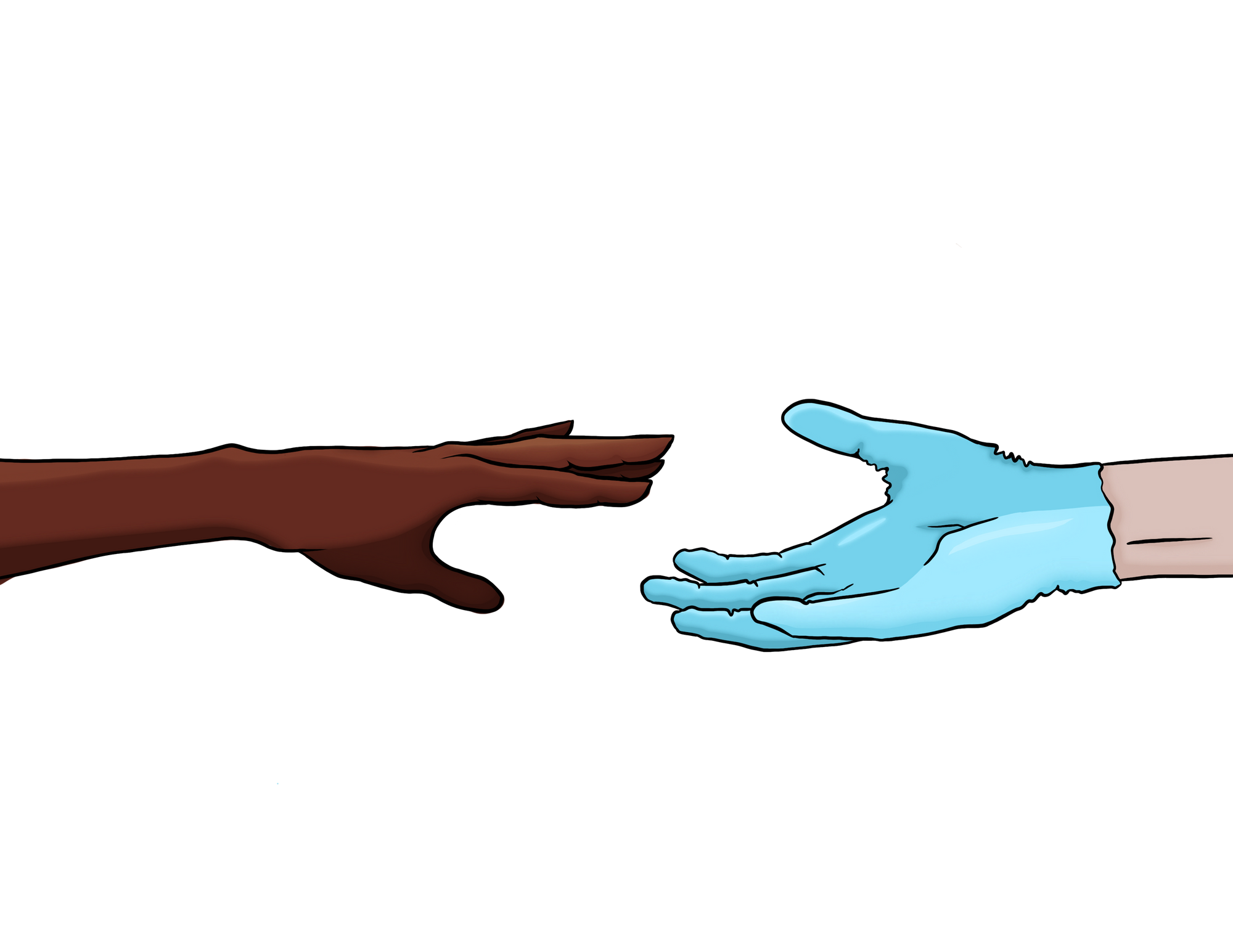

Medical research has a dark past, especially for Black Americans. Embedded in this history is the withholding of information, biases, and racism towards Black Americans. Justifications for the mistreatment of Black Americans have been around since their arrival to the Americas [1]. One justification for the racism of Black Americans is the idea of polygenism, which depicts human races as distinct species. This theory suggests that White Americans were superior to Black Americans because of differing skull shapes [1]. Polygenism and biology-based racism can explain the fear and mistrust Black Americans have toward research because of the inferiority and oppression they suffer from. Racism can create hesitancy for Black Americans contributing to medical research and feelings of subordination to communities not exposed to racism. Research mistrust refers to a study participant’s belief that their needs are subordinate to the researcher or the overall study [2]. It is a multifaceted phenomenon rooted in various historical, social, and ethical factors. It is important to note that research mistrust exists in different forms while affecting multiple communities over time. Addressing research mistrust requires a commitment to transparency, ethics, and inclusivity. Therefore, building trust with impacted communities is essential for the responsible conduct of ethics and the advancement of research.

Background

Mistrust in research is prevalent in multiple racial and ethnic minority groups, but it is most prominent among Black Americans [3]. There is an enduring history of unethical and abusive research in this community [4]. The fear research mistrust causes among Black Americans not only impacts research but also the psychology of the affected participants. The disparity Black Americans experience from information being withheld, study risks, or potentially defamatory data, causes fear within this population. When researchers practice unethically, it can lead to greater racial disparities. These disparities can derive from a lack of recognition, leading to feelings of subordination. Clinical research has a history of dehumanizing minorities, especially Black Americans, making them feel like “guinea pigs” [5]. Invalidating one’s identity can induce feelings of inferiority and worthlessness. These feelings may be associated with racial disparities in our society.

The inequitable research practices inflicted on Black Americans result in individuals losing confidence in scientific research, creating a divide between academia and society. When participants are skeptical and don’t actively contribute to the study, findings tend to be inaccurate and unreliable [6]. Researchers may feel the need to manipulate participants by leaving out certain information or lying to the target sample to obtain the conclusions they want. This creates data that is no longer representative of what occurs naturally, rather it is what the scientist wants [6].

It is no surprise that many Black Americans want nothing to do with research. Black Americans face injustice not only in research but in multiple aspects of the healthcare system, worsening this disparity [4]. Discrimination creates tension within society by allowing conflict between different groups and perpetuates injustice and inequality [6]. These inequalities amplify prejudice in society, creating a further divide between groups of people.

Prior Studies

A notorious example is the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, conducted in the United States from 1932 to 1972. The study was initiated by the U.S. Public Health Service to investigate the natural progression of untreated syphilis in Black American men [7]. The researchers aimed to observe the long-term effects of the disease without providing the participants with proper treatment. The study consisted of 600 Black American men, of which 399 had contracted syphilis before the study began, and the remaining 201 were uninfected and served as a control group. The men involved in the study were mostly poor and had limited access to healthcare. The most significant ethical violation was the intentional withholding of treatment. Even though penicillin was discovered in the 1940s as an effective treatment for syphilis, the researchers did not provide the necessary treatment to the participants [8]. By not providing necessary treatments for Black Americans, they were more susceptible to disease and ill health. Because of this, Black Americans may be fearful of taking medication or seeking help for health-related issues, making this community more at risk for disease and feelings of alienation from the rest of society that does not experience racism. The participants were also not informed about the true purpose of the study. They were misled into believing that they were receiving treatment for their conditions when, in reality, they were not. On top of this, participants were not provided with information about the potential risks and benefits of their participation [8]. By withholding information, Black Americans could quickly lose trust in research since they may be skeptical about how they are being treated. Because of this, Black Americans may not want to contribute to research because of the lack of communication and fear of not knowing the full truth of how they are contributing. The issue this creates is that Black Americans may feel subordinate to other races who may have better interactions with researchers. Many participants in this study suffered severe health complications, including death, as a direct result of untreated syphilis [8]. Studies like this perpetuate the mistrust many Black Americans have toward research because of the fear that they are jeopardizing their health when contributing to science. Because of this, impacted individuals may question what is being done to prevent mistrust from something like this study from occurring again. The Tuskegee syphilis study played a pivotal role in the development of ethical guidelines for human research [9]. The establishment of Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) was created to prevent unethical studies such as Tuskegee. This study is a stark reminder of the ethical responsibilities researchers must have to respect and maintain human rights while conducting research. Violating human rights only creates further division in society, creating disparity and fear.

Another example of medical mistrust is the story of Henrietta Lacks, an African-American woman who died of cervical cancer in 1951, which exemplifies why so many Black Americans experience research mistrust. Without her knowledge or informed consent, a sample of her cancer cells was dispersed by researchers once she died [10]. Her cells, known as HeLa cells, were distributed to laboratories worldwide and became a crucial tool in various areas of biomedical research. HeLa cells significantly contributed to the polio vaccine, cancer research, and studies on cell biology [11]. Though advancements were made from Lacks’ cells, Henrietta was never informed about the use of her cells for research purposes, and her family did not learn about the use of her cells in research until years later, after Henrietta’s death, and were not given any of the immense profits from the cells [10]. Though Henrietta never seemed to face mistrust herself, the actions taken by researchers after her death contributed to Black Americans distrusting research. Since researchers were selling human body parts, people may fear the information they share with health authorities is being compromised. For the Lacks family, Henrietta’s genome was sequenced and published without her family's permission [12]. With this in mind, Black Americans can become skeptical about sharing information to providers, which could burden their health by not getting adequate care. This study raised questions about the collection and privacy of one’s health. The Henrietta Lacks case led to reforms in research ethics. In 2013, the National Institute of Health and the Lacks family reached a legal agreement. Within this agreement, the family now has access to her genetic information while providing privacy [11]. The story of Henrietta Lacks also contributed to the establishment of Institutional Review Boards, enforcing informed consent [9].

Social Dilemma

The systemic racism Black Americans face, including racism in research, exposes individuals to higher levels of stress, making them more susceptible to chronic diseases [13]. The undermining of one’s self-esteem worsens racial health and social disparities [14]. Black Americans suffering from unethical research can be inclined to higher levels of stress. Many neurological disorders, including loss of memory and cognition, are associated with stress. It is important to note that unethical research is not the leading cause of these health disparities, but it is a contributing factor that needs to be addressed.

Feelings of inferiority can also have detrimental effects on one’s health. Black Americans are less likely to seek health care because of the racism they encounter [15]. The mistrust Black Americans have, along with the fear of discrimination, exacerbates poorer health outcomes. These outcomes include higher levels of stroke, hypertension, and heart disease [15][16]. It is important to note that discrimination still exists within healthcare today, especially with microaggressions during COVID-19 [17]. The killing of George Floyd as well as the disproportionate burden of COVID-19 in communities of color compared to White Americans exemplifies that this issue still exists. With regards to COVID, Black Americans may also be skeptical about receiving the vaccine due to the rough history this community has with medical treatment, as seen in the Tuskegee study. This ultimately leads to unequal burdens between races during COVID because Black Americans may be fearful of obtaining proper treatment compared to White Americans who did not suffer from racism [17].

It is also important to note the lack of minority participation in clinical research. In 2007, Black Americans only represented in about 15% of clinical research studies [18]. This can cause minorities, specifically Black Americans, to lack confidence in providers when making decisions about their health, leading to fewer Black Americans seeking health care, and having higher rates of morbidity and mortality compared to White Americans [16].

Regarding healthcare in the United States, professionals may hold unconscious biases towards certain races [15]. These biases, known as implicit biases, tend to associate positive attitudes toward Whites and negative attitudes toward people of color. The Implicit Association Test measures implicit bias, and individuals who take the IAT are given a score that is representative of their bias, with higher scores meaning higher levels of implicit bias. For healthcare workers, a literature analysis of studies on implicit bias found that a majority had some level of implicit bias [15]. In a study examining the well-being of patients with spinal cord injuries cared for by physicians with high IAT scores, it was seen that they had lower social integration and higher levels of depression. This can be correlated to the racism Black Americans suffer from [19]. This study demonstrates the marginalization Black Americans are burdened with, and how ongoing discrimination can inflict poor health outcomes.

What Now?

To ensure the benefits of research while being respectful of human rights, it is essential to recognize and reduce mistrust in research. One effective strategy is to have complete transparency and implement informed consent [20]. Maintaining an open and truthful conversation with the participants can help mitigate any confusion or concerns they may have when contributing to research. These conversations can include sharing research goals, methodologies, and the purpose of the study. This discussion helps participants feel comfortable in a study, yielding more accurate results [20][21]. This autonomy protects participants' rights and safeguards some of the ethical concerns a study may have. Without informed consent, an individual loses their rights, and the study violates several codes of ethics. It is crucial to communicate properly and truthfully with research participants to not only achieve credible results but also to prevent disparity.

Another approach to decreasing research mistrust involves educating individuals about their rights as research participants. One of the most effective strategies to promote advances in science is education [22]. Impacted communities can learn about the value and impact of research and its role in improving society. By providing clear and accessible information, individuals can understand the basis of research which may entice them to participate. Educating individuals about the amount of progress and ethical basis research practices today can foster greater participation.

On a positive note, some researchers are aware of the discrimination Black Americans face in research and are coming up with ways to get more representation for these communities. The lack of clinical research among Black Americans contributes to the mistrust in research [18]. The Sharing History through Active Reminiscence and Photo-imagery (SHARP) program is a neuroscience-related intervention to promote Black Americans participating in research [23]. This program targeted Black Americans, studying the health and independent aging of participants' brains. What is great about this is the inclusion of Black Americans in research, allowing the population to trust and become comfortable with research. This program's emphasis on Black American research spun the negative connotations minorities may have with research into a new light. Recognizing disparities within research is one thing, but actively fighting problems in society is another. For SHARP, this was the inclusivity and success of this program [23]. Doing so allows minority communities like Black Americans to be more comfortable with research, thus fighting to end research mistrust.

References

- Harvard Library (n.d.). Confronting Anti-Black racism: Scientific racism. Harvard Library. https://library.harvard.edu/confronting-anti-black-racism/scientific-racism

- Smirnoff, M., Wilets, I., Ragin, D. F., Adams, R., Holohan, J., Rhodes, R., Winkel, G., Ricci, E. M., Clesca, C., & Richardson, L. D. (2018). A paradigm for understanding trust and mistrust in medical research: The Community VOICES study. AJOB empirical bioethics, 9(1), 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/23294515.2018.1432718

- Knopf A. S., Krombach P., Katz A. J., Baker R., & Zimet G. (2021). Measuring research mistrust in adolescents and adults: Validity and reliability of an adapted version of the Group-Based Medical Mistrust Scale. PLoS ONE, 16(1). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245783

- Gamble V. N. (1997). Under the shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and health care. American Journal of Public Health, 87(11), 1773–1778. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.87.11.1773

- Scharff, D. P., Mathews, K. J., Jackson, P., Hoffsuemmer, J., Martin, E., & Edwards, D. (2010). More than Tuskegee: understanding mistrust about research participation. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 21(3), 879–897. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.0.0323

- American Psychological Association (2016). Stress in America: The impact of discrimination. Stress in America™ Survey.

- White R. M. (2000). Unraveling the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis. Archives of Internal Medicine, 160(5), 585–598. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.160.5.585

- Tobin M. J. (2022). Fiftieth Anniversary of Uncovering the Tuskegee Syphilis Study: The Story and Timeless Lessons. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 205(10), 1145–1158. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202201-0136SO

- White R. M. (2005). Misinformation and misbeliefs in the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis fuel mistrust in the healthcare system. Journal of the National Medical Association, 97(11), 1566–1573.

- Khan F. A. (2011). The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. The Journal of IMA, 43(2), 93–94. https://doi.org/10.5915/43-2-8609

- Grady C. (2015). Institutional Review Boards: Purpose and Challenges. Chest, 148(5), 1148–1155. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.15-0706

- Svalastog, A. L., & Martinelli, L. (2013). Representing life as opposed to being: the bio-objectification process of the HeLa cells and its relation to personalized medicine. Croatian Medical Journal, 54(4), 397–402. https://doi.org/10.3325/cmj.2013.54.397

- Banaji, M.R., Fiske, S.T. & Massey, D.S. (2021). Systemic racism: individuals and interactions, institutions and society. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-021-00349-3

- Bravemen, P. A., Arkin, E., Proctor, D., Kauh, T., & Holm, N. (2022). Systemic and structural racism: Definitions, examples, health damages, and approaches to dismantling. Health Affairs, 41(2). https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01394

- Theard, M. A. (2021). An Examination of History for Promoting Diversity in Neuroscience. Current Anesthesiology Reports, 11(3), 202–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40140-021-00464-3

- National Academies Press (2017). The State of Health Disparities in the United States. Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK425844/

- Togioka, B. M., Duvivier, D., Young, E. (2023). Diversity and discrimination in Healthcare. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK568721/

- Fisher, J. A., & Kalbaugh, C. A. (2011). Challenging assumptions about minority participation in US clinical research. American Journal of Public Health, 101(12), 2217–2222. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300279

- Hausmann, L. R., Myaskovsky, L., Niyonkuru, C., Oyster, M. L., Switzer, G. E., Burkitt, K. H., Fine, M. J., Gao, S., & Boninger, M. L. (2015). Examining implicit bias of physicians who care for individuals with spinal cord injury: A pilot study and future directions. The journal of spinal cord medicine, 38(1), 102–110. https://doi.org/10.1179/2045772313Y.0000000184

- Ioannidis J. P. (2005). Why most published research findings are false. PLoS Medicine, 2(8), e124. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124

- Nuijten, M. B., Hartgerink, C. H., van Assen, M. A., Epskamp, S., & Wicherts, J. M. (2016). The prevalence of statistical reporting errors in psychology (1985-2013). Behavior Research Methods, 48(4), 1205–1226. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-015-0664-2

- Hahn, R. A., & Truman, B. I. (2015). Education Improves Public Health and Promotes Health Equity. International Journal of Health Services, 45(4), 657–678. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020731415585986

- Croff, R. L., Witter Iv, P., Walker, M. L., Francois, E., Quinn, C., Riley, T. C., Sharma, N. F., & Kaye, J. A. (2019). Things Are Changing so Fast: Integrative Technology for Preserving Cognitive Health and Community History. The Gerontologist, 59(1), 147–157. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gny069