophan Metabolism: A Link Between the Gut Microbiota and Brain. Advances in nutrition, 11(3), 709–723. https://doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmz127

- Katz G. (2011). Tachyphylaxis/ tolerance to antidepressive medications: a review. The Israel journal of psychiatry and related sciences, 48(2), 129–135.

- Voineskos, D., Daskalakis, Z. J., & Blumberger, D. M. (2020). Management of Treatment-Resistant Depression: Challenges and Strategies. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment, 16, 221–234. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S198774

- Brent G. A. (2012). Mechanisms of thyroid hormone action. The Journal of clinical investigation, 122(9), 3035–3043. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI60047

- El-Khalili, N., Joyce, M., Atkinson, S., Buynak, R. J., Datto, C., Lindgren, P., & Eriksson, H. (2010). Extended-release quetiapine fumarate (quetiapine XR) as adjunctive therapy in major depressive disorder (MDD) in patients with an inadequate response to ongoing antidepressant treatment: a multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. The international journal of neuropsychopharmacology, 13(7), 917–932. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1461145710000015

- Brody DJ, Gu Q. (2020). “Antidepressant use among adults: United States, 2015–2018.” National Center for Health Statistics.

- Hariton, E., & Locascio, J. J. (2018). Randomised controlled trials - the gold standard for effectiveness research. BJOG: An international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology, 125(13), 1716. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.15199

- Ecks, S. (2021). Depression, Deprivation, and Dysbiosis: Polyiatrogenesis in Multiple Chronic Illnesses. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry, 4(45), pp. 507–524. Springer Science and Business Media LLC. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-020-09699-x

- Thaipisuttikul, P., Ittasakul, P., Waleeprakhon, P., Wisajun, P., & Jullagate, S. (2014). Psychiatric comorbidities in patients with major depressive disorder. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment, 10, 2097–2103. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S72026

- Mykletun, A., Bjerkeset, O., Dewey, M., Prince, M., Overland, S., & Stewart, R. (2007). Anxiety, depression, and cause-specific mortality: the HUNT study. Psychosomatic medicine, 69(4), 323–331. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e31803cb862

- Barnett, K., Mercer, S. W., Norbury, M., Watt, G., Wyke, S., & Guthrie, B. (2012). Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet, 380(9836), 37–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2

- Gartlehner, G., Hansen, R. A., Morgan, L. C., Thaler, K., Lux, L., Van Noord, M., Mager, U., Thieda, P., Gaynes, B. N., Wilkins, T., Strobelberger, M., Lloyd, S., Reichenpfader, U., & Lohr, K. N. (2011). Comparative benefits and harms of second-generation antidepressants for treating major depressive disorder: an updated meta-analysis. Annals of internal medicine, 155(11), 772–785. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-155-11-201112060-00009

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2019). “Demonstrating Substantial Evidence of Effectiveness for Human Drug and Biological Products.” https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/demonstrating-substantial-evidence-effectiveness-human-drug-and-biological-products

- Administration. UFaD. “Vilazodone Drug Approval Package.” (2011). http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2011/022567Orig1s000TOC.cfm.

- Wang, S.-M., Han, C., Lee, S.-J., Patkar, A. A., Masand, P. S., & Pae, C.-U. (2015). Vilazodone for the Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder: Focusing on Its Clinical Studies and Mechanism of Action. Psychiatry Investigation, 2(12), p. 155. Korean Neuropsychiatric Association. https://doi.org/10.4306/pi.2015.12.2.155

- Wang, S. M., Han, C., Lee, S. J., Patkar, A. A., Masand, P. S., & Pae, C. U. (2016). Vilazodone for the Treatment of Depression: An Update. Chonnam medical journal, 52(2), 91–100. https://doi.org/10.4068/cmj.2016.52.2.91

- Kravitz, R. L., Epstein, R. M., Feldman, M. D., Franz, C. E., Azari, R., Wilkes, M. S., Hinton, L., & Franks, P. (2005). Influence of patients' requests for direct-to-consumer advertised antidepressants: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 293(16), 1995–2002. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.293.16.1995

- Tamburrino, M. B., Nagel, R. W., Chahal, M. K., & Lynch, D. J. (2009). Antidepressant medication adherence: a study of primary care patients. Journal of clinical psychiatry, 11(5), 205–211. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.08m00694

- Anderson, B. L., Silverman, G. K., Loewenstein, G. F., Zinberg, S., & Schulkin, J. (2009). Factors associated with physicians' reliance on pharmaceutical sales representatives. Academic medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 84(8), 994–1002. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ace53a

- Lewis, P. J., & Tully, M. P. (2011). The discomfort caused by patient pressure on the prescribing decisions of hospital prescribers. Research in social & administrative pharmacy, 7(1), 4–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2010.02.002

- Kemp, J. J., Lickel, J. J., & Deacon, B. J. (2014). Effects of a chemical imbalance causal explanation on individuals’ perceptions of their depressive symptoms. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 56, pp. 47–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2014.02.009

- Lazar, S. G. (2014). The Cost-Effectiveness of Psychotherapy for the Major Psychiatric Diagnoses. Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 42(3) pp. 423–457. Guilford Publications. https://doi.org/10.1521/pdps.2014.42.3.423

- McHugh, R. K., Whitton, S. W., Peckham, A. D., Welge, J. A., & Otto, M. W. (2013). Patient Preference for Psychological vs Pharmacologic Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 74(6), pp. 595–602. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.12r07757

- Gelhorn, H. L., Sexton, C. C., & Classi, P. M. (2011). Patient preferences for treatment of major depressive disorder and the impact on health outcomes: a systematic review. The primary care companion for CNS disorders, 13(5). https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.11r01161

- Kamenov, K., Twomey, C., Cabello, M., Prina, A. M., & Ayuso-Mateos, J. L. (2017). The efficacy of psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy and their combination on functioning and quality of life in depression: a meta-analysis. Psychological medicine, 47(3), 414–425. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716002774