Introduction

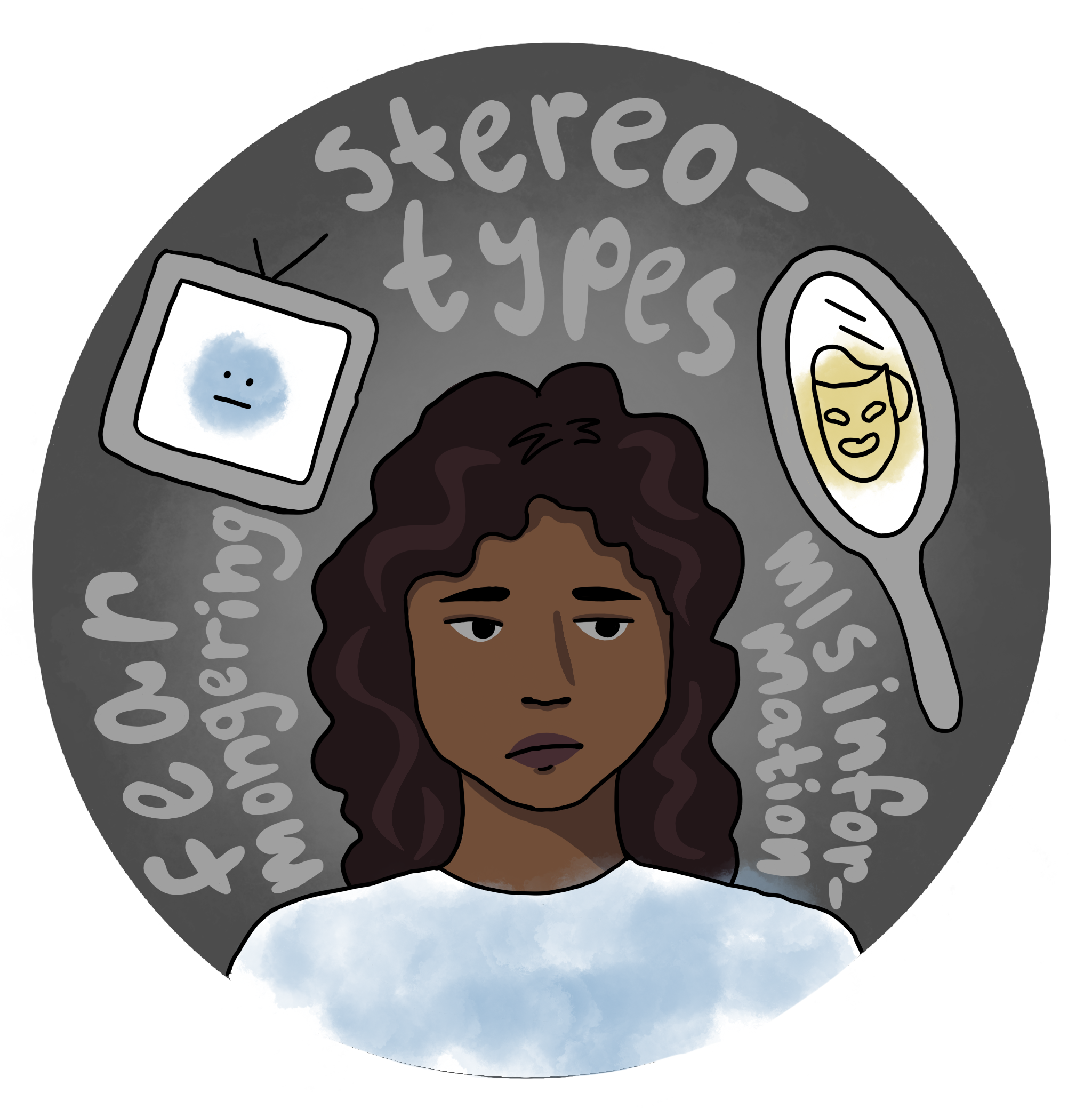

In the British Isles, centuries-old stories warn that one must keep a close watch on a newborn child, lest the fairies steal it away and replace it with one of their own: one who is near indistinguishable from the “original.” These legends go on to list the tell-tale signs of “changelings,” from suddenly failing to speak, having a perception beyond their years, being unresponsive, and avoiding eye contact. Though no longer as widely believed in, the ramifications of such stories are troubling when you consider that many of the traits described above align with symptoms of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), one of the more misrepresented mental diagnoses currently in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

From the age-old fear mongering of the changeling myth to the modern-day stereotypes of amoral savants, autistic people have been characterized as anywhere from “super-intelligent” to “completely helpless," all circling back to a desire to categorize them as abnormal. This is contrary to the fact that 2.5% of the population in the United States, or nearly 9,000,000 people, are diagnosed with ASD according to a 2014-2016 survey by the CDC [1]. Chances are, the reader of this article knows someone who is autistic or is even autistic themselves.

One idea that has become popular in recent years is that people with ASD lack empathy [2]. This has only reinforced misconceptions and does not stand up to rigorous research. A study investigating the differing views on autism between neurotypicals and people with a diagnosis found that those diagnosed with autism reported feeling “empathy overload.” Still, others stated that their experience with empathy depended on the situation and the people involved [2]. The study did not clarify how those with autism experience empathy on a neurological level. The answer to this perceived discrepancy and the key to dispersing negative stereotypes concerning autism lies in the nature of empathy itself.

Anatomy of Empathy

Empathy is typically thought in the public landscape as a one-dimensional concept, equated in many cases with ‘sympathy’ and, by extension, with compassion. Many believe that to feel empathy is to be kind or feel sad for another, and that it is essential to what makes us human. Considering this, it’s easy to think that empathy is an all-or-nothing trait: you either possess empathy, or you don’t.

This, however, is an extreme oversimplification of empathy and its functional components, which involve many different complex facets [3]. The bulk of research into the connection between empathy and ASD focuses on two main components: cognitive empathy and affective empathy. Cognitive empathy (CE) is the ability to understand what another person is feeling. Being able to look at someone and recognize that they are sad, angry, disgusted, or afraid is an example of CE [3]. CE is heavily associated with activity in the neocortex, a large section of the brain reserved for cognition and spatial reasoning [4]. Affective or emotional empathy (AE), on the other hand, is the ability to feel another’s emotions as if they were your own [3]. If you see your friend start to cry and have the sudden urge to cry as well, that’s an expression of AE. This component is associated with activity in the amygdala [5]. It is responsible for processing stimuli and activating responses concerning fear and anger, such as the “fight, flight, or freeze” response. These responses are regulated by the ventromedial prefrontal cortex at the forefront of the brain, which plays a role in decision-making [5]. AE is also associated with the anterior cingulate cortex, which processes and predicts rewards and is associated with responses to other people’s pain [6].

Both components of empathy have different origin points and different purposes in the brain. Twin studies using pairs of fraternal and identical twins have suggested that CE and AE develop separately. In investigations of identical twins’ upbringing in shared versus separate environments, AE was found to be influenced more by genetics whereas CE was influenced by the environment [7]. These two components of empathy can develop out of sync from one another, due to the multitude of biological and environmental factors that influence development. This can result in empathic disequilibrium, when someone exhibits a different level of one empathic component over the other [8]. One example is high amounts of AE and low amounts of CE, causing one to feel others’ emotions as if they were their own, while not understanding why they are feeling that way since they can’t discern the other’s emotions from their expression.

Root Causes of ASD and Masking

The harmful presumption in the public conscience that a symptom of ASD is empathy deficiency, or an inability to connect with others, has led to the negative stereotypes concerning amoral savants discussed before. As a result, many past studies have focused on finding the missing piece in an autistic brain that makes an autistic person so different from a neurotypical.

One meta-analysis of previous studies on empathy in autism suggested autistic individuals were deficient in both CE and AE, with a more significant CE difference compared to neurotypical participants. This meta-analysis also found that there was a bias towards studies involving CE, with the possibility that studies involving AE could have gone unpublished or buried as the publishers favored one theory. Without acknowledging the possibility of AE being affected, the perception of autism skewed into a deficit in CE [9]. This skew is in spite of examples where autistic people were shown to score higher in AE than neurotypical participants. As a result, empathic disequilibrium has been investigated as the common symptom in autistic cases [8].

It is also thought that many autistic traits, including those associated with attention and sensory processing, might have developed in response to overarousal. Arousal refers to any physical or mental activity and typically fluctuates throughout the day. For example, emotional stimuli and one’s reactions to them can overwhelm a person easily. Arousal levels are regulated through various systems, such as those that focus on memory and learning [10]. It is substantially more difficult to identify the symptoms of autism caused by overarousal.

Though ASD is one of the more recognizable mental diagnoses, the actual process of diagnosis is far from an exact science. As previously stated, misconceptions run abound and many people can go their whole lives without a diagnosis or speculating they might be on the spectrum. Not to mention, all these factors contributing to the presentation of an individual's ASD can in turn lead to a variety of symptoms, a common one being masking. Masking is defined as hiding one’s symptoms and is common in cases of “high-functioning” ASD, especially seen in women [11]. Masking comes about when a person believes their symptoms make them strange, undesirable, or even threatening, causing them to hide those symptoms. Examples of masking include forcing eye contact, learning to read social cues, and preventing self-stimulating behavior. Masking overall is mentally draining and, in extreme cases, can damage one’s mental health. Masking also becomes harder to recognize over time, because the longer someone masks, the harder it is to “un-mask,” causing undiagnosed individuals to slip under the radar [12]. The negative stereotypes and misconceptions of ASD don’t help matters.

Study Results and Implications

Given the complex diagnostic process, the link between ASD and empathic disequilibrium warrants further analysis. In a study investigating the link between ASD and empathic disequilibrium, participants’ autistic traits were measured against their empathy levels for both cognitive and affective components. This study found that a difference in levels of CE and AE was positively correlated with a diagnosis of autism and experiencing autistic traits, not just empathy deficiency [8]. It has also been found that higher levels of AE were correlated with increased connectivity between the amygdala and other areas heavily involved with emotions and cognition [13]. Scores of an empathy questionnaire measuring CE and “emotional reactivity,” a stand-in for AE, were compared to scores on an autism questionnaire. It was found that autistic traits were correlated with experiencing higher levels of AE compared to CE [13]. All this goes to show that autistic traits and diagnoses are correlated with experiencing empathic disequilibrium, far from a complete deficiency in empathy as was once thought.

Further Applications

It was speculated that ASD is linked to deficiencies in aforementioned arousal systems, as many ASD symptoms and behaviors have to do with increased arousal. This includes difficulty sleeping and emotional dysregulation [11]. AE and the disequilibrium involving it can be linked to this theory, as increased AE led to overarousal due to an increased ability to feel others’ emotions. This overwhelms the arousal systems, leading to difficulty regulating attention, decreased awareness, and elevated anxiety [8].

As seen with the studies looked over, empathic disequilibrium can be linked to exhibiting autistic traits in individuals both diagnosed and not, potentially offering a new method to diagnosis in a clinical setting. ASD is already heavily under-diagnosed, especially in women and adults [14]. This is suspected to be because of underlying biases concerning women and effects of masking [14].

Increased understanding of empathy and its connection to ASD can help improve diagnostic criteria, thus ensuring that the undiagnosed, whether they mask or not, can access the help they need. Spreading this knowledge could help destigmatize ASD and enable people who didn’t realize they were on the spectrum to put a name to their experiences. Finally, this can open new doors to further research into how autistic brains differ from neurotypical brains, the source behind many autistic traits, and help us work towards learning more about this diagnosis that’s so prevalent in the human population.

Conclusion

With further research and the willingness to leave behind preconceived notions of how our own minds and the minds of our neighbors work, life can become just a little more comfortable and those with autism can feel just a little more understood. Every brain is unique and every individual’s perception of reality is shaped and formed by their experience, their personality, their upbringing and indeed, their biology and neurological network. Understanding that can make a significant difference in another’s day-to-day life all the way to the clinical world, where even a little bit of awareness can improve the lives of autistic people, both those who have already been diagnosed and those who might not be aware.

References

- Salari, N., Rasoulpoor, S., Rasoulpoor, S., Shohaimi, S., Jafarpour, S., Abdoli, N., Khaledi-Paveh, B., & Mohammadi, M. (2022). The global prevalence of autism spectrum disorder: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Italian journal of pediatrics, 48(1), 112. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-022-01310-w

- Gillespie-Lynch, K., Kapp, S. K., Brooks, P. J., Pickens, J., & Schwartzman, B. (2017). Whose expertise is it? evidence for autistic adults as critical autism experts. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00438

- Riess H. (2017). The Science of Empathy. Journal of patient experience, 4(2), 74–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/2374373517699267

- Zheng, H., Huang, D., Chen, S., Wang, S., Guo, W., Luo, J., Ye, H., & Chen, Y. (2016). Modulating the activity of ventromedial prefrontal cortex by anodal tDCS enhances the trustee’s repayment through altruism. Frontiers in Psychology, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01437

- Rolls E. T. (2019). The cingulate cortex and limbic systems for emotion, action, and memory. Brain structure & function, 224(9), 3001–3018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-019-01945-2

- Lockwood, Patricia. L., Apps, M. A. J., Roiser, J. P., & Viding, E. (2015). Encoding of vicarious reward prediction in anterior cingulate cortex and relationship with trait empathy. The Journal of Neuroscience, 35(40), 13720–13727. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.1703-15.2015

- Abramson, L., Eldar, E., Markovitch, N., & Knafo‐Noam, A. (2022). The empathic personality profile: Using personality characteristics to reveal genetic, environmental, and developmental patterns of adolescents’ empathy. Journal of Personality, 91(3), 753–772. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12772

- Shalev, I., Warrier, V., Greenberg, D. M., Smith, P., Allison, C., Baron-Cohen, S., Eran, A., & Uzefovsky, F. (2022). Reexamining empathy in autism: Empathic disequilibrium as a novel predictor of autism diagnosis and autistic traits. Autism research : official journal of the International Society for Autism Research, 15(10), 1917–1928. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2794

- Fatima, M., Babu, N. Cognitive and Affective Empathy in Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Meta-analysis. Rev J Autism Dev Disord (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-023-00364-8 )

- Orekhova, E. V., & Stroganova, T. A. (2014). Arousal and attention re-orienting in autism spectrum disorders: evidence from auditory event-related potentials. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 8, 34. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00034

- Miller, D., Rees, J., & Pearson, A. (2021). "Masking Is Life": Experiences of Masking in Autistic and Nonautistic Adults. Autism in adulthood : challenges and management, 3(4), 330–338. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2020.0083

- Funawatari, R., Sumiya, M., Iwabuchi, T., & Senju, A. (2024). Double-edged effects of social strategies on the well-being of autistic people: Impact of self-perceived effort and efficacy. Brain Sciences, 14(10), 962. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14100962

- Shalev, I., & Uzefovsky, F. (2020). Empathic disequilibrium in two different measures of empathy predicts autism traits in neurotypical population. Molecular autism, 11(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-020-00362-1

- McCrossin R. (2022). Finding the True Number of Females with Autistic Spectrum Disorder by Estimating the Biases in Initial Recognition and Clinical Diagnosis. Children (Basel, Switzerland), 9(2), 272. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9020272