Introduction

Dance is communication. People often communicate their feelings through body language – feelings of elation, discomfort, misery – but if body language is a whisper, dance can sound like someone is screaming in your ear. This is all due to intentional movement. A single twitch can reveal a person’s thoughts, feelings, and stories. A powerful dance performance is enough to bring the audience to tears. But what if dance has the potential to be more than an art form?

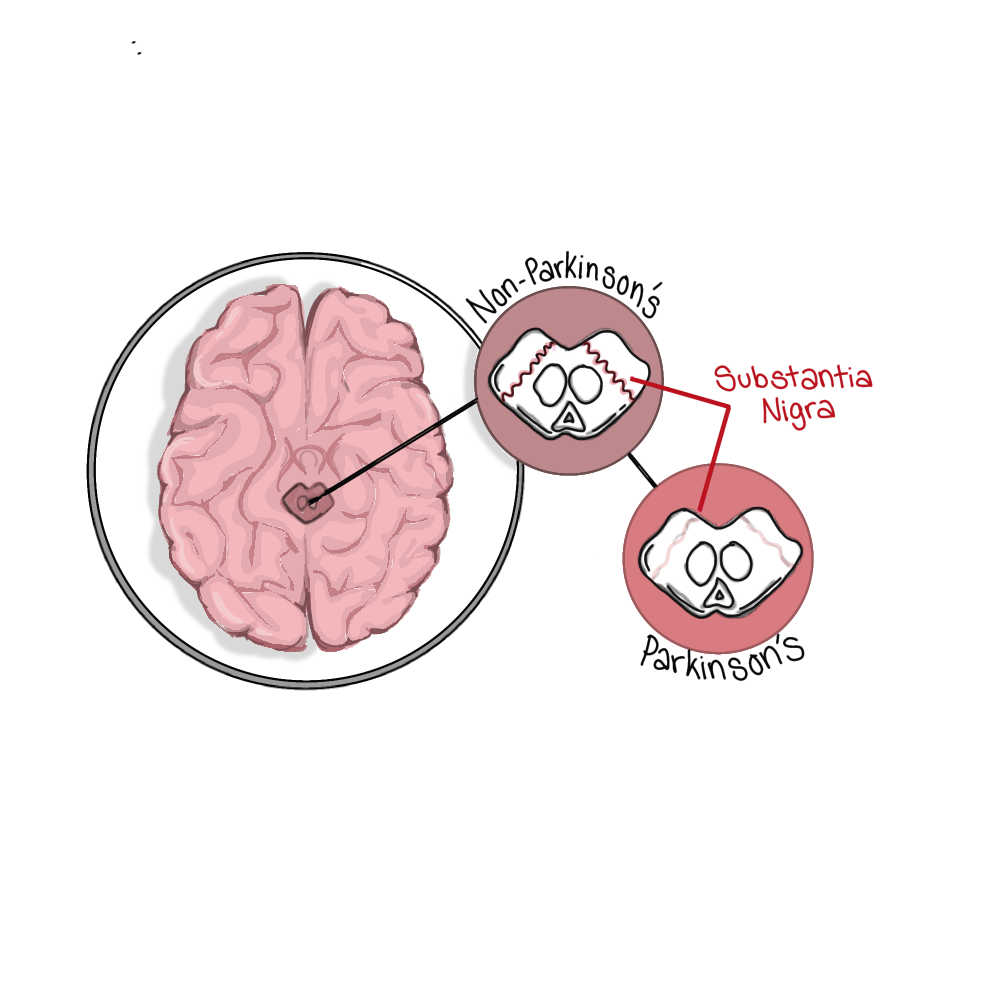

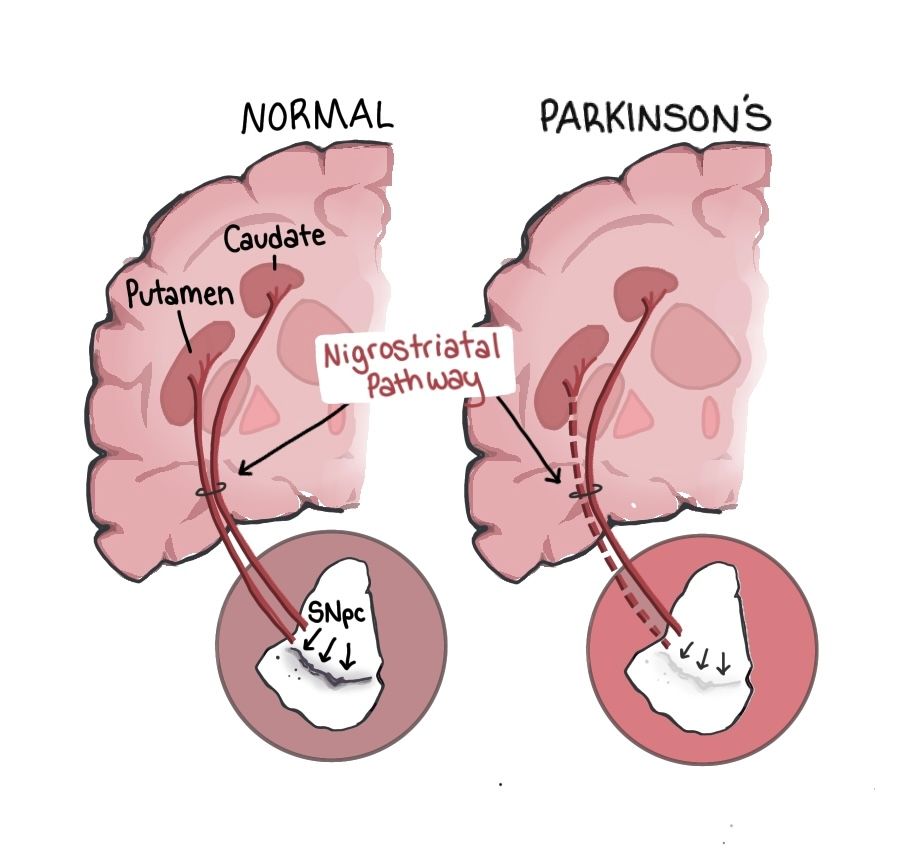

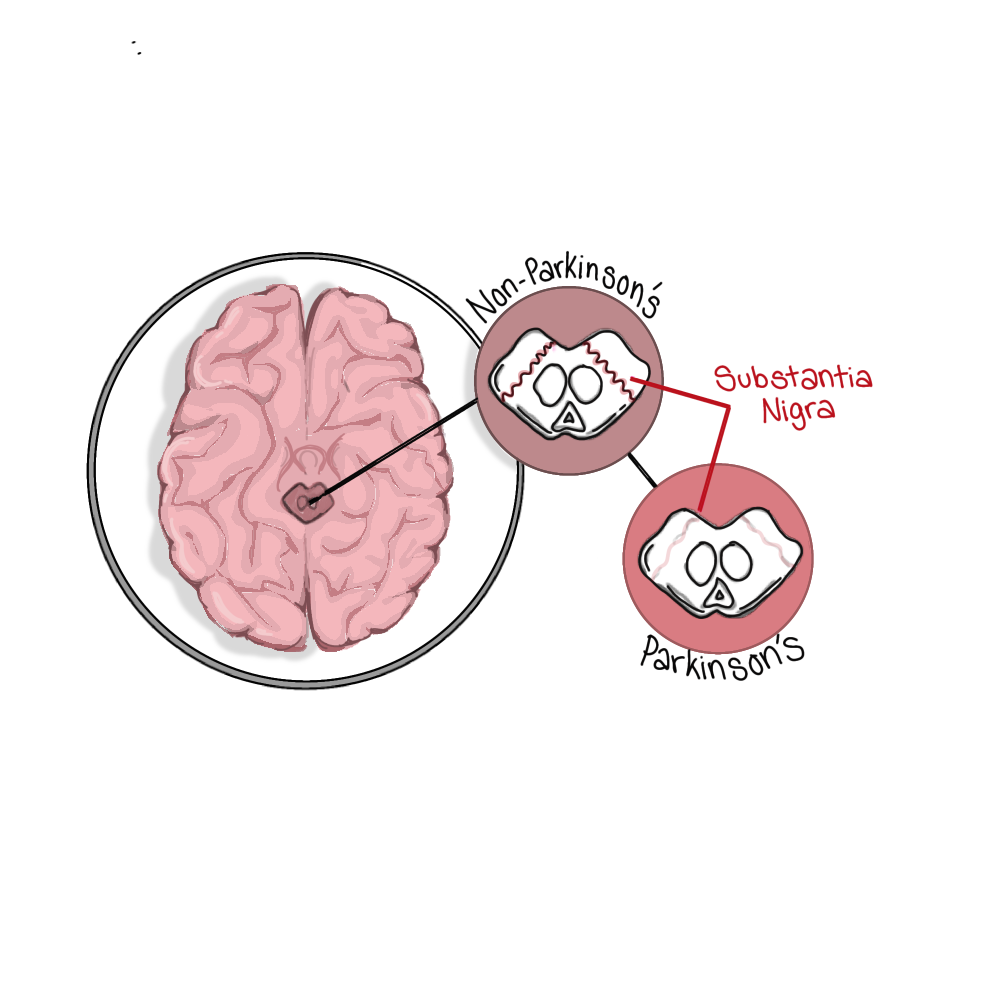

Dance is characterized by voluntary movement, but recent research has shown that it could help combat involuntary movements such as those exhibited by Parkinson’s patients. Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a movement disorder where patients often experience a myriad of involuntary motor complications that take control over their everyday lives, complications such as tremors at rest, rigidity, slowness of movement, posture instability, and freezing episodes where the patient is unable to move at all [1]. Because of these symptoms, patients’ quality of life is significantly affected – everyday activities such as dressing, eating, or even standing up straight for long periods of time are impaired. PD is caused by the death of 60%-70% of dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter known for providing movement regulation in the brain [2]. Another known contributing factor is the presence of “Lewy Bodies,” tumor-like clumps full of protein and cytoplasm. These clumps reduce the connectivity to the striatum and the basal ganglia network, which also controls voluntary movement. Parkinson’s is the most common movement disorder and the second most common age-related neurodegenerative disease after Alzheimer’s, so it should be no surprise that preventative measures and treatments have been developed [1].

Existing Treatments

While there is no cure for PD, scientists have developed many treatments to help alleviate symptoms. One of the most common treatments is levodopa, a precursor to dopamine that aims to counteract the loss of the neurotransmitter. In the early stages of PD, levodopa has proven to be quite beneficial, but, as the disease progresses, patients fluctuate between “good” anti-Parkinsonian effects and ineffective treatment. Patients may begin to experience side effects such as fluctuation in motor response, involuntary movement (dyskinesia), nocturnal confusion, vivid dreams, and hallucinations. Specifically, the resulting dyskinesia is almost ironic, as the side effects mimic the symptoms levodopa is trying to treat in the first place. As the patient continues to take levodopa, the efficacy of the drug decreases, requiring a larger dosage. This positive feedback loop continues throughout the patient’s life [3]. Another recent treatment is the use of deep-brain stimulation (DBS), which involves inserting electrodes into the brain and exciting or inhibiting neural pathways in order to subdue neural activity in the basal ganglia loop, commonly termed “jamming” the diseased network. Some theories suggest that DBS alters the release of neurotransmitters at the synapses. DBS has been shown to be effective at treating PD symptoms when pharmaceuticals do not work. However, it is a very expensive and invasive surgery, meaning that it is not accessible to the widespread public. Patients who do receive the surgery are subject to the risk of an incorrect voltage setting: too high and the patient experiences dyskinesias akin to the side effects of levodopa; too low, and the treatment is not effective at all [4]. Some scientists are now researching alternative, unconventional treatment methods. One such method is dance therapy.

Dance Therapy

Dance therapy for Parkinson’s is exactly what one might imagine: a typical dance class that aids patients in finding the motor coordination and muscle movement that have been weakened by Parkinson’s symptoms. Classes focus on rhythm, balance, control of posture, and overall controlled movement, allowing patients to combat the motor symptoms associated with Parkinson’s [5]. In addition, dance has been demonstrated to improve overall quality of life, helping patients to gain a sense of positive identity after their diagnosis [6]. A typical dance therapy session is structured with a warm-up, barre exercises, movement across the floor, and choreography at the end of class led by a professional dancer with certified Parkinson’s dance therapy training [7]. Exercises are geared towards reinstituting balance lost through symptoms. Practicing rhythm allows patients to remember the movements and create dynamics in order to avoid freezing in locked positions. All these practices lead to choreography, which further helps train coordination, memory, and spatial orientation, stitching the otherwise monotonous exercises into a beautiful piece of art [7].

Dance Therapy Studies

Non-pharmacological methods of treatment, such as dance therapy (DT), are increasing in popularity as complementary therapies. Studies have shown that PD patients who participate in dance therapy have experienced a significant decline in motor and cortical symptoms [6][9][11]. One such study examined sixteen patients with a recent history of falls divided into two treatment groups: dance therapy and traditional rehabilitation [8]. After 10 weeks, participants were tested with multiple movement tests, assessing physical factors such as balance, gait, walking, and speed, as well as cognitive factors such as attention, speed, and processing abilities. Not only did the DT participants perform better in these tests, but examination during the follow-up also showed that they retained the benefits of DT eight weeks after the study’s conclusion . In contrast, patients who participated in only traditional rehabilitation therapy experienced changes that were inconsistent and did not last very long. It is important to note that the duration of this study could have been too short to find any significant results for the traditional rehabilitation group, since the traditional rehabilitation was adapted to fit the timeline of the DT program. Nonetheless, the benefits of DT show that it has relevant impacts on both motor and non-motor functions [8].

While the previous study was based on a traditional ballet-technique dance class, other studies employ different dance styles that allow for both self-motivated movement as well as externally directed movement, like ballroom dancing. Most dance styles typically involve moving of one’s own accord–deciding when to reach an arm, moving two steps forward or two steps back, whether to leap above the clouds or melt into the floor [9]. However, this is not the case with ballroom dance, since it includes both leading and following, which is why other scientists decided to focus on the tango as a method of dance therapy [9]. Accordingly, the characteristic firm walking steps and quick stops and starts could counteract freezing episodes [10]. This study divided participants into two groups: one trained in Argentine Tango and the other engaged in traditional group-based physiotherapy [9]. Participants were assessed with multiple movement-based and cognitive tests before and after the study, and while most participants had relatively similar results, the Argentine Tango group showed a slight but statistically insignificant improvement in motor activity. The study reported a decrease in motor sign severity in Parkinson’s after the intervention in both groups with no significant difference between them, suggesting a positive effect of sustained physical activity from both dance and traditional physical therapy [9].

These particular studies were short-term; other scientists chose to investigate the progression of DT treatment over a longer period of time, which can allow them to ask questions about neuroplasticity and the brain’s ability to strengthen neural pathways over time. In a study by Bears and DeSouza, 32 patients of mild severity PD were studied over a period of 3 years [11]. Patients trained in weekly 1.25-hour dance classes, including a warm-up, barre exercises, movement across the floor, and choreography. These particular dance classes were structured with PD symptoms in mind, taking into account factors such as training intensity, speed of rhythm, balance, cognition, motor skill, physical confidence, activity duration, and movement pattern. To serve as a reference group, other patients experienced no dance therapy of any kind. The participants who danced once a week experienced a slower onset of motor-related symptoms compared to the control group. Considering the fact that the control group experienced a faster decline in symptoms in comparison to those who undertook DT, the results of this study are promising and suggest that DT may have neuroprotective effects in PD by increasing the levels of BDNF, a growth protein that repairs damaged areas and protects against further neurodegeneration [11].

Discussion

While these studies show promise, there remain substantial limitations that require discussion. For instance, all of the studies have a relatively low sample size, which makes it difficult to draw definite conclusions and lacks generalizability. All of the studies mentioned should be regarded on a case-by-case basis. All bodies are different, and when considering physical, movement-based therapies, what works for one person may not work for another. Dance therapy is also relatively new in the realm of Parkinson’s treatment. It has been difficult to recruit volunteers and even more difficult to retain them for the duration of the study. In addition, more studies on a wider scale are needed to explore the lifetime effect of dance therapy in order to draw the necessary conclusions of causality.

Conclusion

The purpose of dance therapy is not to cure Parkinson's disease, but rather to act as a complement to pharmacological treatment. The presence of intentional movement can counteract the problematic side effects that levodopa introduces for those who take it [5]. Dance engages all parts of the body, activating muscles to point your toes and other muscles to lift your chin, while stitching together individual movements. Past participants commented, “it works all parts of the body and I think that makes a lot of difference because when you’ve finished you feel as if you’ve moved every joint.” While dance allows for free-form movement, classes are also very guided. The presence of a teacher explaining the purpose of every movement helps patients genuinely enjoy the class, making it seem like more of a hobby than a mandated form of treatment. Participants explained, “they stop at each [exercise] and explain [it] and it gives you a chance to understand what the exercises are for…they don’t just do it for the sake of it, it is there for a reason” [5]. With dance comes a community built on support and a love for movement. While these evaluations are not quantitative by any means, the participants’ qualitative feedback shows that incentive to show up to class is an important factor in their treatment and growth.

The world of dance is becoming more and more inclusive every day. This accessibility is what sets dance therapy apart from many other more expensive treatments such as deep brain stimulation. Additionally, it helps combat the side effects of traditional treatments such as levodopa with its ability to stimulate the motor aspects of the brain. Organizations such as Dance for PD, NeuroTango, and Dance Movement Therapy dedicate their time to creating safe spaces for patients with Parkinson’s, curated specifically for developing voluntary movement habits and sparking rehabilitation. They provide opportunities to not only go through the basics of a dance class, but also to study choreography and perform, incentives that encourage participants to continue coming back to class, continue to reap the benefits of treatment, and improve their quality of life. Dance is an art form, but it has the ability to transcend the boundaries of the stage and make its way into science. Its art is inherently based in movement, in the shapes it creates, in the connection between point A and point B. Dance acting as a complementary therapy to pharmacological treatment is merely the first step in the connection between science and the arts.

References

1. Dauer, W., & Przedborski, S. (2003). Parkinson’s Disease: Mechanisms and Models. Neuron, 39(6), 889–909. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00568-3

2. Juárez Olguín, H., Calderón Guzmán, D., Hernández García, E., & Barragán Mejía, G. (2015). The role of dopamine and its dysfunction as a consequence of oxidative stress. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 2016(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/9730467

3.Luca, A., Monastero, R., Baschi, R., Cicero, C. E., Mostile, G., Davì, M., Restivo, V., Zappia, M., & Nicoletti, A. (2021). Cognitive impairment and levodopa induced dyskinesia in Parkinson’s disease: a longitudinal study from the PACOS cohort. Scientific Reports, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-79110-7

4. Malek, N. (2019). Deep Brain Stimulation in Parkinson’s Disease. Neurology India, 67(4), 968. https://doi.org/10.4103/0028-3886.266268

5. Raluca-Dana Moţ, & Bogdan Almăjan-Guţă. (2022). Dance therapy for Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review. Timisora Physical Education and Rehabilitation Journal/Timişoara Physical Education and Rehabilitation Journal, 15(28), 55–65. https://doi.org/10.2478/tperj-2022-0007

6. Jola, C., Sundstrom, M., & Mcleod, J. (2022). Benefits of dance for Parkinson’s: The music, the moves, and the company. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.%20pone.0265921

7. Carapellotti, A. M., Rodger, M., & Doumas, M. (2022). Evaluating the effects of dance on motor outcomes, non-motor outcomes, and quality of life in people living with Parkinson’s: a feasibility study. Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 8(8), 36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-022-00982-9

8. de Natale, E. R., Paulus, K. S., Aiello, E., Sanna, B., Manca, A., Sotgiu, G., Leali, P. T., & Deriu, F. (2017). Dance therapy improves motor and cognitive functions in patients with Parkinson’s disease. NeuroRehabilitation, 40(1), 141–144. https://doi.org/10.3233/nre-161399

9. Rabini, G., Meli, C., Giulia Prodomi, Speranza, C., Federica Anzini, Giulia Funghi, Pierotti, E., Saviola, F., Giorgio Giulio Fumagalli, Raffaella Di Giacopo, Maria Chiara Malaguti, Jovicich, J., Dodich, A., Papagno, C., & Luca Turella. (2024). Tango and physiotherapy interventions in Parkinson’s disease: a pilot study on efficacy outcomes on motor and cognitive skills. Scientific Reports, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-62786-6

10. Bearss, K. A., & DeSouza, J. F. X. (2021). Parkinson’s Disease Motor Symptom Progression Slowed with Multisensory Dance Learning over 3-Years: A Preliminary Longitudinal Investigation. Brain Sciences, 11(7), 895. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11070895

11. Meulenberg, C. J. W., Rehfeld, K., Jovanović, S., & Marusic, U. (2023). Unleashing the potential of dance: a neuroplasticity-based approach bridging from older adults to Parkinson’s disease patients. ProQuest, 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2023.1188855

12. Bathina, S., & Das, U. N. (2015). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and its clinical implications. Archives of Medical Science, 11(6), 1164–1178. https://doi.org/10.5114/aoms.2015.56342